As a freshman at Biola University, Grace Brannon (née Kim), 28, encountered many Korean and Korean American women with the same first name. When several of them became part of the same friend group, they started to call themselves Grace 1, Grace 2, and Grace 3.

“This was like an inside joke among our friend group. It was funny,” Brannon said. “They knew a lot of other Graces too.”

The ubiquity of the name Grace among predominantly East Asian and East Asian American women has been both anecdotally remarked upon and at times given larger cultural attention. When I shared social media posts asking to connect with Asian women named Grace for this story, one person tweeted, “I know fifty.” Another said that CT would need “3 issues and a podcast” to adequately represent the plethora of Graces in Asian American communities.

In 2005, filmmaker Grace Lee even made a documentary as a way to uncover the stereotypes and social expectations people had for women bearing, in this case, both her first and last name.

“In the US, most of the Graces I know are Chinese or Korean,” said Grace Chan McKibben, 55, the executive director of the Coalition for a Better Chinese American Community in Chicago. She moved to America from Hong Kong in high school.

“My grandma, aunt, and sister-in-law are all named Grace,” she added.

What’s so amazing about the name Grace? Why do so many Asian Christian women in North America have this name? Perhaps the name represents a believer’s cry while living in a foreign land, and a proclamation of thanksgiving for receiving undeserved kindness from God.

Divine intervention

Grace comes from the Latin word gratia and was not particularly common in the English-speaking world until the 17th century, when the Puritans began naming their children “virtue names” like Felicity and Prudence. More recently, Grace peaked in the US in 2004 when it ranked 13th on the Social Security Administration’s list of female baby names. Last year, it was No. 35. In Canada, Grace ranked 31st in a list of most popular female baby names in 2020.

Little seems to have changed since the Grace Lee documentary. The name is still going strong today in Korean and Chinese immigrant circles. As one Harvard social sciences researcher discovered, Grace is five times more popular than most names among Chinese Americans.

The name was also common among the wartime generation of Japanese Americans. During World War II, 636 women of Japanese descent named Grace were incarcerated by the US. Many of them have since spoken up about their horrific experiences in these prison camps as a way of reclaiming their stories. Grace Oshita, a San Francisco native, has traveled around Salt Lake City for 40 years to talk about her incarceration in California and Utah, and Grace Amemiya, who was detained at 21 years old and spent a year in an Arizona camp, chose to “radiate grace” and forgiveness toward the American government.

In other words, move over, Connie: Grace is the real Asian baby name trend. But whereas the proliferation of Connie traces back to one very famous journalist, the nine Graces who spoke with CT offered diverse explanations for how their parents found their name.

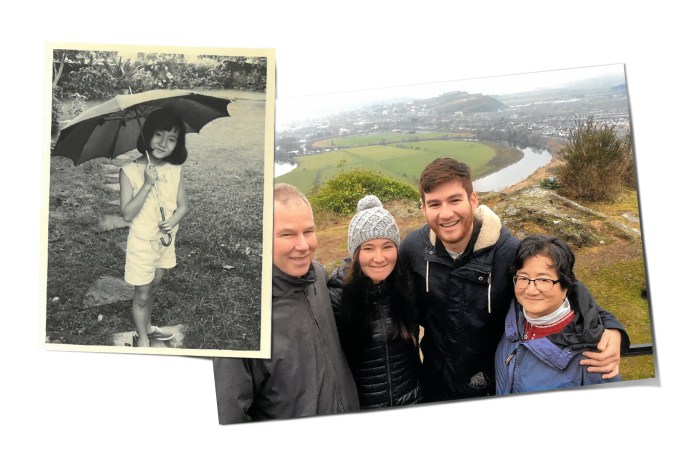

Courtesy of Grace Boneschansker and Grace Nobleza

Courtesy of Grace Boneschansker and Grace NoblezaGrace Nobleza, in her mid-50s, and Grace Boneschansker (née Nagasuye), 64, both Canadian residents, cited Grace Kelly, the former princess of Monaco, as their parents’ inspiration. When they were born, the American actress had recently married Prince Rainier and was a well-loved icon around the world.

Others had Christian parents who found the name an important representation of God’s undeserved favor, like Grace Liaw Bliss, 33, who is Malaysian Chinese and moved to the US to attend Wheaton College. (Her sister’s name: Mercy.)

Several women also have Chinese and Korean names that are synonymous with their English names. Chan McKibben’s Chinese name, Ben En, contains the character 恩 (en) for “grace.” Grace Chen, 40, is a New York-based occupational therapist whose Chinese name, Zhen En, means “precious grace” and was given by her paternal grandfather.

Brannon’s Korean name, Si-eun, has the Korean character 은 (eun) for “grace” as well. Grace Park, 40, has a popular Korean name that translates as “grace” or “favor” in English: Eun-hye. (Park’s last name is a pseudonym, as she has served as a missionary in a sensitive context for 12 years.)

Courtesy of Grace Ju Miller

Courtesy of Grace Ju MillerThe name also reflects miraculous instances of God’s hand at work, as it was for Grace Ju Miller, Taylor University’s dean of natural and applied sciences. When Miller’s mother was pregnant with her in the Philippines, she discovered a cyst in her womb and a doctor advised her to abort the child. A second doctor, however, said the baby was fine and put her on bed rest. The bleeding stopped, and Miller, now 64, was born a perfectly healthy baby.

Grace Cho, 26, was born in South Korea and immigrated to the US at 18 months so her father could pursue a theology degree. While in South Korea, Cho’s mother did not know she was pregnant and went to the hospital to receive antibiotics for treating an illness. Doctors told her that it was unlikely her baby would survive after taking the medication.

Cho’s mother decided to consult doctors at a Christian hospital instead. There, hospital staff said they would pray for both mother and child. Cho was born nine months later without any ill effects, and her birth was a sign of God’s grace in her parents’ eyes.

“To me, the name Grace represents how I’m meant to be here, [even when it’s been] difficult to fit in,” Cho said. “I love my name.”

An evangelical impulse

Nevertheless, for North American–born Graces, the popularity of the name cannot be attributed simply to its celebrity factor, its commonality with words in other languages, or as a celebration of God’s faithfulness. Evangelicalism has also influenced the name’s prevalence in this part of the world.

Courtesy of Grace Cho and Grace Brannon

Courtesy of Grace Cho and Grace BrannonGrace reflects “one of the core values of the evangelical tradition,” Park, the missionary, mused. “There’s not many words … that could be translated into a child’s name. Maybe this has become one of those acceptable words.”

“Even when picking anglicized names for their kids, immigrant Asians have tended to gravitate toward a short list of options—generally, biblical names, reflecting the relatively high percentage of evangelicals among later waves of Korean and Chinese immigrants,” wrote then–SF Gate reporter Jeff Yang in 2006.

Christian names like Grace may well be an easy way for immigrants of Asian descent to assimilate into a foreign country like America or Canada.

In a society where “Christianity has cultural, social, political power, it helps you to be Protestant, to have that affiliation, and have Christian names,” said Daniel D. Lee, Fuller Seminary’s academic dean for the Center for Asian American Theology and Ministry.

“Biblical names are quite American.”

Historically, converting to Christianity and attending church improved immigrants’ status and helped them appear more “American” and less foreign.

The majority of Chinese and Korean immigrants arrived in North America from 1965 onwards, after legislation in the US and Canada repealed decades of discriminatory measures intended to keep them out. Those who had managed to migrate earlier contended with legislation that often kept them second-class citizens.

Becoming a believer, or adopting a Christian name at the very least, may have been a helpful response in these Christianized contexts.

“Christianity and prosperity were conflated together, which is problematic, right? But that’s how they perceived it. It was white, Christian, prosperous, and powerful. That’s how a lot of immigrants perceived [the] US to be,” Lee said.

Great expectations

For all these efforts at assimilation, the name’s religious connotations may well add another layer of complexity to formulating one’s identity in North America.

“In the US context, the racialization of Asian American women has meant that they are portrayed as exotic, sexualized, subservient, quiet, nice. Religious [names] add the expectation that this person is going to be kind and won’t make a fuss,” said Sabrina Chan, InterVarsity Fellowship’s national director of Asian American Ministries.

Modesty and compliance were some of the common attributes for Asian American women named Grace Lee in the 2005 documentary. “The attributes [in the film] feel really relatable. These are the same kind of values that are encouraged in Asian girls,” said Park, who was born in South Korea and moved to Southern California when she was 10 years old. “I live up to all those kinds of expectations,” she quipped.

Most of the Graces CT interviewed said that they have received overwhelmingly positive responses about their names from people inside and outside the church, such as “You live up to your name” and “I want to name my kid that.”

Some regard their name as a powerful way to evangelize. “I was a rebellious teenager. God turned [my life] upside down,” said Boneschansker, the Japanese Canadian. “I feel special. It’s very biblical. I get to use [my name] as a witness to non-Christians.”

Others, however, have struggled with the overtly Christian expectations that are typically associated with the name.

Courtesy of Grace Liaw Bliss

Courtesy of Grace Liaw BlissBliss’s parents would often say to the siblings, “You’re Grace and Mercy. Don’t fight. Share with each other.” “They used our names as motivation: ‘You should be like this,’” said Bliss, a homemaker who still lives in Wheaton.

“Right now, people in general will say, ‘Your name is fitting.’ It’s a compliment, but also pressure. [I feel like] I better measure up to this expectation,” Bliss added.

Nobleza, who works as a psychotherapist in Vancouver, Canada, often felt pressured to show grace to everyone she met. This perspective arose from being subsumed in a largely Catholic environment in the Philippines which colored her worldview into one that focused predominantly on doing good works. Displaying nasty or rude behavior to someone was not a good reflection for someone with the name Grace, she said.

“The realization that I need to receive grace for myself only happened in my 40s,” Nobleza said.

Brannon spent her college years as “Gracey” before reverting to “Grace” two years after graduation, as she felt it sounded more professional in the workplace. (Brannon was previously a marketer at CT.) For her, a living example of God’s grace to her family is her one-and-a-half-year-old daughter, who also bears an explicitly Christian name: Faith.

“When I was pregnant, I thought a lot about my parents and the heritage of faith they left. By earthly standards, they don’t have a lot. They don’t have money, investments, or property. Their biggest gift and inheritance they passed on to us is their faith,” Brannon said.

“My desire as a parent is to pass on this legacy of faith from my grandparents down to my own daughter. As long as she comes to trust the Lord, I will be happy.”