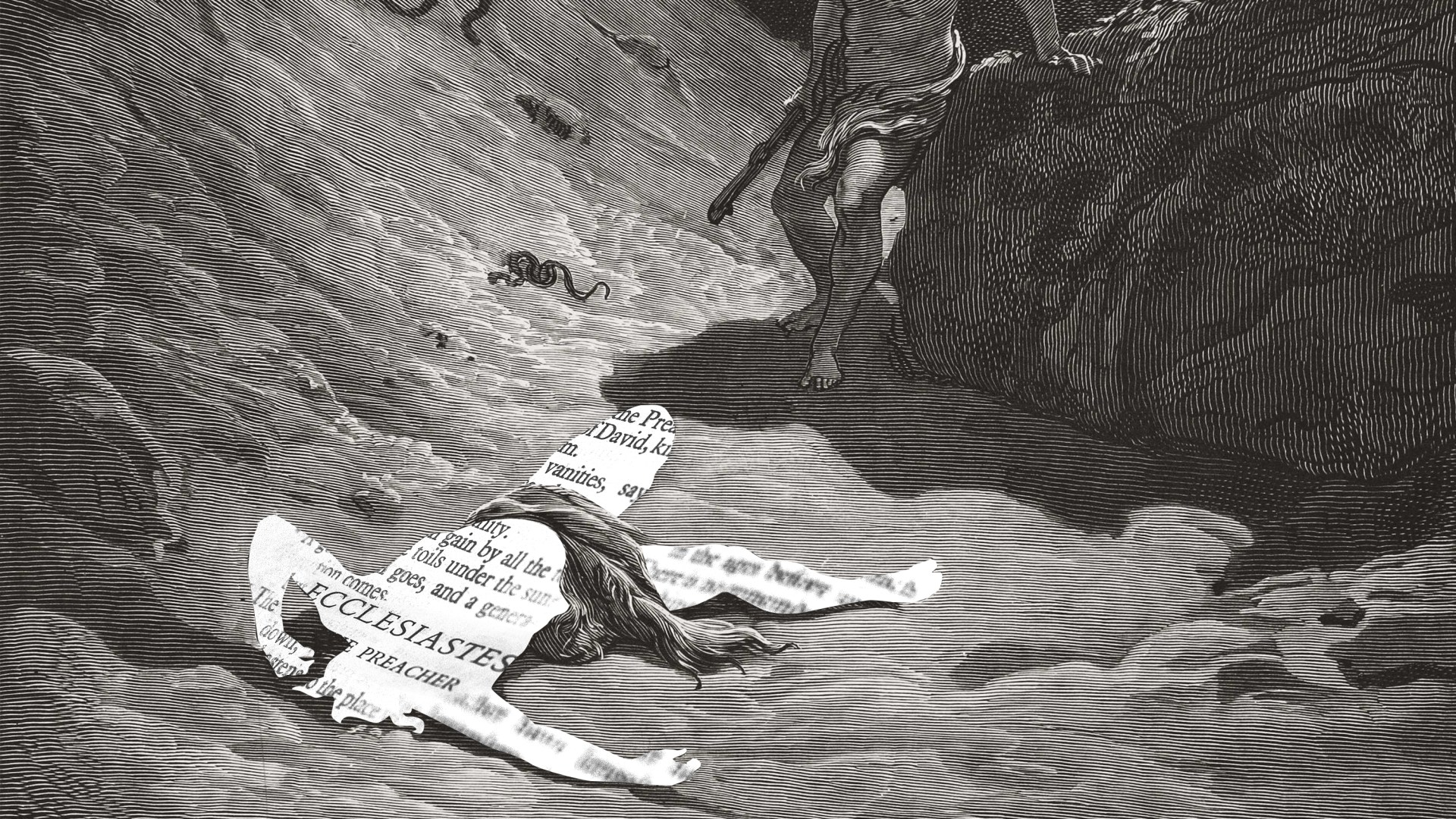

“Meaningless! Meaningless!” So says Qohelet, the author of Ecclesiastes, as he begins his reflections. “Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless.”

For many, these words resound with a skeptical and, some may say, nihilistic tone. But must they? Russell L. Meek, a gifted Old Testament scholar at Moody Theological Seminary, has endeavored to answer this question in his new book, Ecclesiastes and the Search for Meaning in an Upside-Down World.

Meek seamlessly weaves together scholarly insight, theological profundity, pastoral tact, and moving anecdotes drawn from his own experiences with pain, abuse, sin, and ultimately redemption in Christ. His work is quaint and accessible. I believe it will bless discouraged ministers and laypeople alike, and perhaps would make an excellent guide for a small group study or Sunday School class working through the book of Ecclesiastes.

Well-acquainted with ‘Abel-ness’

Meek begins by observing how Qohelet portrays our upside-down world—one tainted by human sinfulness and still reeling (to borrow from John Milton) from paradise lost. Meek suggests that Qohelet uses the creation narrative of Genesis “to remind us that sin is the ultimate cause for death and injustice in life.”

And yet, as Meek puts it, Qohelet teaches that when we enjoy “fleeting gifts from God,” we “return to the good that once was,” with “God’s gifts represent[ing] a portion of life before sin.” He further notes that, for Qohelet, even in a fallen world, God’s justice may be delayed (Ecc. 8:11), but it is never denied (3:17, 8:12, 12:14).

As for the time between the lost paradise of Eden and the arrival of God’s final justice, Ecclesiastes tends to sum it up with the word vanity. Meek devotes a helpful section to exploring Qohelet’s use of this notoriously difficult term. The Hebrew is hebel, which doubles as a word both for futility and the name of the slain brother in Genesis 4. Meek has coined (at least, to my knowledge) a neologism to capture more fully and faithfully the stark picture of the human predicament painted in Ecclesiastes: “Abel-ness.”

“Abel’s life illustrates Ecclesiastes in living color,” Meek writes. Ecclesiastes teaches us that Abel’s predicament is our predicament. Just as his life was marked by “transience, the broken relationship between actions and rewards, the injustice suffered, the inability to attain lasting value,” and “the failure of the retribution principle,” so too are our lives irrevocably stamped by various abuses and injustices.

Meek is well-acquainted with this “Abel-ness.” Part memoir and part exegesis, his book records his own struggles with this twisted, sin-laden, and upside-down world. Recounting his experience of coming to terms with being abandoned by his now deceased father, grieving the loss of his grandmother, and turning to a life of alcohol and substance abuse, he demonstrates that his words are not merely theoretical. They are marked by real suffering that calls to mind the senseless cruelty visited upon Abel.

It was difficult for me to read these words without being thrown back on my own experiences with abuse, injustice, and sin. After an abusive sexual encounter at the age of four, I wrestled (and will likely continue to wrestle) with feelings of guilt and sexual confusion. At five, social workers dragged my older brother and me from our home. At ten, my brother (who was 18) senselessly died in an accident. Then, on the day of his funeral, my grandparents were tragically killed in a car accident on their way home after the service.

Meanwhile, I clung to bitterness and resentment, and I despised the legalism that surrounded me in church. During my time at a Christian college, as I attempted to work through issues of sexual guilt and confusion, my trauma gave way to egregious patterns of sinfulness. This included jesting and time-wasting with a company of foolish so-called friends, along with the abuse of alcohol. I, too, have experienced the incredibly senseless, cruel, and debilitating “Abel-ness” of life.

Because human life is marked by this “Abel-ness,” perhaps we are all tempted to despair of life itself and, in the spirit of our age, conclude that this is all an exercise in futility. John Stott powerfully took note of this in his classic 2003 work, Why I Am a Christian. Stott argued that what he and others have called “the technocratic society” is marked by a “social disintegration” that “diminishes and even destroys transcendence and significance.” Must we despair, then, in a floundering human society in which it is easier to rage at our fellow image-bearers than to suffer lovingly with them?

The end of the matter

Qohelet does not offer an exhaustive to-do list, a comprehensive framework for handling suffering, or a convenient coping mechanism. All the same, Meek argues that he “guides us through the vagaries of life in this fallen world, offering the solution for how to navigate such a dark and twisted place.” And where, ultimately, does our inspired guide lead us? Back to the twin foundations of biblical righteousness: fearing God and keeping his commandments (Ecc. 12:13).

As Qohelet teaches, when we trust that God directs us our lives and gives us commands in his fatherly providence, we are free to enjoy God’s good gifts of food, drink, vocation, and friendship. When we live our lives acknowledging God’s reign—even over our “Abel-ness”—we experience what Meek calls an ever-so-brief “reaching back to Eden.”

But the story of Ecclesiastes remains incomplete on its own. It is one thing to reach back to Eden. It is another to look forward to a better one. Where Meek’s book shines brightest, in my opinion, is in its ringing affirmation that Jesus Christ is the ultimate key to understanding Ecclesiastes—and indeed all of Scripture.

In the book’s final section, Meek presents a Christ-centered interpretation of Ecclesiastes, which alone makes the book well worth the price.

“We know the harsh reality of living in the upside-down Abel-ness of this world,” he writes, “but we can also enjoy the temporal gifts God gives to us and more fully understand what it means to fear God—to trust him as our Father—because we know that God became man. By his life, this God-man, Jesus Christ, showed that this world is indeed turned upside down, and like Abel (Gen. 4:10), Jesus’ blood cries out. Unlike Abel, however, Jesus’ blood doesn’t cry out for justice. His blood cries out as justice, justice that reconciles sinners to God, that makes brothers out of enemies, that secures our place in God’s great family.”

This truly is the end of the matter!

David Bumgardner is a writer and minister located in New Orleans, Louisiana. He is a pastoral intern at Canal St. Church, a parish in the Anglican Mission International, and an ecumenical contributor to Baptist News Global.