The first time I saw Tim, I saw only a teenager with severe autism, slouched beside his caregiver, his body obviously tired from the pain it carried, his eyes far away.

But there was more to Tim than met the eye. His appearance in our community in 2015 would expose old divisions I didn’t even know were there—and spark a chain reaction of miracles that transformed my town and its churches.

Every two weeks during that school year, Tim and other teens with disabilities rode by bus 20 minutes from Inverell, our nearest substantial town, to Danthonia, the community in Australia where I live and teach. The teens would join our high school students for several hours. I loved watching the interaction as my students responded to their new friends and engaged them in simple activities: holding guinea pigs and rabbits, stroking cats (for however long they complied), looking at picture books, throwing a ball, and simply sprawling on the grass in the sunshine. And, of course, everyone looked forward to morning tea with chocolate chip cookies warm from the oven.

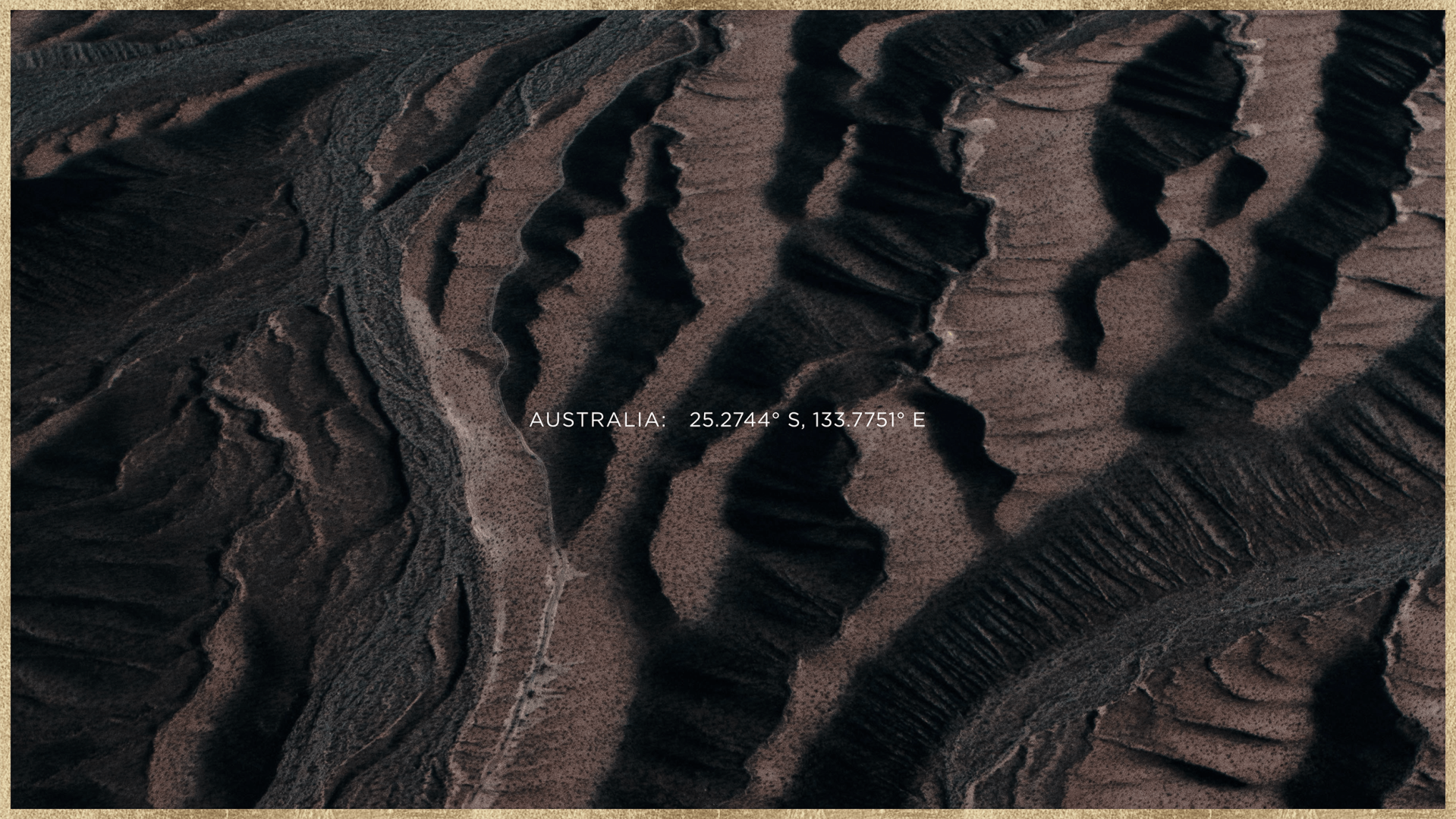

These were the kinds of scenes my husband, Chris, and I had hoped for 13 years earlier, when we moved our family from Pennsylvania to join a fledgling project in communal living in what to us was a strange land. Situated 15 miles from Inverell, in the Northern Tablelands farming district of New South Wales, Danthonia is one of more than 20 Bruderhof communities worldwide. A century ago in Germany, our founders read Acts 2 and 4 and the Sermon on the Mount and decided they could follow these teachings only by pooling their possessions.

Our spiritual moorings are in the Anabaptist tradition; the name Bruderhof dates to the Radical Reformation of the 1500s and translates literally as “place of brothers”—although Bruderhof communities have always included women, families, and singles.

The more Tim was in our life, however, the more I could see how much ground he was losing. I knew that Tim had exhibited autism from a young age and had never been able to talk. But with each visit his ability to communicate was in decline, his seizures more frequent. His protective helmet, once worn only on “bad days,” was now his constant shield.

Tim’s mother accompanied him on one of the last visits he would make to Danthonia. She told me how distraught she and her husband were becoming as they tried to provide the constant care their tall, once-strong son needed. I could only listen, and assure her of our prayers.

Around that time a friend gave me a verse, Isaiah 43:19:

See, I am doing a new thing!

Now it springs up; do you not perceive it?

I am making a way in the wilderness

and streams in the wasteland.

My friend knew I was still struggling to make this country my home and wanted to encourage me. But in the brown landscape of rural Australia, this verse only seemed to taunt me. We’d lived through two droughts, and my heart seemed mired in a wasteland of its own creation. I was unable to believe in any new thing. That’s when the Holy Spirit began to move.

Like church leaders in many towns in many parts of the world, the pastors of Inverell were in the habit of holding a monthly meeting. Tim’s father, a minister of a well-established congregation, was a regular attendee, as was a pastor from my Bruderhof church community.

The meetings typically started with devotions and prayer, then worked through a fixed agenda and announcements in a collegial but rather businesslike manner. But at the meeting in March 2015, my pastor told me, something different occurred.

One of the pastors shared about his incarcerated and estranged son. That moment of vulnerability opened the door for another and another, and through these moments of brokenness the Holy Spirit entered. This continued in the months that followed, and a space was created for pastors across denominational lines to carry each other’s burdens. A gathering that had previously felt like a chore became a time to look forward to.

At one meeting, Tim’s father asked for prayer for his son. Soon every congregation in our town was praying for Tim and his family, uniting friends and strangers. Support came in tangible ways, too. One minister and his wife, who were not part of Tim’s family’s church, volunteered as part-time caregivers for Tim so that his parents could get a break.

Yet even as this string of a common cause began to tie communities together, it was clear to everyone that Tim’s body was worn out. Despite excellent medical care and the selfless dedication of those who loved him most, Tim was ready to go home.

In October 2015, we assembled our high school students to tell them that their friend Tim had died following a short hospitalization due to complications from pneumonia. He was 15 years old. Hundreds of others from the community gathered with us at the high school gym to bid farewell to Tim with singing and tears. His helmet lay on the stage, a symbol that his body was freed from its earthly constraints. His family testified to the peace and love that had pervaded Tim’s hospital room in his final days. They credited the atmosphere to the many prayers that had lifted the burden of Tim’s illness from their shoulders and brought it to the Cross.

In the months after Tim’s death, the pastors continued to meet with renewed purpose, often over a shared meal. Among other things, they prayed for a blessing on our town, and for better collaboration with the town’s civic leadership. States in Australia are divided into local shires administered by elected councils, and the pastors wanted to be Christ’s hands and feet in the wider community by finding ways to support council members in their work.

One day, as two pastors approached a senior council official to pitch the idea for increased civic engagement, they were taken aback at the response: The council had no interest in working with the churches until they made reparation for how unwelcoming they had been toward our community when it was first established in 1999, 17 years earlier.

This was news to the clergy in the fellowship, none of whom had been in church leadership when the Bruderhof arrived. But with a little research, they learned the history: Nearly all Inverell’s churches had snubbed our community, and in some cases had actively sought to influence government decision-making against its development.

And so, on a late summer evening in early 2016, a miracle happened when a group of leaders from Inverell churches arrived at Danthonia to meet with Bruderhof members. Tim’s parents were present, and it was the first time Chris and I had seen them since their son’s funeral.

Each pastor spoke. Many shed tears as they told how they’d learned of their churches’ past coldness toward our community. They named hostility, anger, suspicion, and gossip as sins to be repented of and barriers preventing us all from working together as a body. They asked our forgiveness. Tim’s illness and death had begun to unite our town in prayer, they said. Now, unexpectedly, a new door towards unity was being opened, if our community would be willing to forgive.

It was our turn to be taken aback. My father-in-law, who had been the direct recipient of some of the early hostility, offered assurance. “Don’t worry at all, that’s water under the bridge. We’ve moved on long ago.”

“Moving on is the Australian way,” Tim’s father responded. “But it’s not Jesus’ way. Repentance is the way of Christ, and we are here to repent.”

Over the next months, follow-up meetings were held as we did the hard work of reconciliation. Our community asked for forgiveness, too: for misunderstandings and failures in communication, for the times when we chose to settle for negative assumptions instead of assuming the best of our Christian neighbors.

Because the opposition to our community had been public, the Inverell pastors wanted the repentance and forgiveness to be public as well. On a Sunday in May, we held a reconciliation service at our community hall. The room was full of people: people of faith from across the spectrum of church expressions; people who professed no particular faith but whose steadfast friendship from the outset of our community had been truly heartwarming; representatives of local government.

As the service began, Inverell’s church leaders stood at the front, before their congregants and the Bruderhof members. They stood hand in hand, heads bowed, and asked for forgiveness. The president of the ministers’ fellowship read a statement of apology, and Danthonia’s pastor responded in acceptance and offered forgiveness and our apology as well. Together, we acknowledged mutual repentance.

We stood as one body. As a testament to the unshakable bedrock of our shared faith, we spoke with one voice repeating the Apostles’ Creed, followed by the Lord’s Prayer. We ended the service by standing and singing the “Hallelujah Chorus” from Handel’s Messiah.

It was a determined declaration that we were fully restored and reconciled as brothers and sisters under the united headship of Christ, ready to get up and on with the task of building his kingdom together.

Over the following year, another miracle happened. As we reconciled, still more doors opened for our churches to work together and serve our region as one body. As ever, God’s timing was impeccable, because the year after the reconciliation our country was plunged into a record-breaking, two-year season of drought and fires. Congregations worked together as a combined whole to care for the vulnerable populations of our town. Instead of competition and division, there was cohesion and compassion.

The rains came, the drought ended, and COVID-19 arrived. I remember bringing vegetables to an elderly woman in the early days of the pandemic and nearly tripping over grocery bags and kindling on her porch as I tried to reach the doorbell. Once again, food, firewood, and friendship were distributed to those who needed it most—not from any church in particular but from “the church of the region.”

In addition, the reconciliation efforts gave birth to a beautiful tradition we now call “Worship, Prayer, Food” (or, as Chris calls it, showing his priorities, “Eat, Pray, Love”). One Sunday a month, all the congregations of our region are invited to worship and eat together. Churches take turns hosting, and friendships continue to grow. Each time we meet to break bread, we are reminded of the miracle of healing and wholeness that was impossible to imagine only a few years ago.

We know that what has happened here in Inverell can happen anywhere. It happened in spite of us all, not because of us. “See, I am doing a new thing!”

To restore relationships and work as a united team is not an impossible goal. Sometimes all it takes to get started is one request for forgiveness—one crack in the façade, small enough for a grain of mustard seed to slide through, for something new to take hold and grow. There was no budget or agenda, no conference or seminar, just a simple welcoming of the Holy Spirit into hearts and homes and backyards. That, and a dying child who united us in prayer and shone a light on dark places in need of renewal.

Today, our town’s interchurch relationships aren’t perfect. But we serve a God who is forever writing new and better chapters, who can create paths where none were before, who can replenish and restore wilderness into fertile fields and unite disparate bodies into one.