In the early 20th century, the gates of Tibet were still tightly shut to Christian missionaries.

The people who lived across the Tibetan Plateau were devout believers in Tibetan Buddhism. One out of every four adult males was a lama (monk). At that time in history, infectious diseases such as syphilis, leprosy, smallpox, plague, and diphtheria were rampant. Due to the lack of medical care, the only method of prevention was to isolate the sick, even to the point of casting them out of the community for life.

A good number of missionaries from the China Inland Mission (CIM) hoped to share the gospel with Tibetans. But because they could not enter Tibet, they could reach Tibetans only through neighboring provinces. As early as 1918, missionaries Harry French Ridley and Frank D. Learner began spreading the gospel in Qinghai Province. By the end of the 1940s, there were an estimated 200 believers in eastern Qinghai, but few to no Tibetans among them.

That would eventually change. Also in the 1940s, a CIM missionary served in medical missions among the Tibetans in Gansu and Qinghai Provinces: the English medical doctor Rupert Clarke.

During Clarke’s youth, he often stayed at his grandmother’s Victorian manor, where the family would gather several times a day for prayer and where attending church on Sunday was a given. Although biblical knowledge filled young Clarke’s mind and he lived in a rule-abiding manner, he lacked the assurance of salvation in his heart.

This continued until he attended university and joined a Christian fellowship. There he met fellow students Robert A. Pearce and James Cecil Pedley. Pearce and Pedley felt that while Clarke had the appearance of being a Christian, he had not tasted the joy of salvation, so they often prayed for him. When Clarke read one of the books they lent him, he finally realized that the assurance of salvation rests on God’s promises, not on human efforts. What he needed was trust in Jesus. He knelt by the bedside and welcomed Jesus into his heart with Revelation 3:20. He never looked back.

Clarke went on to study in medical school. During the summer of his third year, he contracted mumps that confined him to bed in his grandmother’s home. During that time he read the book A Thousand Miles of Miracle in China, which details the dangerous trek of the Glover family, missionaries who were taken from Shanxi to Shanghai during the Boxer Rebellion. Clarke was deeply moved and began to care about the needs of people in China.

Lanzhou Hospital

Pearce and Pedley joined the CIM in 1931 and 1935 respectively and served in the Lanzhou Hospital of Gansu as well as the affiliated leper hospital. Many of the Tibetans in the leper hospital came to believe in Jesus. The two missionaries continually wrote to encourage Clarke, and his burden for the Tibetans deepened daily. Finally, Clarke joined CIM’s Tibetan medical missions team and went to serve in Lanzhou, Gansu Province.

By 1941, Clarke’s work in the Lanzhou Hospital was making progress. In the same year, the CIM invited him to join the work of the medical missionary team in Zhongwei, which was five days’ travel into the neighboring province of Ningxia. Clarke arrived in Zhongwei but had come down with severe hepatitis and was yellow all over. The CIM immediately sent nurse Jeannette Barbour to take care of Clarke.

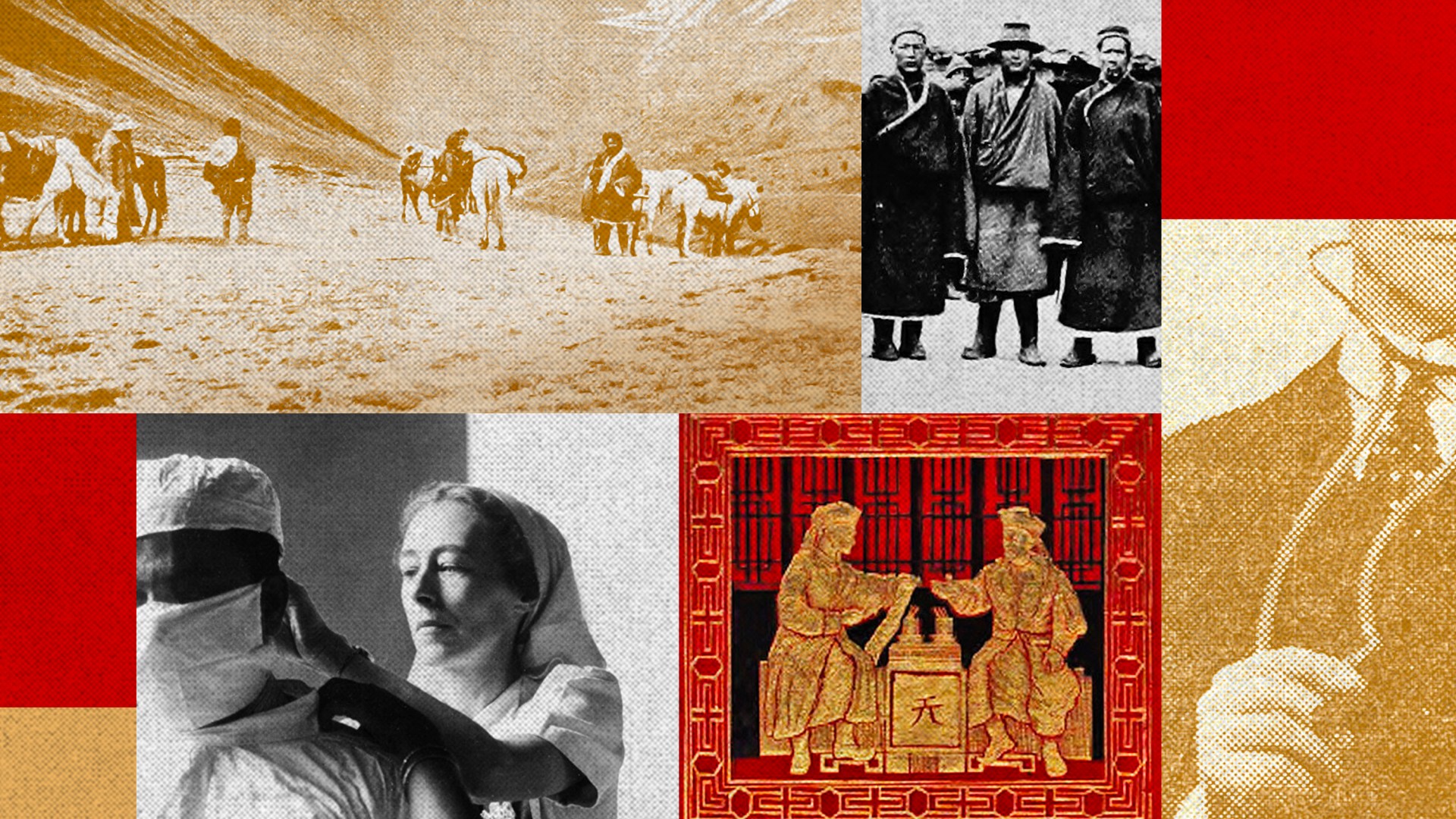

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: WikiMedia CommonsBarbour was born in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and trained as a nurse in Edinburgh, Scotland. She had just recently joined CIM at the time. Under Barbour’s careful care, Clarke quickly began improving but had to remain in Zhongwei as he recovered. A month later he was healthy enough to bike back to Lanzhou. By then, he had already quietly become engaged to Barbour, though they had to wait to marry until she had served a full two years and passed her language exams according to CIM rules. On January 14, 1943, the two held their wedding in Lanzhou, by the shores of the iced-over Yellow River.

In 1944, after the end of World War II, Clarke was in charge of CIM’s hospital in Lanzhou city. At the end of 1946, the couple returned to England and South Africa on home assignment, and CIM sent Alfred James Broomhall to take over the medical work in Lanzhou.

Many Tibetans sought medical care at the Lanzhou Hospital and the affiliated leper hospital, and large numbers of them had to travel for weeks and even months. Han Chinese were generally unwilling to share a room with Tibetans, so the hospital set up wards specifically for Tibetans. The records of 1947 show that at least 80 Tibetans stayed at the hospital. Patients who required long-term care were often transferred to standard wards, and some of them had to stay for months. The Tibetans who were accepted and received medical care were thankful, but no missionary was available to share the gospel with them in the Tibetan language.

Hualong Medical Station

For many years, the CIM had planned to open a small hospital in Qinghai Province so the Tibetans spread across Qinghai could hear the gospel. In 1948, Clarke sent out a plea to his supporters back in the UK: Because of the lack of medical staff, the plan for a Qinghai hospital was on hold, and he was praying and planning fervently for God to send workers from the East and the West to serve the Tibetans.

In early 1948, Clarke returned to China after home assignment, but CIM was still unable to open the Qinghai hospital due to a lack of workers and resources. Right at that time, the board of the Holy Light School received aid from the “China Aid Team” and gifted the Lanzhou Hospital a large number of medical supplies left by the American military, allocating three tons of supplies to Hualong in Qinghai Province. CIM immediately reassigned workers and sent a local doctor as well as four nurses to the medical work in Qinghai Province. Clarke’s dream of many years to set up a medical station at Hualong was finally realized.

Hualong lies south of Xining city, near the boundaries of Qinghai and Gansu Provinces. It sits 10,000 feet above sea level and has thin air. The ground is unfrozen only four months of the year, and only in August is there no snow. For Clarke, transportation was challenging, but he was optimistic, adaptable, and unfazed by obstacles. Nothing was too difficult for him. On one occasion, his car’s fuel pump broke down. Clarke pulled his stethoscope out of his medical bag, held the gas can on top of the car, and guided the gas through the tube of the stethoscope and into the engine. The car was fixed, and he could continue on his way.

On July 5, 1948, Hualong Clinic officially opened. Dignified Buddhist lamas and monks and influential Muslim imams lived among the people in Hualong. Clarke and his fellow workers began handing out gospel tracts in Chinese and Arabic in the city.

In 1949, Rupert and Jeannette, who was pregnant with their first baby, moved and settled in Hualong. The couple was of the same mind—unafraid of hardships, all for the sake of serving the Lord of their lives and the Tibetans whom they loved.

They grew the clinic into a facility that they named Holy Light Hospital, with 20 beds. That same year, they saw as many as 3,590 patients and performed 160 surgeries. Jeannette held their newborn son, Humphrey, in one hand and carried out her nursing duties with the other.

Word of the hospital and Clarke spread far and wide. People said, “This foreign doctor is very good to Tibetans, treating them the way he treats Han Chinese.” Sometimes traveling for weeks, Tibetans and lamas came on horses, on yaks, or on foot in large groups to seek medical treatment. When they arrived at the hospital, they would hear the gospel for the first time, undergo surgery, recover, and joyfully return home with a New Testament or gospel pamphlets.

The beds were often full. Sometimes patients had to leave before they were fully recovered to make space for more seriously ill people flooding in. There were simply not enough beds. Up to 20 or 30 patients might be squeezed on the heated brick bed reserved for the relatives. But Clarke thought that serving Tibetans was “a great deal” because they had a strong will to live and were grateful. Clarke particularly hoped that Han Chinese Christians would join in sharing the gospel as well. In the 1950 issue of CIM’s China’s Millions journal, Clarke wrote:

What excited Clarke even more was that a clan in the mountains of Tibet had sent someone to visit and invited him to start a hospital where they lived. They even promised to supply a house and everything he might need. Naturally Clarke was ready to go right away, but it was not to be.

Evacuating from China

In December 1950, under dire circumstances, CIM’s leadership decided to fully withdraw from China. By January 1952, only 33 of CIM’s 620 missionaries remained stranded in China, including the Clarke family.

In June 1951, Chinese officials charged Clarke in Hualong court with many crimes, the most severe of which was being a spy for Western countries. Of course, Clarke firmly denied this. His wife and children were permitted to leave, but the officials imprisoned Clarke and confiscated the Bible in his bag. Yet he quietly sang, “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” Over 40 prisoners—many of them Muslim—filled the cell, and there was nowhere to sit but the ground.

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: WikiMedia CommonsClarke was later released but held under house arrest in Hualong Hospital, cut off from the outside world. To keep his body and mind strong, he insisted on walking three miles daily in the hospital courtyard, along with a weekly ten-mile walk, so that if he should be released one day, he would have the strength to walk to Xining. Clarke was later transferred to Xining and held at CIM’s missionary center.

In the afternoon of July 20, 1953, Clarke and Robert Arthur Mathews (another CIM missionary in northern China serving Mongolian people) arrived in Hong Kong by train and were the last two CIM missionaries to leave China. Arnold J. Lea, overseas director of CIM, wrote the following conclusion in the 1951 issue of China’s Millions:

The Communist government shut down the Hualong Hospital in 1950, marking the end of the missionary era to evangelize the Tibetans in Gansu and Qinghai. However, in the same year, two CIM couples (George and Dorothy Bell of Canada and Norman and Amy McIntosh of New Zealand) baptized two Tibetan women “who possessed a true faith in Jesus Christ.” Then Tibetans in India reported the joyful news that a group of Chinese Han Christians shared the gospel with Tibetans in Labrang (a Tibetan town in southern Gansu), “resulting in 20 professions of faith.”

In today’s China, reaching the Tibetan people with the gospel is still extremely difficult and sensitive. But more Han Christians are involved in evangelizing diaspora Tibetans in Chinese provinces outside Tibet. It is our prayer that the Spirit that inspired Rupert Clarke doubly inspires Chinese Han Christians today and that they will take the baton to share Christ’s love to Tibetans.

Translation by Christine Emmert