Abortion holds a unique place in the realm of American public opinion.

While views on issues like same-sex marriage and marijuana legalization have shifted dramatically over the last ten years, people tend to hold on to their positions on abortion. In my upcoming book, 20 Myths about Religion and Politics in America, I spend a chapter explaining how abortion opinion is basically unchanged over the last four decades.

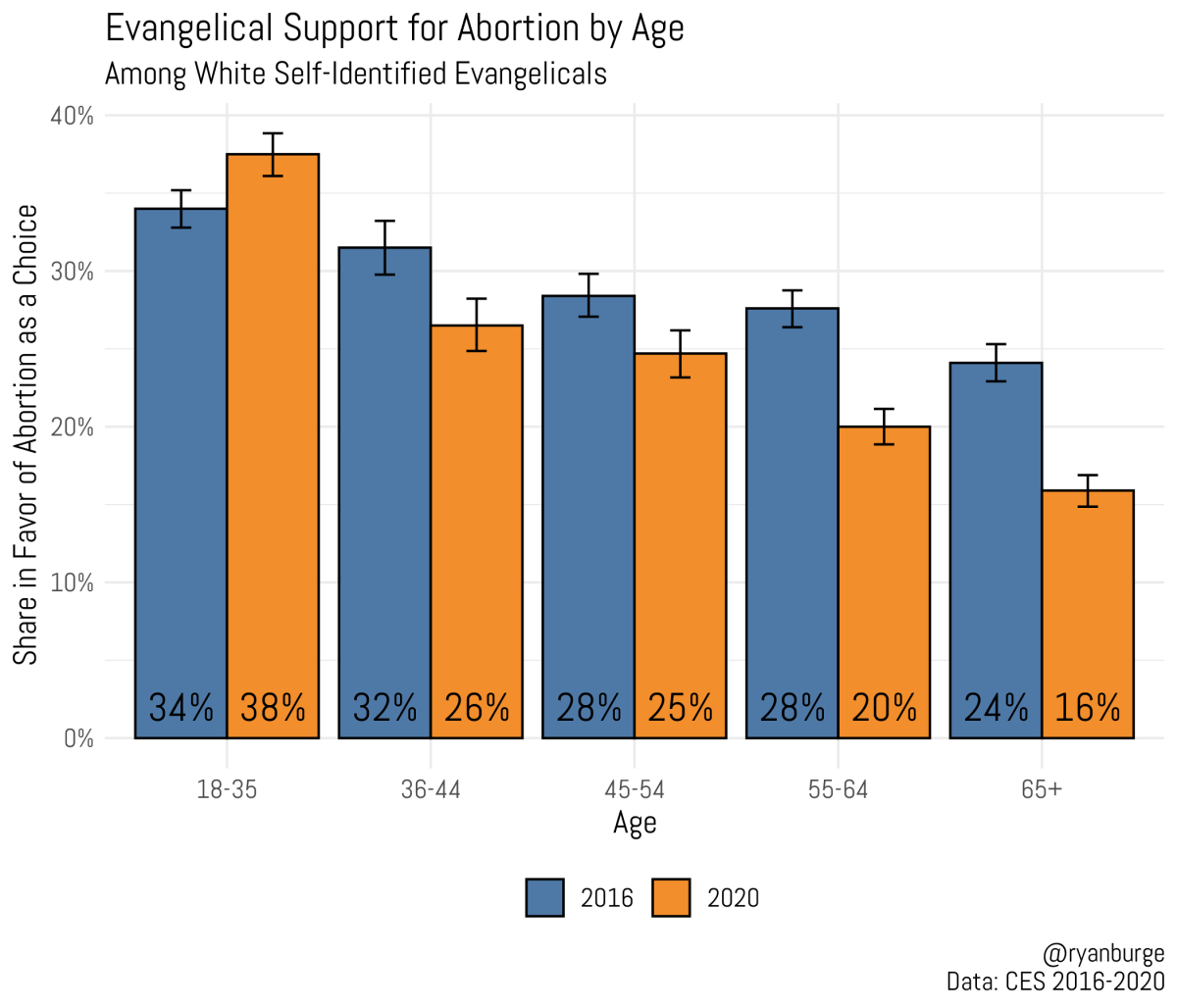

Evangelicals have been the religious group with the strongest views against abortion, and across generations, they’ve held to their pro-life stances. As recently as 2016, the age gap between younger and older generations on the issue was small and substantially insignificant.

But data from 2020 has begun to show a different trend. Younger white evangelicals have become more permissive of abortion, while older ones have moved in the opposite direction.

When survey participants were asked about abortion rights—whether women should always be allowed to obtain an abortion as a matter of choice—overall support was predictably low in 2016. Just a third of those 35 and younger were in favor. In older groups, fewer and fewer evangelicals were in support. Among white evangelicals of retirement age, less than a quarter were in favor. There was about a 10-percentage-point gap between the youngest and oldest evangelicals on the issue of abortion.

The leader of the Christian Right tells how political activism has affected him.Shedding his earlier opposition to political involvement, Jerry Falwell helped found Moral Majority in 1979. The group was organized to oppose abortion and to support traditional family values, a strong national defense, and the State of Israel.Moral Majority enabled fundamentalists to join forces with those from other religious traditions in addressing social and moral issues. Falwell says Catholics make up the largest constituency in Moral Majority, accounting for some 30 percent of its adherents. The organization also includes evangelicals, Jews, and Mormons.Last month, Falwell announced the formation of Liberty Federation, an umbrella organization that will address a broader range of public policy issues (CT, Feb. 7, 1986, p. 60). Among other issues, the organization will speak out on the strategic defense initiative, the spread of communism, and American foreign policy toward South Africa and the Philippines. Moral Majority is functioning as a subsidiary of Liberty Federation. Another subsidiary, Liberty Alliance, operates as the educational and political lobbying arm of Liberty Federation.CHRISTIANITY TODAY asked Falwell to assess the Religious Right in 1986. He also outlines his goals for the future, and tells how he has changed after seven years of political activism.Has the New Right’s political power crested, or will it continue to grow?The New Right has been very successful, and its influence is growing rapidly. There is a perception across the country that with Ronald Reagan in the White House, the moral issues are on the front burner, the country is moving to the Right, and we have won the battle.However, most people in the New Right would tell you they are having difficulty raising funds. That is true for two reasons. First, so many more organizations are raising funds out of the same pool. Second, the perception of safety, which our success has created, hurts fund-raising efforts. You don’t do well in fund raising unless you are in trouble.Organizations in the political Right are realizing that there are X number of people interested in supporting conservative causes, and they are all asking those same people for money. One of my friends receives at least 30 letters a day from political and conservative organizations. The number of organizations needing money is growing faster than the head count of conservative supporters. So some of these organizations are going to die out.But these factors have not affected the Christian Right. Our supporters back us out of a spiritual motivation, rather than political motivation. Our budget is 0 million—the largest ever. Our supporters are giving continuously, regardless of who is in the White House.The New Right has had a positive influence on the Christian Right. They have educated us on many of the issues, giving us political savvy in a hurry. And groups like Moral Majority have spawned hundreds of groups of conservative Christians who are now registered voters. They are speaking to the issues, and they are politically involved. The next step for us is challenging our people to run for office. We probably have 90 to 100 running this year.Your statements last fall opposing economic sanctions against South Africa raised the ire of many Americans, including religious leaders. Isn’t this a problem that has no simple theological answer?I don’t know any reasonable Christian who supports apartheid. So we begin from a point of agreement. But there is tremendous diversity on how to solve the problem. I have fundamentalist friends who disagree with my position on South Africa.I want to see every one of the 30 million residents of South Africa participating in the political process there. And I want to see it happen as quickly as possible. But I don’t want South Africa to go the route of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Angola. When colonialism became history in Africa and Europeans moved out instantly, bloodbaths occurred. The citizens of those countries had not had time to develop the expertise to operate a fair and reasonable government.The gradual move toward reform that South African President P. W. Botha is committed to will eventually bring a participatory government. It will bring an end to apartheid, and provide prosperity without bloodshed.Now, the African National Congress (ANC) and its arm inside the country, the United Democratic Front, are advocating violence. Half of the 800 people who have died have been blacks killed by blacks. There has been brutality, and you can’t excuse all the conduct of the South African government any more than you can the ANC.Change can take place. But intervention from outside—from the Soviets or the United States—will create havoc. We need to use economic pressure and a lot of restraint to give them time to do in a few years what it took America 170 years to accomplish.Your stands on political matters give rise to criticism from both the Right and the Left. How do you live with that kind of tension?I have a relative position of safety as pastor of Thomas Road Baptist Church, in Lynchburg, Virginia. We have 21,000 members who have grown up with me since the inception of the church 30 years ago. They know where I’m coming from. They have seen my views develop.Many of them were here when we were a part of the segregated South and had no black members. They were here when our first black member was baptized. They saw our philosophy change, and they saw our commitment to noninvolvement in political issues reversed. They were here long enough to hear the rationale and to see that change is not always bad.They see the weeks and weeks of information and experience that lead up to the public positions I take. As a result, no matter what may be printed in the newspapers, when I come home I have no reaction to calm down. And with no intention of ever running for political office, I don’t have to worry about opinion polls.When you espouse a position that you know will be criticized, are you prepared to respond to your opponents?As a younger preacher, I was far more sensitive to public opinion and criticism. There are two college professors who for 15 or 20 years have taped every message I have preached. They try to find some contradiction or ethnic bias or something. Every time they think they find something, they run to the Washington Post. There were days when I responded to them. But one day I realized that no matter who said what, it didn’t hurt me. My response to this garbage did me far more damage than what my critics said or did to me. So I stopped responding long ago. I operate totally on offense now.Criticism can help keep us accountable. Who carries out that function in your life?First, I am accountable to God. Next, I am accountable to a local congregation. As a pastor, I can’t have any scandals. And I can’t have a financial debacle because my congregation must have confidence in me. Third, as an organization, we are accountable to our donors. We are audited by an outside accounting firm every year. All of our donors have access to our financial statements.How has your role changed since you founded Moral Majority?Before Moral Majority was formed, I had more freedom to express my opinions. Since then, I’ve had to gradually pull in the ropes and be very cautious on making statements until I’ve weighed the impact on our own camp. The South African debate is probably the most volatile one we have been involved in because there are really good people on both sides of the issue.I’ve had to pull in my tendency to shoot from the hip. I’ve also had to learn that I can’t talk to anybody outside my own family about sensitive subjects, because my comments invariably appear in print. That’s a hard lesson for a very public, extroverted person like myself.In Lynchburg, I can stop at a hot-dog joint and talk with the guys I went to high school with. That doesn’t mean I don’t have detractors here. I do. But in this town I’m just Jerry.It’s totally different when I leave Lynchburg. My high visibility has made me become what I don’t like to be: a private person outside of my home town. That is the most painful consequence of what I do.Liberty University is a special concern of yours. What are your hopes and dreams for that school?Liberty University is my way of carrying out the dream and vision God has given me. That vision is to give the gospel to the world in my generation. Television and radio are effective; the local church here is effective; our speaking tours are effective. But my hope for making an impact on the world with this generation and generations to come is to train young people in the things that are vital to the cause of world evangelization.Now in our fifteenth year, we have 6,900 students. We have 75 majors, and we are fully accredited. Our master’s program is in place, and our doctoral program begins this fall. We’re also planning to start a law school. When you include our elementary and high school, we have 8,500 students. We have a dream of 50,000 students shortly after the first of the century.There are several areas where Liberty University can reverse the trends that have corrupted society. We have trained 1,000 preachers. We have also trained journalists. We have a large business major, and a large education major. Our students who major in political science are required to work as interns in Washington for senators and congressmen. One of our graduates is running for Congress this fall. One day we will be doing what Harvard has done. We’ll have hundreds of our graduates running for office.How is God moving you further along the ministry path he has set for you?At age 52, my spiritual growth is as important as it was 34 years ago when I became a Christian. The study of the Word of God, my personal relationship with God, and my time in fellowship and prayer are as vital, if not more so, now as in the past.I read a lot—not only the Bible and books about the Bible and men and women of God—but also books like Iacocca and Losing Ground. I try to read all the best sellers that are coming out so the world doesn’t walk past us. I probably read two books a week. I have to make some sacrifices in order to find the time to do that. I’m trying to improve myself. I’m trying to learn. I’m trying as hard to grow now as I did 30 years ago so that I am capable of leading the people that God has put under my ministry.What would you like your legacy to be?I’d like to be remembered as a good husband, father, and pastor. That is my first calling. I’ve got three children in school. Two of them are in college, and one is in law school. We do everything together. I may fail in a lot of areas, but, God willing, it won’t be at home.Likewise, as pastor of Thomas Road Baptist Church, I’m always here on Sunday morning, Sunday night, and Wednesday morning. I won’t miss two Wednesday nights a year. And I don’t miss any Sunday mornings.NORTH AMERICAN SCENEPROLIFE DEMONSTRATION36,000 March in WashingtonThe annual March for Life brought an estimated 36,000 people to Washington, D.C., last month to protest legalized abortion. The demonstration marked the thirteenth anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade ruling that made abortion legal in the United States.Marchers gathered on the Ellipse behind the White House where they heard an address by President Reagan via a telephone and loudspeaker hookup. “We will continue to work together with members of Congress to overturn the tragedy of Roe v. Wade,” Reagan said.The demonstrators also heard from members of Congress, including U.S. Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) and U.S. Rep. Jack Kemp (R-N.Y.). “The success of this movement is assured,” Kemp said, “not only because it’s predicated on those Judeo-Christian values upon which America was founded, but because it is pro-people.”The demonstrators marched to the Supreme Court building and the Capitol, where they lobbied members of Congress. Ten persons were arrested for demonstrating at the Supreme Court, and 31 others were arrested for protests at two Washington, D.C., abortion clinics.Proponents of legalized abortion used the occasion to criticize the prolife movement. Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization for Women, said her group is planning a major march in Washington this spring in support of artificial contraception and legalized abortion.UNIFICATION CHURCHVoices of DissentTwo newsletters are calling for change in the Unification Church, the cult headed by Korean religious leader Sun Myung Moon.The newsletters, published by members of the Unification Church, call for greater freedom in personal lifestyles, more democratic participation by members, and doctrinal reform. One of the newsletters, The Round Table, was started last year by graduates of the Unification Theological Seminary in Barrytown, New York. The other, called Our Network, was begun in 1984 to support Moonies who are moving out of the cult’s mainstream.Our Network editor Aquacena Lopez said most of Moon’s followers live outside the communal centers that serve as bases for the Unification Church’s missionary work. She said those followers feel rejected by Moon’s organization.David Doose, an editor of The Round Table, said many members oppose the authoritarian style of Unification leaders from Eastern nations, primarily Korea. Another Round Table editor said many Unificationists want Moon’s organization to stress a stronger relationship to historic Christianity.Doose said a Unification Church newsletter called The Pyramid is being published in part to counter the impact of The Round Table. However, Pyramid editor Dan Stringer said his newsletter is “only meant to articulate the faith of many members.” Stringer, a member of a Unification anti-Communist organization called CAUSA, said many of the dissenters “have not reconciled themselves to authority.… [They] leave themselves little choice but to move on and go beyond the Unification Church.”TRENDSPoor Do Worse in 1985Demands for emergency food and shelter rose sharply last year in most of the 25 cities surveyed by the United States Conference of Mayors.A report prepared by the organization says the demand for emergency food rose an average of 28 percent during 1985. Officials in 66 percent of the cities said the demand is so great that they must turn people away from their emergency food assistance programs.Demands for shelter increased in 90 percent of the cities surveyed, staying the same in the remaining cities. Officials in most of the 25 cities said poverty levels remained the same or increased during 1985.In a separate study, the National Urban League reported that economic and social gaps between blacks and whites in America widened significantly last year. In its annual report, the civil rights organization said income and educational attainment among blacks has declined in relation to whites. Poverty, youth unemployment, and single-parent families among black Americans increased.National Urban League president John E. Jacob said government figures show that in 1984, the latest year for which figures are available, the median income of blacks dropped to 56 percent of the white median income. In 1970, the figure was 62 percent.PEOPLE AND EVENTSBriefly NotedDamaged: By fire, the platform area of Chicago’s historic Moody Church. Fire destroyed the church’s pulpit, a grand piano, parts of a pipe organ, and the public address system. No one was injured in the blaze. Authorities said an intruder ransacked two church offices and then apparently ignited the fire after pouring a flammable liquid around the pulpit. Damage to the church was estimated at 0,000.Appointed: To chair the board of World Vision International, Roberta Hestenes, director of the Christian Formation and Discipleship Program at Fuller Theological Seminary. An ordained Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) minister, Hestenes is the first woman to head the World Vision board in the agency’s 35-year history.Died: Former Wheaton (Ill.) College registrar Enock C. Dyrness, 83, on January 15, in Walnut Creek, California. A 1923 Wheaton College graduate, Dyrness served on the college’s faculty and administration for more than 40 years.Presented: To Navajo official Edward T. Begay, a copy of the first complete Bible translated into the Navajo language. The Navajo nation, representing 220,000 native Americans, first received the complete New Testament in its language in 1956. Navajo Bible Translators, with financial support from Wycliffe Bible Translators and the American Bible Society, finished the complete Navajo Bible last year.

The leader of the Christian Right tells how political activism has affected him.Shedding his earlier opposition to political involvement, Jerry Falwell helped found Moral Majority in 1979. The group was organized to oppose abortion and to support traditional family values, a strong national defense, and the State of Israel.Moral Majority enabled fundamentalists to join forces with those from other religious traditions in addressing social and moral issues. Falwell says Catholics make up the largest constituency in Moral Majority, accounting for some 30 percent of its adherents. The organization also includes evangelicals, Jews, and Mormons.Last month, Falwell announced the formation of Liberty Federation, an umbrella organization that will address a broader range of public policy issues (CT, Feb. 7, 1986, p. 60). Among other issues, the organization will speak out on the strategic defense initiative, the spread of communism, and American foreign policy toward South Africa and the Philippines. Moral Majority is functioning as a subsidiary of Liberty Federation. Another subsidiary, Liberty Alliance, operates as the educational and political lobbying arm of Liberty Federation.CHRISTIANITY TODAY asked Falwell to assess the Religious Right in 1986. He also outlines his goals for the future, and tells how he has changed after seven years of political activism.Has the New Right’s political power crested, or will it continue to grow?The New Right has been very successful, and its influence is growing rapidly. There is a perception across the country that with Ronald Reagan in the White House, the moral issues are on the front burner, the country is moving to the Right, and we have won the battle.However, most people in the New Right would tell you they are having difficulty raising funds. That is true for two reasons. First, so many more organizations are raising funds out of the same pool. Second, the perception of safety, which our success has created, hurts fund-raising efforts. You don’t do well in fund raising unless you are in trouble.Organizations in the political Right are realizing that there are X number of people interested in supporting conservative causes, and they are all asking those same people for money. One of my friends receives at least 30 letters a day from political and conservative organizations. The number of organizations needing money is growing faster than the head count of conservative supporters. So some of these organizations are going to die out.But these factors have not affected the Christian Right. Our supporters back us out of a spiritual motivation, rather than political motivation. Our budget is 0 million—the largest ever. Our supporters are giving continuously, regardless of who is in the White House.The New Right has had a positive influence on the Christian Right. They have educated us on many of the issues, giving us political savvy in a hurry. And groups like Moral Majority have spawned hundreds of groups of conservative Christians who are now registered voters. They are speaking to the issues, and they are politically involved. The next step for us is challenging our people to run for office. We probably have 90 to 100 running this year.Your statements last fall opposing economic sanctions against South Africa raised the ire of many Americans, including religious leaders. Isn’t this a problem that has no simple theological answer?I don’t know any reasonable Christian who supports apartheid. So we begin from a point of agreement. But there is tremendous diversity on how to solve the problem. I have fundamentalist friends who disagree with my position on South Africa.I want to see every one of the 30 million residents of South Africa participating in the political process there. And I want to see it happen as quickly as possible. But I don’t want South Africa to go the route of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Angola. When colonialism became history in Africa and Europeans moved out instantly, bloodbaths occurred. The citizens of those countries had not had time to develop the expertise to operate a fair and reasonable government.The gradual move toward reform that South African President P. W. Botha is committed to will eventually bring a participatory government. It will bring an end to apartheid, and provide prosperity without bloodshed.Now, the African National Congress (ANC) and its arm inside the country, the United Democratic Front, are advocating violence. Half of the 800 people who have died have been blacks killed by blacks. There has been brutality, and you can’t excuse all the conduct of the South African government any more than you can the ANC.Change can take place. But intervention from outside—from the Soviets or the United States—will create havoc. We need to use economic pressure and a lot of restraint to give them time to do in a few years what it took America 170 years to accomplish.Your stands on political matters give rise to criticism from both the Right and the Left. How do you live with that kind of tension?I have a relative position of safety as pastor of Thomas Road Baptist Church, in Lynchburg, Virginia. We have 21,000 members who have grown up with me since the inception of the church 30 years ago. They know where I’m coming from. They have seen my views develop.Many of them were here when we were a part of the segregated South and had no black members. They were here when our first black member was baptized. They saw our philosophy change, and they saw our commitment to noninvolvement in political issues reversed. They were here long enough to hear the rationale and to see that change is not always bad.They see the weeks and weeks of information and experience that lead up to the public positions I take. As a result, no matter what may be printed in the newspapers, when I come home I have no reaction to calm down. And with no intention of ever running for political office, I don’t have to worry about opinion polls.When you espouse a position that you know will be criticized, are you prepared to respond to your opponents?As a younger preacher, I was far more sensitive to public opinion and criticism. There are two college professors who for 15 or 20 years have taped every message I have preached. They try to find some contradiction or ethnic bias or something. Every time they think they find something, they run to the Washington Post. There were days when I responded to them. But one day I realized that no matter who said what, it didn’t hurt me. My response to this garbage did me far more damage than what my critics said or did to me. So I stopped responding long ago. I operate totally on offense now.Criticism can help keep us accountable. Who carries out that function in your life?First, I am accountable to God. Next, I am accountable to a local congregation. As a pastor, I can’t have any scandals. And I can’t have a financial debacle because my congregation must have confidence in me. Third, as an organization, we are accountable to our donors. We are audited by an outside accounting firm every year. All of our donors have access to our financial statements.How has your role changed since you founded Moral Majority?Before Moral Majority was formed, I had more freedom to express my opinions. Since then, I’ve had to gradually pull in the ropes and be very cautious on making statements until I’ve weighed the impact on our own camp. The South African debate is probably the most volatile one we have been involved in because there are really good people on both sides of the issue.I’ve had to pull in my tendency to shoot from the hip. I’ve also had to learn that I can’t talk to anybody outside my own family about sensitive subjects, because my comments invariably appear in print. That’s a hard lesson for a very public, extroverted person like myself.In Lynchburg, I can stop at a hot-dog joint and talk with the guys I went to high school with. That doesn’t mean I don’t have detractors here. I do. But in this town I’m just Jerry.It’s totally different when I leave Lynchburg. My high visibility has made me become what I don’t like to be: a private person outside of my home town. That is the most painful consequence of what I do.Liberty University is a special concern of yours. What are your hopes and dreams for that school?Liberty University is my way of carrying out the dream and vision God has given me. That vision is to give the gospel to the world in my generation. Television and radio are effective; the local church here is effective; our speaking tours are effective. But my hope for making an impact on the world with this generation and generations to come is to train young people in the things that are vital to the cause of world evangelization.Now in our fifteenth year, we have 6,900 students. We have 75 majors, and we are fully accredited. Our master’s program is in place, and our doctoral program begins this fall. We’re also planning to start a law school. When you include our elementary and high school, we have 8,500 students. We have a dream of 50,000 students shortly after the first of the century.There are several areas where Liberty University can reverse the trends that have corrupted society. We have trained 1,000 preachers. We have also trained journalists. We have a large business major, and a large education major. Our students who major in political science are required to work as interns in Washington for senators and congressmen. One of our graduates is running for Congress this fall. One day we will be doing what Harvard has done. We’ll have hundreds of our graduates running for office.How is God moving you further along the ministry path he has set for you?At age 52, my spiritual growth is as important as it was 34 years ago when I became a Christian. The study of the Word of God, my personal relationship with God, and my time in fellowship and prayer are as vital, if not more so, now as in the past.I read a lot—not only the Bible and books about the Bible and men and women of God—but also books like Iacocca and Losing Ground. I try to read all the best sellers that are coming out so the world doesn’t walk past us. I probably read two books a week. I have to make some sacrifices in order to find the time to do that. I’m trying to improve myself. I’m trying to learn. I’m trying as hard to grow now as I did 30 years ago so that I am capable of leading the people that God has put under my ministry.What would you like your legacy to be?I’d like to be remembered as a good husband, father, and pastor. That is my first calling. I’ve got three children in school. Two of them are in college, and one is in law school. We do everything together. I may fail in a lot of areas, but, God willing, it won’t be at home.Likewise, as pastor of Thomas Road Baptist Church, I’m always here on Sunday morning, Sunday night, and Wednesday morning. I won’t miss two Wednesday nights a year. And I don’t miss any Sunday mornings.NORTH AMERICAN SCENEPROLIFE DEMONSTRATION36,000 March in WashingtonThe annual March for Life brought an estimated 36,000 people to Washington, D.C., last month to protest legalized abortion. The demonstration marked the thirteenth anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade ruling that made abortion legal in the United States.Marchers gathered on the Ellipse behind the White House where they heard an address by President Reagan via a telephone and loudspeaker hookup. “We will continue to work together with members of Congress to overturn the tragedy of Roe v. Wade,” Reagan said.The demonstrators also heard from members of Congress, including U.S. Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) and U.S. Rep. Jack Kemp (R-N.Y.). “The success of this movement is assured,” Kemp said, “not only because it’s predicated on those Judeo-Christian values upon which America was founded, but because it is pro-people.”The demonstrators marched to the Supreme Court building and the Capitol, where they lobbied members of Congress. Ten persons were arrested for demonstrating at the Supreme Court, and 31 others were arrested for protests at two Washington, D.C., abortion clinics.Proponents of legalized abortion used the occasion to criticize the prolife movement. Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization for Women, said her group is planning a major march in Washington this spring in support of artificial contraception and legalized abortion.UNIFICATION CHURCHVoices of DissentTwo newsletters are calling for change in the Unification Church, the cult headed by Korean religious leader Sun Myung Moon.The newsletters, published by members of the Unification Church, call for greater freedom in personal lifestyles, more democratic participation by members, and doctrinal reform. One of the newsletters, The Round Table, was started last year by graduates of the Unification Theological Seminary in Barrytown, New York. The other, called Our Network, was begun in 1984 to support Moonies who are moving out of the cult’s mainstream.Our Network editor Aquacena Lopez said most of Moon’s followers live outside the communal centers that serve as bases for the Unification Church’s missionary work. She said those followers feel rejected by Moon’s organization.David Doose, an editor of The Round Table, said many members oppose the authoritarian style of Unification leaders from Eastern nations, primarily Korea. Another Round Table editor said many Unificationists want Moon’s organization to stress a stronger relationship to historic Christianity.Doose said a Unification Church newsletter called The Pyramid is being published in part to counter the impact of The Round Table. However, Pyramid editor Dan Stringer said his newsletter is “only meant to articulate the faith of many members.” Stringer, a member of a Unification anti-Communist organization called CAUSA, said many of the dissenters “have not reconciled themselves to authority.… [They] leave themselves little choice but to move on and go beyond the Unification Church.”TRENDSPoor Do Worse in 1985Demands for emergency food and shelter rose sharply last year in most of the 25 cities surveyed by the United States Conference of Mayors.A report prepared by the organization says the demand for emergency food rose an average of 28 percent during 1985. Officials in 66 percent of the cities said the demand is so great that they must turn people away from their emergency food assistance programs.Demands for shelter increased in 90 percent of the cities surveyed, staying the same in the remaining cities. Officials in most of the 25 cities said poverty levels remained the same or increased during 1985.In a separate study, the National Urban League reported that economic and social gaps between blacks and whites in America widened significantly last year. In its annual report, the civil rights organization said income and educational attainment among blacks has declined in relation to whites. Poverty, youth unemployment, and single-parent families among black Americans increased.National Urban League president John E. Jacob said government figures show that in 1984, the latest year for which figures are available, the median income of blacks dropped to 56 percent of the white median income. In 1970, the figure was 62 percent.PEOPLE AND EVENTSBriefly NotedDamaged: By fire, the platform area of Chicago’s historic Moody Church. Fire destroyed the church’s pulpit, a grand piano, parts of a pipe organ, and the public address system. No one was injured in the blaze. Authorities said an intruder ransacked two church offices and then apparently ignited the fire after pouring a flammable liquid around the pulpit. Damage to the church was estimated at 0,000.Appointed: To chair the board of World Vision International, Roberta Hestenes, director of the Christian Formation and Discipleship Program at Fuller Theological Seminary. An ordained Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) minister, Hestenes is the first woman to head the World Vision board in the agency’s 35-year history.Died: Former Wheaton (Ill.) College registrar Enock C. Dyrness, 83, on January 15, in Walnut Creek, California. A 1923 Wheaton College graduate, Dyrness served on the college’s faculty and administration for more than 40 years.Presented: To Navajo official Edward T. Begay, a copy of the first complete Bible translated into the Navajo language. The Navajo nation, representing 220,000 native Americans, first received the complete New Testament in its language in 1956. Navajo Bible Translators, with financial support from Wycliffe Bible Translators and the American Bible Society, finished the complete Navajo Bible last year.By 2020, support for abortion rights dropped among every age group but the very youngest.

Thirty-eight percent of them said that they favored abortion on demand—a four-point increase in four years. But among older evangelicals, support dropped significantly. In 2020, just 16 percent of the oldest white evangelicals were in favor, a drop of eight points in just four years. The age gap doubled in the four-year span, now up to 22 percentage points.

This age gap is persistent across a number of questions about abortion.

Respondents were asked if they favored allowing private employers to decline coverage for abortion in their insurance. Support for the policy has been robust among white evangelicals both in 2016 and 2020, never dropping below 60 percent among any age group.

However, the age gap has also grown. In 2016, there was almost no variation to this question based on age. Evangelicals born in the 1950s became even more supportive of the policy in 2020, a jump of nearly 10 points, while support from younger evangelicals dropped nearly as much. In 2016, about 73 percent of white evangelicals born in 1990 were in favor—it was 64 percent by 2020.

Representatives of the evangelical, charismatic, and Anglo-Catholic streams find unity in spiritual renewal.

Last month, the Episcopal Church installed a new presiding bishop who will set a course for the 2.8 million-member denomination through the rest of this century. Leading evangelicals, who hope to influence the church’s course, met the week before Edmond L. Browning was installed as presiding bishop. The renewal leaders emerged with a statement of united purpose, inviting the Episcopal Church to adhere to biblical tenets of faith and to acknowledge signs of spiritual renewal in its midst.

The purpose of the Winter Park, Florida, meeting was “to gather the evangelical constituency and give it a voice [because] evangelical witness has been underplayed and silent in our church for a long time,” according to Bishop Alden Hathaway of Pittsburgh, one of the conference organizers.

Episcopalians who desire renewal in the denomination make up a diverse group that is not always in complete agreement. It consists of church members who are charismatic, evangelical, and “Anglo-Catholic,” or high-church traditionalists. As a result of last month’s conference, 90 participants from all three streams agreed to work together for renewal “in whatever variety of worship and devotion the new life finds expression.”

They drafted a lengthy letter to the church, describing renewal in Episcopal parishes nationwide and summarizing position papers drafted at the meeting. They addressed biblical authority, salvation, preaching, apostolic witness, life in the Spirit, evangelism, and social outreach, among other topics. “We recognize that the Spirit is moving in our midst,” the letter states, “and our purpose is to move with Him.”

The conference grew out of a Chicago priest’s desire to meet with like-minded Episcopalians. John R. Throop, now in a Shaker Heights, Ohio, parish, spent two years developing the idea for the meeting. “Like so many people engaged in renewal in the Episcopal Church, I felt like I was an oddball, all on my own, and I could count on one hand the people I knew who were interested in renewal,” he said.

Throop wrote about his concern to John Rodgers. Rodgers is president of Trinity Episcopal School for Ministry, a newly accredited seminary in Ambridge, Pennsylvania, that has a clearly evangelical outlook.

Rodgers and Throop corresponded for several months, then convened a planning meeting with leaders from different aspects of the Episcopal renewal movement: Bishop Michael Marshall, an Anglo-Catholic speaker and writer based in St. Louis; Chuck Irish, of Episcopal Renewal Ministries (ERM); and Bishop Hathaway, among others. They set a date for the renewal conference without knowing it would immediately precede Browning’s installation as presiding bishop.

Of the more than 130 persons invited, 90 participated, including five bishops. Among the participants were some of the church’s best-known evangelicals: theologian J. I. Packer, evangelist John Guest, author Keith Miller, and ERM leader Everett L. (Terry) Fullam. Bishop William Frey of Colorado, one of four candidates for the office of presiding bishop last year, and several ordained women were also present.

Hathaway, who emerged as a leader, termed the meeting a “watershed.… Tremendous things were accomplished in terms of relationships that had been shaky,” he said. “A great spectrum of theological perspectives came together and began an amalgamation toward continuing fellowship and encouragement of one another.”

Said Richard Kew, executive director of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge/USA, a branch of the oldest Anglican mission society: “Catholics [are] bringing a richness to our evangelical emphasis which we needed.” At the same time, he said, “a maturing of charismatics is going on. The ones who have come through a crisis renewal experience are entering into something more edifying.” Many conference participants said they identify with all three streams.

How these newly united evangelicals, charismatics, and traditionalists will be received by church authorities—particularly Presiding Bishop Browning—is still in question. John Howe, rector of Truro Episcopal Church in Fairfax, Virginia, said the denomination’s “leadership as a whole has drifted in the direction of relativity and standardlessness. In loyalty and love, we want to say to them, ‘It’s time to come back to the basics.’ ”

Howe has seen renewal infuse the Episcopal Church over the past two decades, boosting the hopes of evangelicals who have remained committed to the denomination. When he attended Yale Divinity School in the 1960s, he said, J. I. Packer’s book Fundamentalism and the Word of God was laughed at. “Now,” he says, “renewed Episcopalians are speaking from the heart of the church.”

Browning has given little indication of what he thinks of renewal movements, but he has said he wants to hear from every wing of the denomination’s diverse membership. His installation sermon underlined compassion as “the root of Christian spirituality and mission” and “the hope of our future.… It was the discovery of Christ’s compassion in my own life that has been the foundation of my own spirituality, which draws me inevitably to my present witness.”

In Browning’s view, Christian compassion calls for practical expression in areas of social and political concern, such as care for the poor, environmental protection, and opposition to the arms build-up. For the past nine years, Browning has served as bishop of Hawaii. He is known as a liberal, but is cited for being open to all points of view. “There will be no outcasts,” he said in his installation sermon. “The hopes and convictions of all will be respected and honored.”

Browning is the Episcopal Church’s twenty-fourth presiding bishop. Some believe he will channel the church’s energies toward the social activism that characterized Presiding Bishop John Hines in the 1960s and early 1970s. Opposed to the Vietnam War and appalled by the havoc of race riots, Hines channeled millions of church dollars into social endeavors, some of which were backed by radical secular groups. Membership and giving dropped precipitously, and when the church chose Hines’s replacement in 1973, it opted for John M. Allin, a low-profile, cautious churchman. His 12-year term saw two major changes occur in the church. In 1977, women were ordained to the priesthood—a development that Allin opposed. In 1979, a new Book of Common Prayer came into use, updating the language and, some believe, the core doctrine of the historic prayer book.

Both of these developments drew some members away from the Episcopal Church and toward affiliation either with Roman Catholicism or conservative Protestantism. Within the church, scattered opposition to women priests and the new prayer book continues. In circles where renewal is occurring, however, these are not central issues. Fleming Rutledge, a woman priest who attended the Winter Park renewal conference, delivered a stirring sermon at the closing Communion service. Another priest, Carol Anderson, told conference participants about her congregation’s work among street people in New York City.

The basics of renewal, spelled out in the letter produced at the Florida conference, include an affirmation of Scripture as “completely trustworthy and sufficient.” Salvation, the conferees agreed, is a gift from God that is appropriated by “repentance, faith, and conversion of life” made possible by the Holy Spirit. The letter states that the Lord’s “actual resurrection from the dead attested his divinity, vindicated his claims, and broke the power of sin and death once for all.”

The letter says “the scriptural promises of supernatural resources to the believer are true,” and “the personal experience of the Holy Spirit quickens worship in the church.” It defines evangelism as a call to “personal commitment through repentance and faith.” Outreach and service are essential, according to the document, because “renewal will die unless [individuals and congregations] continue to move beyond themselves.”

A paragraph penned by theologian J. I. Packer concludes the document, stating, “Where Jesus Christ is known, trusted, loved, and adored; where the sinner is loved but all forms of sin are hated and renounced; where Christ’s living presence is sought and found in fellowship; and where righteousness is done—there the church is in renewal, in whatever variety of worship and devotion the new life finds expression.”

BETH SPRINGin Winter Park

Bishop Alden Hathaway of Pittsburgh

A Renewal Leader from Pittsburgh

According to theologian J. I. Packer, Bishop Alden Hathaway of Pittsburgh is being anointed as a leader in Episcopal renewal—a movement the bishop at one time thought was irrelevant.

In the 1960s, Hathaway served on the staff of a large suburban Detroit church, specializing in human-relations training and proabortion activism. Inner-city riots—the same events that galvanized liberal social action on the part of then Presiding Bishop John Hines—dashed Hathaway’s hopes for his ministry. “A lot of that liberal commitment evaporated over a period of months and years, as the suburbs retreated into themselves and the inner city became polarized. I saw there was something missing from that social-action movement. We were trying to do God’s work using man’s tools, and we concluded that the sin was in the institution, not in our own hearts.”

Hathaway left Detroit and took a job at a parish in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C. The church was split over the Vietnam War, and Hathaway’s best efforts to patch the congregation together had little effect. “I was absolutely burned out, tired of failing, tired of expending my energy and having nothing to show for it,” he said. Then a friend, Jim Hampson, got involved in what Hathaway called “this evangelical business.”

“We’d exchange sermons,” Hathaway said. “He’d write ‘heresy’ all over mine, and I’d write ‘irrelevant’ all over his. We argued and fought.” Hampson challenged Hathaway to submit his ministry and his life to Jesus Christ, but Hathaway resisted the notion. “I knew I had to do that, but it was not a happy thought at all. It was a bitter thought. With my heart I knew I had to get on my knees and confess Jesus, but with my pride I said no.”

At his church, Hathaway had a seminary intern who “preached the Bible, not Watergate.” He knew people were listening more attentively to the intern’s sermons, so he cynically decided, “Okay, you’ll get Bible stories.” He changed his preaching to conform with what he heard from the divinity student, and noticed something happening.

“I found a power and authority that was not my own. I found myself saying things that I didn’t believe or that weren’t credible, but it was touching people in a way I’d never touched them before. And it was touching me, too. It was convincing me of the power of the Word.”

Several months later, Hathaway attended a charismatic conference where he heard the preaching of Everett L. (Terry) Fullam, rector of Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church in Darien, Connecticut. “I heard Scripture being used in a different way. It all pointed to Jesus. In the confidence of that, I laid down my life and received the Holy Spirit. Nothing particularly happened, except I realized I was on the right track, that Jesus was with me. It’s been slow growth ever since then.”

In 1980, Hathaway was elected bishop of Pittsburgh, placing him in the role of overseeing a great variety of priests and parishioners. “I have a diocese with all kinds of sheep in it,” he said. “It’s not my job to sort them; it’s my job to feed them. The only thing I will not tolerate is skepticism on the [divine-human nature] of Christ. We are not a unitarian church, and I don’t buy for a minute that that is a legitimate Anglican position.”

Hathaway is unfazed by the prospect of a major leadership role in the spiritual renewal of the Episcopal Church. He took charge of sending the renewal conference’s letter to Presiding Bishop Edmond L. Browning, and offered to coordinate a meeting of conference organizers to discuss ways to cooperate in the future. “I know I’m where God wants me,” he said, “and I wouldn’t be any place else in the whole world.”

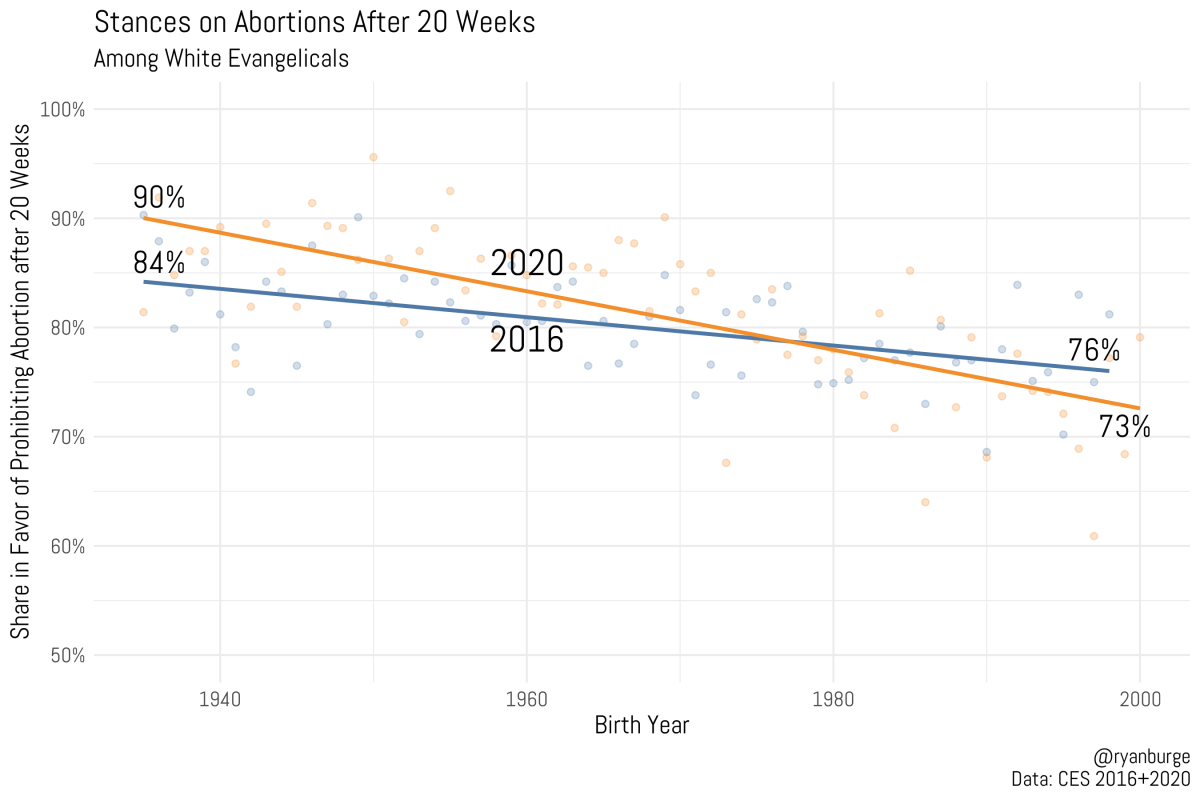

When respondents were asked about late-term abortions, the age gap persisted. In 2016, between 80 percent and 85 percent of older white evangelicals supported a ban on abortion after 20 weeks of gestation. Just four years later, support for a ban increased by about five percentage points.

Yet among evangelicals born in 1980 or later, there was less enthusiasm for a late-term abortion ban in 2020 compared to 2016. Among white evangelicals born in 1990, 77 percent were in favor in 2016, dropping to 74 percent in 2020. While the majority still believe in banning late-term abortions, the age gap is much larger in 2020 compared to 2016.

It’s not possible to say that white evangelicals actually changed their minds on abortion because the same people were not surveyed in both waves of the research. Instead, we can see that older people who identified as evangelicals were more anti-abortion in 2020 than they were in 2016, while younger white evangelicals became more in favor of abortion rights.

Why did we see so much change in just the four years between 2016 and 2020? There aren’t easy answers in the data. Younger white evangelicals, in many ways, are just as committed to Republican politics as older ones.

One potential explanation is that abortion has become less stigmatized and more openly discussed, and that can have tremendous impacts on public opinion. It’s plausible that some younger evangelicals were persuaded to moderate their stance on abortion because they had a more personal connection to the issue.

Abortion may not be as central a cause for young people overall. A 2021 New York Times article noted that “some, raised in a post-Roe world, do not feel the same urgency toward abortion as they do for other social justice causes.”

For years, pro-life evangelicals were the exception. Pro-choice advocates had worried about the “intensity gap” among young people, Slate reported, with a NARAL survey finding that pro-choice voters under 30 were half as likely as their pro-life counterparts to consider the issue of abortion “very important” in the 2016 election.

Perhaps the shifts we see among young evangelicals, and the burgeoning wave of Gen Z adults, show this distinction beginning to fade.

In a year when many evangelicals are anticipating a major milestone in the pro-life movement—the chance that the Supreme Court will overturn Roe v. Wade—it looks as if fewer young believers will celebrating alongside them.

Ryan Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public, and he tweets at @ryanburge.