Years ago, a friend told me about an awkward conversation with a female coworker. In between meetings, he had mentioned a Wall Street Journal article about declining college enrollment for men across America, a trend so advanced that men now trail women by record levels and colleges are ramping up their efforts to recruit men. Expecting a sympathetic response, he was caught off guard when she declared, in a nonplussed tone, “And now whose fault is that?”

At this point, he remembered that his coworker was a strong advocate for women’s rights. He guessed her harsh response was pinned to a belief that sympathy for men would detract from women’s longstanding struggle for gender equity. Yet he didn’t want to picture these causes as locked in a zero-sum contest. As he put the question to me one afternoon, “Can’t we care both about women’s rights and vulnerable men and boys at the same time?”

It’s a good question.

Richard Reeves’s groundbreaking book Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do about It makes a convincing case that men across the modern world are indeed struggling and need our attention.

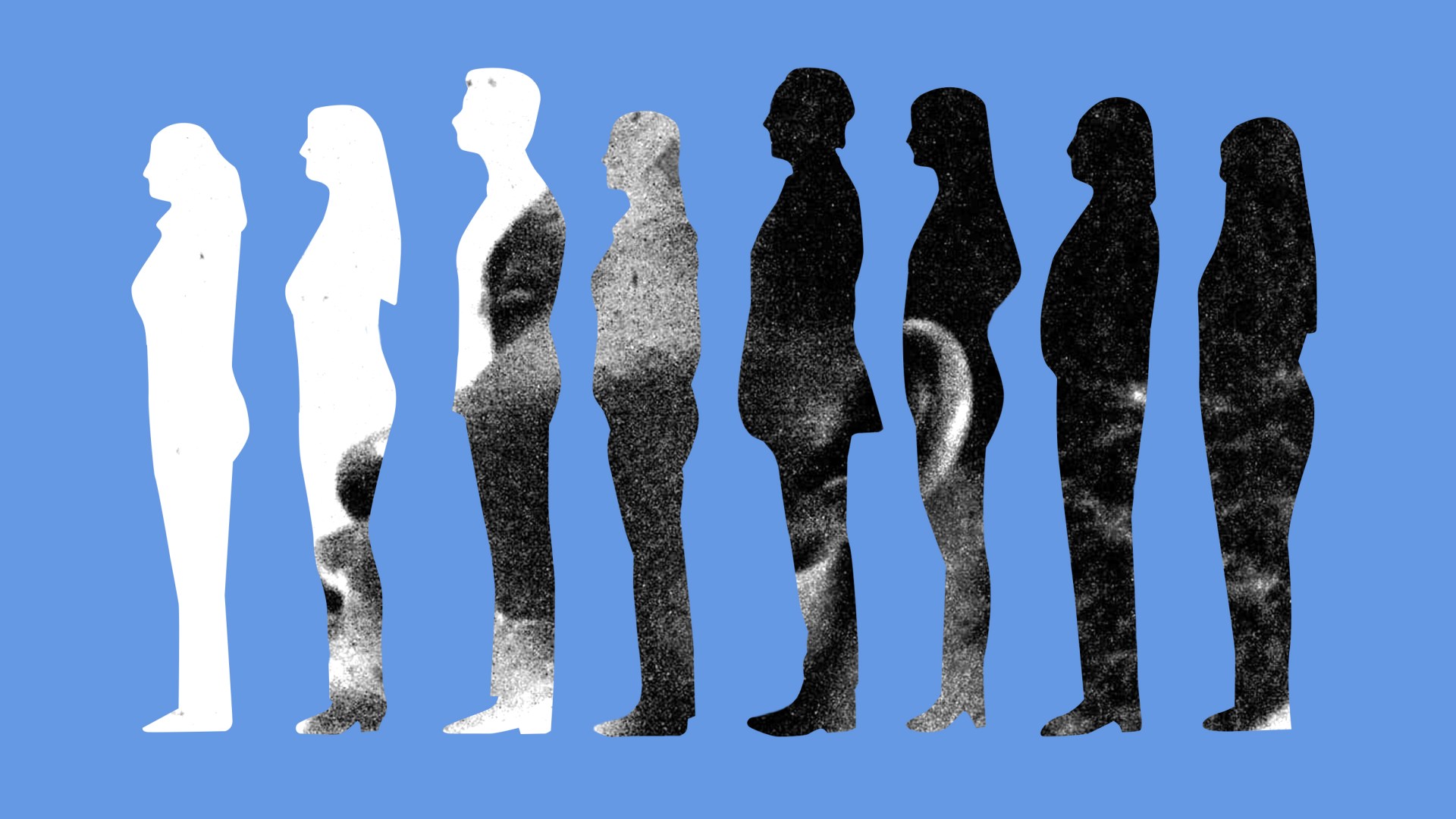

Losing ground

Reeves, a Brookings Institution scholar, marshals an array of eye-opening statistics to make his point. For instance, did you know that girls regularly outperform boys in education? Girls are 14 percentage points more likely than boys to be “school ready” at age five, and by high school, girls now account for two-thirds of students ranked in the top 10 percent, according to GPA. The gender gap widens even further in higher education: In the US, 57 percent of bachelor’s degrees are awarded to women, and women receive the majority of law degrees. In contrast, men are significantly more likely to “stop out” (pause their studies) or drop out of college.

Men are also losing ground in the labor market. Labor force participation among prime-age men (25–54) has dropped by 7 percent in the past half century, due at least in part to automation and a shift away from well-paying manual-labor jobs to a service economy. The median real hourly wage for working-class men peaked in the 1970s and has been dropping since. And while it is true that men tend to make more than women, Reeves shows that the gender pay gap is largely a parenting gap, in that it has all but disappeared for childless young adults. We primarily have women, not men, to thank for rising middle-class incomes since the 1970s.

And dads are increasingly in short supply. Traditionally, the male role was culturally defined as a provider for the family. But with greater economic independence for women (a good thing), men are increasingly unable to fill the traditional breadwinner role. “The economic reliance of women on men held women down, but it also propped men up,” Reeves writes. “Now the props have gone, and many men are falling.” If men aren’t necessary as providers anymore, many men question whether they’re really necessary to families at all.

What’s puzzling scholars is that interventions to help men seem to not be helping. Take, for example, Kalamazoo, Michigan. Thanks to a group of benefactors, students in its K–12 education system can get their tuition covered for almost any college in the state. Women in the program experience large gains, including a 45-percent increase in their college completion rates, but men, as Reeves observes, “seem to experience zero benefit.”

Researchers have found similar results elsewhere. A student-mentoring program in Fort Worth; a school-choice program in Charlotte, North Carolina; a program to help low-income wage earners in New York—each shows significant gains for women and girls but not for boys and men. When asked why this is, researchers simply say, “We don’t really know.”

Something is wrong with men. And it’s a phenomenon Christians—both men and women—need to seriously consider.

Male malaise

Of Boys and Men has garnered widespread praise, and for good reason.

Reeves isn’t content to simply point out a dispiriting social problem and be on his merry way. He offers solutions. He argues eloquently that we should adopt policies that start boys a year later in the classroom to give their brains time to develop. He makes the case that we need to get men into “HEAL” occupations, meaning jobs in health, education, administration, and literacy—both because these jobs track with forecasts about the future of the workforce and because they help remove the stigma against men in traditionally “female” jobs, like nursing or elementary education.

Beyond this, Reeves argues, we need to make a major investment into fatherhood. “Engaged fatherhood,” he writes, “has been linked to a whole range of outcomes, from mental health, high school graduation, social skills, and literacy to lower risks of teen pregnancy, delinquency, and drug use.” It’s time to think about paid leave for dads, equal child-custody rights for dads after a divorce, and father-friendly, flexible job structures.

Reeves has written a tremendously thought-provoking, well-researched, and convincing book on the plight of the modern man. As a policy wonk, he proposes policy solutions. And yet, as a Christian, I couldn’t help thinking past the question of what to do, essential though it is, and wondering more about the question of why. What kind of male malaise is spreading in our culture?

In a piece for the journal National Affairs, Reeves offers a succinct answer: “The problem,” he writes, “is not that men have fewer opportunities; it’s that they’re not seizing them. The challenge seems to be a general decline in agency, ambition, and motivation.” Though this problem appears particularly bad for working-class men, professional men too are experiencing a broad, global slump in desire.

Since Reeves himself argues that policy interventions are rarely helping men, I couldn’t help but wonder: Have shifting economic and cultural norms around male roles have caused not just a social crisis but a spiritual one?

Humility and compassion

What does it mean to be a man? It’s a hard question for evangelicals to answer. Many Christian men know what they shouldn’t be. They shouldn’t conflate Jesus and John Wayne, say, or join the ranks of Christian nationalists. Despite their biological wiring to be more aggressive, risk-taking, and sexually driven than women (there really is science behind this), they know they shouldn’t be domineering or unfaithful. In short, they shouldn’t live down to the stereotypes of what we often call “toxic masculinity.”

It’s easy to mock chest-beating men’s ministries or criticize the “good old boys club” in a local chamber of commerce. It’s much harder, though, to come up with a pro-social definition of masculinity. Yet many men who’ve lost their sense of direction and purpose long for exactly this: a vision of manhood that both women and men can celebrate.

Of course, there are wonderful examples. Peter Ostapko’s beautiful Kinsmen Journal, a magazine heralding faith, fatherhood, and work, comes to mind. As does Arthur Brooks’s call to faith, work, family, and friendship. I think even an appreciation of the art of manliness can help. Yet these calls to healthy masculinity are too rare.

Christians can get to work here. We can normalize conversations among men about both work and fatherhood. We can—and should—invest more time in friendships. We can support lower-income neighbors and coworkers, we can embrace sexuality as a gift of God within marriage, and we can redefine “men’s work” to better include a wider array of occupations.

But can we graciously have a theological conversation about God’s design for both men and women? Can you imagine if women’s ministries discussed Of Boys and Men and men’s ministries discussed Beth Allison Barr’s The Making of Biblical Womanhood? Humility, after all, is a core virtue of the Son of Man.

I’m not sure this will happen any time soon. But after reading Reeves’s balanced, thoughtful book, I can confidently say that if you’re a woman and you know a man, he’s probably having a hard time. Show him compassion.

And if you are a man, well, let’s at least find a way to struggle together.

Jeff Haanenis a writer and entrepreneur. He’s the founder of Denver Institute for Faith and Work and the author of An Uncommon Guide to Retirement: Finding God’s Purpose for the Next Season of Lifeas well as the forthcoming books Working from the Inside Out and God of the Second Shift.