Think of something big and important happening in the world—some cultural trend, political movement, or social craze. Chances are that someone, somewhere, has proposed giving it a distinctly “Christian” or “biblical” framing. Some of these efforts, aimed at glorifying God in all things, supply helpful correctives to secular errors. Others, smacking more of anxious attempts at hopping aboard a moving train, add little beyond a thin spiritual gloss.

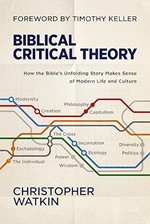

Thankfully, CT’s book of the year, Christopher Watkin’s Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture, belongs to the first category. Some might wince at the mention of critical theory, with its perceived reputation for nonsense jargon or radical politics. Critical theory comes in many flavors, of course, some guiltier than others of cramming messy human particulars into ideological straitjackets. But the late Tim Keller, in his foreword, suggests another view, observing that a good theory “make[s] visible the deep structures of a culture in order to expose and change them.”

As Watkin contends, Scripture does this better than anything else. Other critical theories—derived from deep analyses of race, gender, psychology, language, and law—might apply useful lenses to reality. But all are clouded or cracked to some degree, requiring a higher wisdom and a truer story to polish off the smudges and patch together the broken shards. God’s Word, in this sense, does more than explain God to the world. In unsurpassed fashion, it explains the world to itself.

Like Biblical Critical Theory, all of our award winners contain insight and beauty on their own. And like all good books, they are made complete in the greatest Book of all. —Matt Reynolds, senior books editor

Apologetics/Evangelism

The mountains of Appalachia have many faces. One face, shown mostly to vacationers, is picturesque mountain people sewing quilts and playing dulcimers by wood-burning stoves. A different face reveals how Appalachia’s hills and hollows have been left scarred and denuded by overdevelopment. And yet another face exposes how rural families have been hurt for generations by alcoholism, violence, and depression.A true portrait of Appalachia, perhaps, blends together all these differing images, telling a story with more sadness than triumph, with more sorrow than joy.Three-fourths of the poor in the United States are white people living in rural areas. The greatest concentration of those poor people is in Appalachia, which is home to 22 million people. Illiteracy stands at 35 percent in the 397 counties of the region, and 15 percent of the homes still have no telephones.“What we have here,” says Karen Main, deputy director of the University of Kentucky’s Center for Rural Health, “is extensive grain-alcohol abuse, family violence, homicide, accidents, substance abuse, and depression.”The economy of Appalachia has collapsed. Coalmining jobs, light manufacturing, and federal assistance have largely dried up. Today, most of Appalachia’s people work at the marginal jobs that remain. The average annual income for a family of four in West Virginia is , 000.“I’ve been in ministry for 30 years and have never seen more poor people,” says Mary Lee Daugherty, executive director of the Appalachian Ministries Educational Resource Center, based in Berea, Kentucky.Daugherty knows hard times from the inside. Daugherty and her brother, Jim—both brown-eyed and red-headed—grew up in the home of a West Virginia miner and factory worker. Their mother died in their early teen years. Their father drowned his grief in alcohol.Drawn close through adversity, the children found hope in their hometown church. Daugherty came to Christ through the influence of the Sunday school. Jimbo went forward in a tent meeting at age 15. Within two years, his life completely turned around; soon he was directing a local Youth for Christ group.The twosome ministered together in small-scale revival services. He preached; she played the piano or sang, and the determined duo earned their way through college. Afterwards, she went on to seminary, and Jim moved into national ministry with Youth for Christ. Daugherty set her sights on missionary work, thinking there she might find more freedom to use her gifts.Arriving in Brazil, she was struck by the pervasive poverty and quickly became involved with the women of struggling families. Their plight closely paralleled her Appalachian experience. Chuck, a son of American missionaries to Brazil, was one of Daugherty’s fellow teachers. They were married and gave birth to a daughter and son, and eventually returned to the States.Back in Charleston, West Virginia, Daugherty cared for children during the daytime, yet found spare time to teach religion courses at a local college. She quickly discovered that many pastors coming into the region were unprepared for the culture shock that comes from ministry to the rural poor. Working with local church leaders, Daugherty set up an orientation program for new pastors. But she had to abandon the classes when her college dropped its commitment to religious studies. Then, 11 years ago, the Commission on Religion in Appalachia (CORA) asked Daugherty to start a training program for individuals planning to minister in Appalachia. In 1985, the Appalachian Ministries Educational Resource Center (AMERC) in Berea was born. AMERC is a trio of hands-on experiences designed to give pastors the skills they will need to work among the chronically poor:• The January Travel Seminar, an intensive session taking students to family farms, strip-mine sites, and cooperative parish ministries.• On-site rural internships, in which students work directly in parishes.• Summer Term, a six-week program taught at Berea College, where students spend much of their time living in a community.A major reason that AMERC succeeds is Daugherty herself. Out in public, she is persuasively direct, talking about poverty without playing up sentimentality. Daugherty’s unassuming intensity is relieved by a distinctive laugh. She will, says a staffer, “rare back and let out a belly laugh” at herself and the bizarre situations that shoe-string operations frequently find themselves in. That humor helps her staff to “run but not faint.”AMERC’s mission is to strengthen church leadership in Appalachia by recruiting and training clergy and lay professionals for long-term service. Students may learn how to strengthen the churches by working with local people, how to teach in a low-literacy environment, cultivate a garden, or do canning in the church kitchen.The old Pearson Farm, donated anonymously last October, has given AMERC a campus. The farmhouse has been remodeled and its garage has been converted into a library. Typical of Daugherty’s unstinting hospitality, this winter she housed volunteer workers in her own apartment and prepared meals.In February, friends gathered to dedicate the library. The library fund is named in memory of Daugherty’s brother, who died of cancer last year.Daugherty is equally gracious and comfortable with feminists and fundamentalists. As a result, AMERC is thoroughly ecumenical—including Protestants, Roman Catholics, and the Orthodox. J. Steven Rhodes, AMERC’s associate director for academic affairs, says he treasures the memory of a monk, an IBM executive, and a snake handler washing each other’s feet at the service that ended a recent summer term.Daugherty believes the high level of cooperation has been achieved in Appalachia “because we’ve been poor longer, long enough to no longer look to big government or big business, long enough to be asking, instead, ‘How are we going to help ourselves?’ ”Governed by CORA, Berea College, and 45 sponsoring theological institutions, AMERC is now the largest cooperative alignment of seminaries in America. AMERC has trained 439 seminary grads from 37 denominations.Daugherty points out that since there are not enough big-steeple churches to go around, more than half of all seminary graduates will end up in small-town and rural pastorates. Her goal is to train them to cope so that she can successfully appeal to each to give 15 years in service among the rural poor.By then, she figures, the new influx of resources into the mountains will be under way. Meanwhile, don’t underestimate this spunky angel for Appalachia.By Harry Genet.

The mountains of Appalachia have many faces. One face, shown mostly to vacationers, is picturesque mountain people sewing quilts and playing dulcimers by wood-burning stoves. A different face reveals how Appalachia’s hills and hollows have been left scarred and denuded by overdevelopment. And yet another face exposes how rural families have been hurt for generations by alcoholism, violence, and depression.A true portrait of Appalachia, perhaps, blends together all these differing images, telling a story with more sadness than triumph, with more sorrow than joy.Three-fourths of the poor in the United States are white people living in rural areas. The greatest concentration of those poor people is in Appalachia, which is home to 22 million people. Illiteracy stands at 35 percent in the 397 counties of the region, and 15 percent of the homes still have no telephones.“What we have here,” says Karen Main, deputy director of the University of Kentucky’s Center for Rural Health, “is extensive grain-alcohol abuse, family violence, homicide, accidents, substance abuse, and depression.”The economy of Appalachia has collapsed. Coalmining jobs, light manufacturing, and federal assistance have largely dried up. Today, most of Appalachia’s people work at the marginal jobs that remain. The average annual income for a family of four in West Virginia is , 000.“I’ve been in ministry for 30 years and have never seen more poor people,” says Mary Lee Daugherty, executive director of the Appalachian Ministries Educational Resource Center, based in Berea, Kentucky.Daugherty knows hard times from the inside. Daugherty and her brother, Jim—both brown-eyed and red-headed—grew up in the home of a West Virginia miner and factory worker. Their mother died in their early teen years. Their father drowned his grief in alcohol.Drawn close through adversity, the children found hope in their hometown church. Daugherty came to Christ through the influence of the Sunday school. Jimbo went forward in a tent meeting at age 15. Within two years, his life completely turned around; soon he was directing a local Youth for Christ group.The twosome ministered together in small-scale revival services. He preached; she played the piano or sang, and the determined duo earned their way through college. Afterwards, she went on to seminary, and Jim moved into national ministry with Youth for Christ. Daugherty set her sights on missionary work, thinking there she might find more freedom to use her gifts.Arriving in Brazil, she was struck by the pervasive poverty and quickly became involved with the women of struggling families. Their plight closely paralleled her Appalachian experience. Chuck, a son of American missionaries to Brazil, was one of Daugherty’s fellow teachers. They were married and gave birth to a daughter and son, and eventually returned to the States.Back in Charleston, West Virginia, Daugherty cared for children during the daytime, yet found spare time to teach religion courses at a local college. She quickly discovered that many pastors coming into the region were unprepared for the culture shock that comes from ministry to the rural poor. Working with local church leaders, Daugherty set up an orientation program for new pastors. But she had to abandon the classes when her college dropped its commitment to religious studies. Then, 11 years ago, the Commission on Religion in Appalachia (CORA) asked Daugherty to start a training program for individuals planning to minister in Appalachia. In 1985, the Appalachian Ministries Educational Resource Center (AMERC) in Berea was born. AMERC is a trio of hands-on experiences designed to give pastors the skills they will need to work among the chronically poor:• The January Travel Seminar, an intensive session taking students to family farms, strip-mine sites, and cooperative parish ministries.• On-site rural internships, in which students work directly in parishes.• Summer Term, a six-week program taught at Berea College, where students spend much of their time living in a community.A major reason that AMERC succeeds is Daugherty herself. Out in public, she is persuasively direct, talking about poverty without playing up sentimentality. Daugherty’s unassuming intensity is relieved by a distinctive laugh. She will, says a staffer, “rare back and let out a belly laugh” at herself and the bizarre situations that shoe-string operations frequently find themselves in. That humor helps her staff to “run but not faint.”AMERC’s mission is to strengthen church leadership in Appalachia by recruiting and training clergy and lay professionals for long-term service. Students may learn how to strengthen the churches by working with local people, how to teach in a low-literacy environment, cultivate a garden, or do canning in the church kitchen.The old Pearson Farm, donated anonymously last October, has given AMERC a campus. The farmhouse has been remodeled and its garage has been converted into a library. Typical of Daugherty’s unstinting hospitality, this winter she housed volunteer workers in her own apartment and prepared meals.In February, friends gathered to dedicate the library. The library fund is named in memory of Daugherty’s brother, who died of cancer last year.Daugherty is equally gracious and comfortable with feminists and fundamentalists. As a result, AMERC is thoroughly ecumenical—including Protestants, Roman Catholics, and the Orthodox. J. Steven Rhodes, AMERC’s associate director for academic affairs, says he treasures the memory of a monk, an IBM executive, and a snake handler washing each other’s feet at the service that ended a recent summer term.Daugherty believes the high level of cooperation has been achieved in Appalachia “because we’ve been poor longer, long enough to no longer look to big government or big business, long enough to be asking, instead, ‘How are we going to help ourselves?’ ”Governed by CORA, Berea College, and 45 sponsoring theological institutions, AMERC is now the largest cooperative alignment of seminaries in America. AMERC has trained 439 seminary grads from 37 denominations.Daugherty points out that since there are not enough big-steeple churches to go around, more than half of all seminary graduates will end up in small-town and rural pastorates. Her goal is to train them to cope so that she can successfully appeal to each to give 15 years in service among the rural poor.By then, she figures, the new influx of resources into the mountains will be under way. Meanwhile, don’t underestimate this spunky angel for Appalachia.By Harry Genet.Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture

Christopher Watkin (Zondervan Academic)

Biblical Critical Theory is an outstanding example of careful scholarship employed for the life of the church. Watkin leads the reader through a comprehensive account of the biblical narrative. At each scene in this narrative, he shows how complex biblical truths are often divided into false dichotomies or watered-down compromises. He argues, in contrast, that biblical teaching cuts across these divides and subverts cultural expectations. Watkin travels with ease from biblical exegesis to intellectual history to contemporary philosophy. Scholars, teachers, and pastors will all benefit from this work. I cannot recommend it highly enough. — Gregory E. Ganssle, professor of philosophy, Biola University

(Read an excerpt from Biblical Critical Theory, as well as an interview with the author.)

Award of Merit

Humble Confidence: A Model for Interfaith Apologetics

Benno van den Toren and Kang-San Tan (IVP Academic)

Humble Confidence offers a fresh integration of evangelism, missiology, and apologetics. With uncommon clarity and grace, the authors bring these insights to bear on the complexities of the modern world, particularly the many religious viewpoints and expressions embedded in innumerable cultural contexts. Crucially, they retain a commitment to rational defense of the Christian faith while resisting the power struggles, logic chopping, and depersonalization that often accompany apologetic efforts. What results is a holistic model of interfaith engagement that honors and respects the bodies, minds, hearts, and souls of all involved. — Marybeth Baggett, professor of English and cultural apologetics, Houston Christian University

Finalists

The Augustine Way: Retrieving a Vision for the Church’s Apologetic Witness

Joshua D. Chatraw and Mark D. Allen (Baker Academic)

Justin Brierley (Tyndale Elevate)

(Read CT’s review of The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God.)

Bible and Devotional

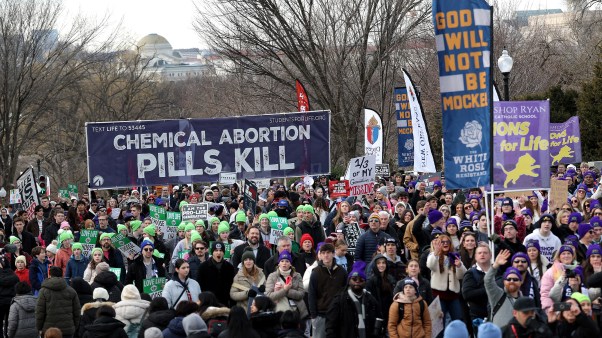

Catholics And Evangelicals In The TrenchesA recent document spells out new ways to share a foxhole in the culture wars.In 1534, Abbot Paul Bachmann published a virulent anti-Protestant booklet entitled “A Punch in the Mouth for the Lutheran Lying Wide-Gaping Throats.” Not to be outdone, the Protestant court chaplain, Jerome Rauscher, responded with a treatise of his own, entitled “One Hundred Select, Great, Shameless, Fat, Well-Swilled, Stinking, Papistical Lies.”Such was the tenor of theological discourse among many of the formative shapers of classical Protestantism and resurgent Roman Catholicism in the sixteenth century. How surprised those feisty forebears would be to learn that their “conservative” heirs, removed by five centuries and an ocean, could find so much on which to agree in the historic document released last month, “Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium.” Convened by evangelical leader Charles Colson of Prison Fellowship and Roman Catholic thinker Richard John Neuhaus of the Institute on Religion and Public Life (and a former Lutheran clergyman), a group of some 30 evangelical and Catholic representatives have proposed ways to deepen cooperation and lessen conflict between these two major faith communities. Marked by civility, candor, and conviction, their statement reflects the changing pattern of American church life over the past generation. Traditional Catholics and conservative Protestants, once bitter rivals, have become wary allies in the culture wars that so sharply divide the American people in general.For more than 30 years, a select group of American Catholics and evangelicals has stood side by side in support for parental choice in education, advocacy of the traditional values of chastity, family, and community, opposition to abortion on demand, and repudiation of pornography—all derived from deeply held religious conviction.Born of the trenchesHere is an ecumenism of the trenches born out of a common moral struggle to proclaim and embody the gospel of Jesus Christ to a culture in disarray. This is not merely a case of politics making strange bedfellows. It is more like Abraham bargaining with God for the minimal number of righteous witnesses required to spare the sinful city of Sodom.For too long, ecumenism has been left to Left-leaning Catholics and mainline Protestants. For that reason alone, evangelicals should applaud this effort and rejoice in the progress it represents. However, lest anyone be carried away by the ecumenical euphoria of the moment, it needs to be stated clearly that the Reformation was not a mistake.Both the formal and material principles of the Reformation—that is, the infallibility of Holy Scripture and justification by faith—are duly affirmed in this statement. But how these principles relate to a host of other issues such as church authority, sacramental efficacy, and authentic ministry are acknowledged points of difference. The fact that evangelicals share more in common with born-again Catholics than with liberal Protestants—on theological as well as social grounds—should not blind us to the fact that substantial and persistent differences remain between us. The framers of this document have not dodged these issues, but they must pursue them further on the basis of the commonly confessed Trinitarian and Christological consensus. Only in communities of faith where heresy is a possibility and truth has not been reduced to mere opinion can genuine theological debate take place.A time to sew, not to rendThe document’s call for universal religious liberty and world evangelization can be warmly embraced, but the plea to refrain from “proselytizing” can be affirmed only if it is understood that nominal church membership (whether Catholic or Protestant) makes no one a Christian. Personal faith in Jesus Christ as sole and sufficient Savior for all people everywhere is the message we proclaim, and no Christian can relinquish the responsibility to bear witness to that good news to anyone anywhere.For faithful evangelicals and believing Roman Catholics, this is a time to sew, not a time to rend. In expressing our common convictions about Christian faith and mission, we can do no better than to heed the words of John Calvin: “That we acknowledge no unity except in Christ; no charity of which he is not the bond, and that, therefore, the chief point in preserving charity is to maintain faith sacred and entire.”By senior editor Timothy George, dean of Beeson Divinity School, Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.What China Doesn’T NeedWhen Secretary of State Warren Christopher tried earlier this year to nudge China to ease up on its dissidents, he tried using its Most Favored Nation trade status as a bargaining chip. “No thanks,” said the Chinese. “We don’t see the connection.” They do see a connection, however, between foreigners invading their country in the name of religion, and their right to persecute the church—a connection that may have inspired last winter’s crackdown. Once again, Western Christians would do well to rethink their role in China’s Christian community.Western idealists, including church and mission leaders, somehow find it hard to believe that other countries do not accept our democratic ideals as the best deal for everyone, East or West. China’s current lapse on human rights offers fresh reminders that although they may never measure up to our ideals, God’s work in his Chinese church does not depend on the Chinese possessing something like the U.S. Bill of Rights.Whatever this latest crackdown means for China’s Christians, such decrees are just as futile as all previous attempts by Chinese Communists to rub out religion. Perhaps no other generation has seen anything like the growth of the church in China in the past quarter of a century. When the Communists took power over 45 years ago, China had about 5 million Christians (2 million Protestants and 3 million Catholics). According to current estimates, the numbers now stand at 75 million—63 million Protestants and 12 million Catholics. God gave this growth without sending foreign missionaries.At the high tide of mission work in China, before this astonishing growth, some 8,500 missionaries worked there. In one sense, the current ingathering can be attributed to the seed sown during the 140 years of missionary work. The government tried every conceivable diabolical scheme to obliterate any vestige of religion brought in by foreign missionary “devils.” Millions of Christians were among the 20 million Chinese who perished in the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). But the gospel clung to Chinese soil.Having been purified by fire, however, China’s Christians emerged with their own distinctive witness and worship. In the process, they shed the hated, shameful opprobrium that theirs was a Western religion, propped up by “subversives” from America and elsewhere. They also shed a lot of the Western scaffolding (church organizational structures, methods, and institutions, as well as buildings) that had been erected prior to 1949, scaffolding that missionaries sometimes find too painful to dismantle. God sometimes uses other kinds of pain to bring forth a more culturally legitimate expression of his church.No one expects the current government to resume its campaign to eliminate religion from China. But while scholars try to figure out what is behind the new restrictions, it would not be too far off the mark to think that one goal is to hold another missionary invasion at bay. If that is true, perhaps the government is doing the church in China a huge favor. Already we hear about consultations among missionaries on how to save China from being engulfed by the same kind of freewheeling, culturally insensitive, do-it-yourself missionary work that has stampeded into the former Soviet empire.Does a church that has grown from 2 million to 75 million need foreign missionaries? If so, what kind, how many, and what should they do? These are tough questions, especially for those of us who have allowed our missions conquests to give us something of a Messiah complex. But too much is at stake if we barrel ahead with yet another onslaught of well-meaning missionary candidates challenged to take the gospel to a country that has done a pretty good job with it themselves. Certainly China still needs some historically astute, culturally mature missionaries, but not an avalanche of aggressive greenhorns from hundreds of Western agencies.My hunch is that the future of Christian missions lies with people like the Chinese physician I met recently. He had gone to a West African nation to offer medical assistance. There he met an American surgeon who told him about Jesus. The surgeon also arranged for the Chinese doctor to come to the United States as a medical observer in a nearby hospital. Now he has been studying English at a community college so he can later study missions at a Christian college. “I want to go back to China as a missionary,” he told me.Rather than crash the gates, it is better to reflect on how God has arranged to put another Chinese missionary back in his own country through a “chance” meeting with a Christian doctor in rural Africa. No agency can come up with a better plan than that.By advisiory editor Jim Reapsome, editor of Evangelical Missions Quarterly and World Pulse Newsletter, in which parts of this editorial appeared.

Catholics And Evangelicals In The TrenchesA recent document spells out new ways to share a foxhole in the culture wars.In 1534, Abbot Paul Bachmann published a virulent anti-Protestant booklet entitled “A Punch in the Mouth for the Lutheran Lying Wide-Gaping Throats.” Not to be outdone, the Protestant court chaplain, Jerome Rauscher, responded with a treatise of his own, entitled “One Hundred Select, Great, Shameless, Fat, Well-Swilled, Stinking, Papistical Lies.”Such was the tenor of theological discourse among many of the formative shapers of classical Protestantism and resurgent Roman Catholicism in the sixteenth century. How surprised those feisty forebears would be to learn that their “conservative” heirs, removed by five centuries and an ocean, could find so much on which to agree in the historic document released last month, “Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium.” Convened by evangelical leader Charles Colson of Prison Fellowship and Roman Catholic thinker Richard John Neuhaus of the Institute on Religion and Public Life (and a former Lutheran clergyman), a group of some 30 evangelical and Catholic representatives have proposed ways to deepen cooperation and lessen conflict between these two major faith communities. Marked by civility, candor, and conviction, their statement reflects the changing pattern of American church life over the past generation. Traditional Catholics and conservative Protestants, once bitter rivals, have become wary allies in the culture wars that so sharply divide the American people in general.For more than 30 years, a select group of American Catholics and evangelicals has stood side by side in support for parental choice in education, advocacy of the traditional values of chastity, family, and community, opposition to abortion on demand, and repudiation of pornography—all derived from deeply held religious conviction.Born of the trenchesHere is an ecumenism of the trenches born out of a common moral struggle to proclaim and embody the gospel of Jesus Christ to a culture in disarray. This is not merely a case of politics making strange bedfellows. It is more like Abraham bargaining with God for the minimal number of righteous witnesses required to spare the sinful city of Sodom.For too long, ecumenism has been left to Left-leaning Catholics and mainline Protestants. For that reason alone, evangelicals should applaud this effort and rejoice in the progress it represents. However, lest anyone be carried away by the ecumenical euphoria of the moment, it needs to be stated clearly that the Reformation was not a mistake.Both the formal and material principles of the Reformation—that is, the infallibility of Holy Scripture and justification by faith—are duly affirmed in this statement. But how these principles relate to a host of other issues such as church authority, sacramental efficacy, and authentic ministry are acknowledged points of difference. The fact that evangelicals share more in common with born-again Catholics than with liberal Protestants—on theological as well as social grounds—should not blind us to the fact that substantial and persistent differences remain between us. The framers of this document have not dodged these issues, but they must pursue them further on the basis of the commonly confessed Trinitarian and Christological consensus. Only in communities of faith where heresy is a possibility and truth has not been reduced to mere opinion can genuine theological debate take place.A time to sew, not to rendThe document’s call for universal religious liberty and world evangelization can be warmly embraced, but the plea to refrain from “proselytizing” can be affirmed only if it is understood that nominal church membership (whether Catholic or Protestant) makes no one a Christian. Personal faith in Jesus Christ as sole and sufficient Savior for all people everywhere is the message we proclaim, and no Christian can relinquish the responsibility to bear witness to that good news to anyone anywhere.For faithful evangelicals and believing Roman Catholics, this is a time to sew, not a time to rend. In expressing our common convictions about Christian faith and mission, we can do no better than to heed the words of John Calvin: “That we acknowledge no unity except in Christ; no charity of which he is not the bond, and that, therefore, the chief point in preserving charity is to maintain faith sacred and entire.”By senior editor Timothy George, dean of Beeson Divinity School, Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.What China Doesn’T NeedWhen Secretary of State Warren Christopher tried earlier this year to nudge China to ease up on its dissidents, he tried using its Most Favored Nation trade status as a bargaining chip. “No thanks,” said the Chinese. “We don’t see the connection.” They do see a connection, however, between foreigners invading their country in the name of religion, and their right to persecute the church—a connection that may have inspired last winter’s crackdown. Once again, Western Christians would do well to rethink their role in China’s Christian community.Western idealists, including church and mission leaders, somehow find it hard to believe that other countries do not accept our democratic ideals as the best deal for everyone, East or West. China’s current lapse on human rights offers fresh reminders that although they may never measure up to our ideals, God’s work in his Chinese church does not depend on the Chinese possessing something like the U.S. Bill of Rights.Whatever this latest crackdown means for China’s Christians, such decrees are just as futile as all previous attempts by Chinese Communists to rub out religion. Perhaps no other generation has seen anything like the growth of the church in China in the past quarter of a century. When the Communists took power over 45 years ago, China had about 5 million Christians (2 million Protestants and 3 million Catholics). According to current estimates, the numbers now stand at 75 million—63 million Protestants and 12 million Catholics. God gave this growth without sending foreign missionaries.At the high tide of mission work in China, before this astonishing growth, some 8,500 missionaries worked there. In one sense, the current ingathering can be attributed to the seed sown during the 140 years of missionary work. The government tried every conceivable diabolical scheme to obliterate any vestige of religion brought in by foreign missionary “devils.” Millions of Christians were among the 20 million Chinese who perished in the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). But the gospel clung to Chinese soil.Having been purified by fire, however, China’s Christians emerged with their own distinctive witness and worship. In the process, they shed the hated, shameful opprobrium that theirs was a Western religion, propped up by “subversives” from America and elsewhere. They also shed a lot of the Western scaffolding (church organizational structures, methods, and institutions, as well as buildings) that had been erected prior to 1949, scaffolding that missionaries sometimes find too painful to dismantle. God sometimes uses other kinds of pain to bring forth a more culturally legitimate expression of his church.No one expects the current government to resume its campaign to eliminate religion from China. But while scholars try to figure out what is behind the new restrictions, it would not be too far off the mark to think that one goal is to hold another missionary invasion at bay. If that is true, perhaps the government is doing the church in China a huge favor. Already we hear about consultations among missionaries on how to save China from being engulfed by the same kind of freewheeling, culturally insensitive, do-it-yourself missionary work that has stampeded into the former Soviet empire.Does a church that has grown from 2 million to 75 million need foreign missionaries? If so, what kind, how many, and what should they do? These are tough questions, especially for those of us who have allowed our missions conquests to give us something of a Messiah complex. But too much is at stake if we barrel ahead with yet another onslaught of well-meaning missionary candidates challenged to take the gospel to a country that has done a pretty good job with it themselves. Certainly China still needs some historically astute, culturally mature missionaries, but not an avalanche of aggressive greenhorns from hundreds of Western agencies.My hunch is that the future of Christian missions lies with people like the Chinese physician I met recently. He had gone to a West African nation to offer medical assistance. There he met an American surgeon who told him about Jesus. The surgeon also arranged for the Chinese doctor to come to the United States as a medical observer in a nearby hospital. Now he has been studying English at a community college so he can later study missions at a Christian college. “I want to go back to China as a missionary,” he told me.Rather than crash the gates, it is better to reflect on how God has arranged to put another Chinese missionary back in his own country through a “chance” meeting with a Christian doctor in rural Africa. No agency can come up with a better plan than that.By advisiory editor Jim Reapsome, editor of Evangelical Missions Quarterly and World Pulse Newsletter, in which parts of this editorial appeared.14 Fresh Ways to Enjoy the Bible

James F. Coakley (Moody)

It’s easy to get stuck in our approaches to the Bible—reading it from a certain perspective, asking the same questions of each text, defaulting to familiar ways of interpreting it, or even just getting bored with our old routines. This book offers 14 ways to look at Scripture with fresh eyes, not only revealing meanings and emphases we may have missed but also illuminating the artistry and ingenuity of biblical authors and the Spirit who inspired them. Coakley’s explanations of each concept, as well as examples from biblical and nonbiblical works, will help readers deepen their understanding of Scripture and appreciate its literary beauty. — Chris Tiegreen, author of numerous devotional books and Bible study guides

Award of Merit

What is your definition of discrimination? These days it may depend on how steady your nerves are.At George Mason Univeristy, a guide for students defines discrimination as “jumping when a homosexual touches you on the arm.” It also includes “keeping a physical distance from someone because they are a known gay or lesbian.” Imagine campus administrators scurrying around with tape measures, unmasking the guilty who jump too high or stand too far away.Most people dismiss stories like this as the latest campus silliness—no different from the goldfish-swallowing competitions of the thirties. Others chalk it up to overly sensitive campus officials fearful of offending anyone.But political correctness is much more than sensitivity. It is a manifestation of a deep-rooted philosophical struggle, which Christians critically need to understand. Just as storms are moved by hidden upper-air currents, so cultures are steered by powerful, invisible philosophical currents. And a new current sweeping over our nation right now may alter the very character of American life.PHILOSOPHICAL FACE-OFFCollege campuses are caught in a face-off between modern Enlightenment rationalism and postmodern relativism. The Enlightenment philosophers wanted all the benefits of Christianity without belief in God. By human rationality alone they hoped to discover universal truth and universal morality.But no sooner were these ideas launched than they were shattered on the rocks of history. Each philosopher staked out his own vision of the True and the Good—only to have his stakes pulled up by succeeding philosophers offering competing visions. Finally, suspicion was cast on the very notion of rationality.Gradually it became clear that no mere mortal can stand above his limited niche in time and space to gain a completely objective, “godlike” perspective. Today the vision of human reason discovering ultimate truth on its own is dismissed as Enlightenment arrogance.But postmodernists reel to the other extreme: They deny the existence of any universal truth or morality. Postmodernism holds that individuals are merely constructs of social forces—race, gender, and ethnic background. Every cultural group has its own “truth.”Ideas are no longer judged by a standard of truth but by whether they advance a particular racial, gender, or ethnic group. African-Americans who teach that Plato and Alexander the Great were black often seem less interested in historical fact than in fostering black students’ self-esteem. Radical feminists who preach goddess worship do not seem to care whether a goddess objectively exists, they just want to “empower” women.When people stop believing in a transcendent truth, however, debates about ideas degenerate into power struggles. After all, if there is no truth, then we cannot persuade one another by rational arguments. All that is left is power: Whatever group has the most power imposes its opinions on everyone else.Lest you think I’m being alarmist, let me assure you that this is exactly what postmodernists themselves say. Stanley Fish at Duke University recently wrote There’s No Such Thing As Free Speech, supporting strict campus speech codes. Why not? Fish argues. After all, public discourse is merely a battle to protect our own preferences while restricting everyone else’s. He writes: “Someone is always going to be restricted next, and it is your job to make sure that the someone is not you.”This is frightening stuff. It’s the perfect philosophy to justify tyranny. As Wheaton College professor Roger Lundin explains in The Culture of Interpretation, in postmodernism “all principles are preferences—and only preferences.” As a result, “they are nothing but masks for the will to power.” Postmodernists even recast the Enlightenment’s sacred cows of reason and science as tools of oppression. So, feminist scholar Sandra Harding complains, science embodies a male-centered view that is “culturally coercive.”These ideas assault the very foundations of social and intellectual life. No society can survive without some shared principles, some shared vision of what moral philosophers call the Good Life. But if all principles are merely preferences imposed by force, society degenerates into a war of all against all. Campus codes prescribing how high you may jump or what words you may use are harbingers of the coercion we may soon face at all levels of society.You and I need to be aware that postmodernism is not just one more “ism” on the intellectual horizon. It has become a powerful force changing our culture. The ground rules for engaging our culture must therefore shift dramatically as well. Until recently, Christian apologetics has defended the faith against Enlightenment attacks in the name of scientific rationalism; but at least both sides were debating objective, universal truth. Postmodernism, however, has tossed out the very notion of universal truth. Today we can no longer simply defend our faith as the Truth; we must first defend the very concept of transcendent, universal truth.Christians are called to stand against the spirit of the age. But first we must identify that spirit as it changes from generation to generation. We must “understand the times,” as Paul says in Romans 13. In our own times, the good news is that the arrogance of Enlightenment rationalism is deflated. The bad news is that postmodernism retreats into an irrationalism deadly to our communal life.The PC wars are not just campus silliness. They are reflections of a battle over fundamental principles of truth and social morality, which go to the very heart and soul of our common life.

What is your definition of discrimination? These days it may depend on how steady your nerves are.At George Mason Univeristy, a guide for students defines discrimination as “jumping when a homosexual touches you on the arm.” It also includes “keeping a physical distance from someone because they are a known gay or lesbian.” Imagine campus administrators scurrying around with tape measures, unmasking the guilty who jump too high or stand too far away.Most people dismiss stories like this as the latest campus silliness—no different from the goldfish-swallowing competitions of the thirties. Others chalk it up to overly sensitive campus officials fearful of offending anyone.But political correctness is much more than sensitivity. It is a manifestation of a deep-rooted philosophical struggle, which Christians critically need to understand. Just as storms are moved by hidden upper-air currents, so cultures are steered by powerful, invisible philosophical currents. And a new current sweeping over our nation right now may alter the very character of American life.PHILOSOPHICAL FACE-OFFCollege campuses are caught in a face-off between modern Enlightenment rationalism and postmodern relativism. The Enlightenment philosophers wanted all the benefits of Christianity without belief in God. By human rationality alone they hoped to discover universal truth and universal morality.But no sooner were these ideas launched than they were shattered on the rocks of history. Each philosopher staked out his own vision of the True and the Good—only to have his stakes pulled up by succeeding philosophers offering competing visions. Finally, suspicion was cast on the very notion of rationality.Gradually it became clear that no mere mortal can stand above his limited niche in time and space to gain a completely objective, “godlike” perspective. Today the vision of human reason discovering ultimate truth on its own is dismissed as Enlightenment arrogance.But postmodernists reel to the other extreme: They deny the existence of any universal truth or morality. Postmodernism holds that individuals are merely constructs of social forces—race, gender, and ethnic background. Every cultural group has its own “truth.”Ideas are no longer judged by a standard of truth but by whether they advance a particular racial, gender, or ethnic group. African-Americans who teach that Plato and Alexander the Great were black often seem less interested in historical fact than in fostering black students’ self-esteem. Radical feminists who preach goddess worship do not seem to care whether a goddess objectively exists, they just want to “empower” women.When people stop believing in a transcendent truth, however, debates about ideas degenerate into power struggles. After all, if there is no truth, then we cannot persuade one another by rational arguments. All that is left is power: Whatever group has the most power imposes its opinions on everyone else.Lest you think I’m being alarmist, let me assure you that this is exactly what postmodernists themselves say. Stanley Fish at Duke University recently wrote There’s No Such Thing As Free Speech, supporting strict campus speech codes. Why not? Fish argues. After all, public discourse is merely a battle to protect our own preferences while restricting everyone else’s. He writes: “Someone is always going to be restricted next, and it is your job to make sure that the someone is not you.”This is frightening stuff. It’s the perfect philosophy to justify tyranny. As Wheaton College professor Roger Lundin explains in The Culture of Interpretation, in postmodernism “all principles are preferences—and only preferences.” As a result, “they are nothing but masks for the will to power.” Postmodernists even recast the Enlightenment’s sacred cows of reason and science as tools of oppression. So, feminist scholar Sandra Harding complains, science embodies a male-centered view that is “culturally coercive.”These ideas assault the very foundations of social and intellectual life. No society can survive without some shared principles, some shared vision of what moral philosophers call the Good Life. But if all principles are merely preferences imposed by force, society degenerates into a war of all against all. Campus codes prescribing how high you may jump or what words you may use are harbingers of the coercion we may soon face at all levels of society.You and I need to be aware that postmodernism is not just one more “ism” on the intellectual horizon. It has become a powerful force changing our culture. The ground rules for engaging our culture must therefore shift dramatically as well. Until recently, Christian apologetics has defended the faith against Enlightenment attacks in the name of scientific rationalism; but at least both sides were debating objective, universal truth. Postmodernism, however, has tossed out the very notion of universal truth. Today we can no longer simply defend our faith as the Truth; we must first defend the very concept of transcendent, universal truth.Christians are called to stand against the spirit of the age. But first we must identify that spirit as it changes from generation to generation. We must “understand the times,” as Paul says in Romans 13. In our own times, the good news is that the arrogance of Enlightenment rationalism is deflated. The bad news is that postmodernism retreats into an irrationalism deadly to our communal life.The PC wars are not just campus silliness. They are reflections of a battle over fundamental principles of truth and social morality, which go to the very heart and soul of our common life.The Blessed Life: A 90-Day Devotional through the Teachings and Miracles of Jesus

Kelly Minter (B&H)

Minter provides a contemplative exploration of a short period in Jesus’ earthly life. Readers walk alongside Christ’s disciples, encountering crowds, misfits, and sufferers while hanging on to the Messiah’s every word. With gracefully short and profound chapters, The Blessed Life illustrates the ongoing relevance of Jesus’ teachings and miracles for building and sustaining faith in today’s world. Minter’s powerful writing helps us receive Jesus’ words the way his original audience did—as new, fresh, and brimming with hope. — Eryn Lynum, Bible teacher, author of Rooted in Wonder

Finalists

Hearing the Message of Ecclesiastes: Questioning Faith in a Baffling World

Christopher J. H. Wright (Zondervan)

Lent: The Season of Repentance and Renewal

Esau McCaulley (InterVarsity Press)

(Read an excerpt from Lent.)

Biblical Studies

Jesus the Purifier: John’s Gospel and the Fourth Quest for the Historical Jesus

Craig L. Blomberg (Baker Academic)

Blomberg, a prominent New Testament scholar, gives a thorough account of the scholarship that has characterized four distinct “quests” to understand Jesus as a historical figure. As he highlights significant themes and trajectories, he illustrates why the Gospel of John should play a larger role in this research. Blomberg’s argument centers on the motif of Jesus as purifier, showing how—in both John and the other Gospels—he moves beyond a focus on ritual purity to speak of being cleansed and sanctified by the Holy Spirit. John’s gospel has obvious theological value; Jesus the Purifier helps us appreciate its historical value as well. — May Young, associate professor of biblical studies, Taylor University

Award of Merit

When each edition of CHRISTIANITY TODAY arrives in your mailbox, your level of interest is determined in part by the cover art: Does the image draw you in, making it hard for you to toss it aside? Our hope and goal is for you to answer yes.For the past 12 years, the person who designed those covers, who commissioned the art, called the photographers, positioned the type, has been Joan Nickerson. And her graphic signature did not end with the cover; her imprint can be seen on nearly every editorial page. Through her diligent efforts, the design of CT has remained fresh, contemporary, dignified—much like the art director herself.Despite having one of the most youthful spirits on our staff, Joan has decided to retire. This is the last issue for which she is responsible.Saying thank you does not begin to do justice to her contributions. One of the joys of working at CTi is to brush up against those who love our Lord and have been touched by him to do a mighty work. I count Joan among them. While continually raising the standards of excellence for Christian publishing, Joan has gone the extra mile by mentoring and encouraging a whole generation of Christian graphic artists. At a time when the arts were often ignored by the church, she has helped to keep the artistic flame burning.Next month the magazine in your mailbox will look a little different, as a new personality will begin to make his mark on our pages. Like Joan before him, Tom Moraitis comes to us from our sister publication CAMPUS LIFE. His goal, our hope, is to continue Joan’s vision—a high ambition.MICHAEL G. MAUDLIN, Managing Editor

When each edition of CHRISTIANITY TODAY arrives in your mailbox, your level of interest is determined in part by the cover art: Does the image draw you in, making it hard for you to toss it aside? Our hope and goal is for you to answer yes.For the past 12 years, the person who designed those covers, who commissioned the art, called the photographers, positioned the type, has been Joan Nickerson. And her graphic signature did not end with the cover; her imprint can be seen on nearly every editorial page. Through her diligent efforts, the design of CT has remained fresh, contemporary, dignified—much like the art director herself.Despite having one of the most youthful spirits on our staff, Joan has decided to retire. This is the last issue for which she is responsible.Saying thank you does not begin to do justice to her contributions. One of the joys of working at CTi is to brush up against those who love our Lord and have been touched by him to do a mighty work. I count Joan among them. While continually raising the standards of excellence for Christian publishing, Joan has gone the extra mile by mentoring and encouraging a whole generation of Christian graphic artists. At a time when the arts were often ignored by the church, she has helped to keep the artistic flame burning.Next month the magazine in your mailbox will look a little different, as a new personality will begin to make his mark on our pages. Like Joan before him, Tom Moraitis comes to us from our sister publication CAMPUS LIFE. His goal, our hope, is to continue Joan’s vision—a high ambition.MICHAEL G. MAUDLIN, Managing EditorHow to Read and Understand the Psalms

Bruce K. Waltke and Fred G. Zaspel (Crossway)

When it comes to works of biblical studies, my ideal is high-level scholarship that connects to pulpits and pews. How to Read and Understand the Psalms is a masterful example, and it now qualifies as my go-to introduction for this section of Scripture. Other introductions are often dry and remote, and even when they accurately dissect specific parts of the Psalms, they can miss the larger point, which is guiding the people of God in speaking to and worshiping God. I have spent a good bit of time working on and thinking about the Psalms, and while reading this book, I was instructed, corrected, and stirred to devotion. — Ray Van Neste, professor of biblical studies, Union University

Finalists

Nobody’s Mother: Artemis of the Ephesians in Antiquity and the New Testament

Sandra Glahn (IVP Academic)

J. Gordon McConville (Baker Academic)

Children

Holy Night and Little Star: A Story for Christmas

Mitali Perkins (WaterBrook)

This original Christmas story is told from the viewpoint of Little Star, a shy yet courageous member of the galaxy, who discovers her purpose in obedience to Maker. On Holy Night, when all the greater stars and planets join with the heavenly host in announcing the Savior’s birth, Little Star learns she has a special part to play as well. Illustrated in muted jewel tones, the brief but lyrical text reads almost like a lullaby. And when Little Star recognizes Maker in the manger, the young reader also learns that “everything was different now, but Maker was the same. Today, tomorrow, forever.” — Pamela Kennedy, children’s author, cocreator of the Otter B series

Award of Merit

Jacques Ellul, who contributed a legacy of social analysis and prophetic theology matched by few in the twentieth century, died May 19 at his home in Pessac, France. Ellul, troubled by heart problems and other ailments in recent years, died near the University of Bordeaux, where he served as professor of the History and Sociology of Institutions in the Faculty of Law and Economic Sciences from 1946 to 1980.He is best known for his critical analysis of the impact of technology on modern life—not just by the introduction of various machines but, more profoundly, by subtly changing methods of thinking and values. In a technical milieu, rationality, measurable effectiveness, quantification, and standardization are replacing God, goodness, tradition, eccentricity, and the like at a great human and spiritual cost. This social analysis unfolded in more than 30 volumes, the best known of which is The Technological Society, which passed the 100,000 mark in sales.Ellul, 82, also had been an active lay theologian in the Reformed Church of France. He wrote on biblical topics, Christian ethics, and the relationship of the church to the world. His books include The Presence of the Kingdom, The Meaning of the City and The Ethics of Freedom. Ellul’s work drew on the Bible, Kierkegaard, and Barth, and challenged Christendom, which he viewed as being too conformed to this world.Ellul’s legacy is impressive for its sheer size, scope, depth, and breadth. He engaged the political Left and Right, Marxists and capitalists, religious and nonreligious, theological liberals and conservatives.The theologian’s life was distinguished by its combination of activism and thought. He was fired from his first university post for protesting the Nazi occupation of Vichy France. He worked in the French Resistance and helped Jews escape the Nazis during World War II. His positions on the technological threat, political inutility, strategic anarchism, and theological universalism caused some to summarily reject his work. Others, however, found his work a brilliant challenge to rethink some of their major assumptions and conclusions, even if they did not agree with all his proposals.By David W. Gill.

Jacques Ellul, who contributed a legacy of social analysis and prophetic theology matched by few in the twentieth century, died May 19 at his home in Pessac, France. Ellul, troubled by heart problems and other ailments in recent years, died near the University of Bordeaux, where he served as professor of the History and Sociology of Institutions in the Faculty of Law and Economic Sciences from 1946 to 1980.He is best known for his critical analysis of the impact of technology on modern life—not just by the introduction of various machines but, more profoundly, by subtly changing methods of thinking and values. In a technical milieu, rationality, measurable effectiveness, quantification, and standardization are replacing God, goodness, tradition, eccentricity, and the like at a great human and spiritual cost. This social analysis unfolded in more than 30 volumes, the best known of which is The Technological Society, which passed the 100,000 mark in sales.Ellul, 82, also had been an active lay theologian in the Reformed Church of France. He wrote on biblical topics, Christian ethics, and the relationship of the church to the world. His books include The Presence of the Kingdom, The Meaning of the City and The Ethics of Freedom. Ellul’s work drew on the Bible, Kierkegaard, and Barth, and challenged Christendom, which he viewed as being too conformed to this world.Ellul’s legacy is impressive for its sheer size, scope, depth, and breadth. He engaged the political Left and Right, Marxists and capitalists, religious and nonreligious, theological liberals and conservatives.The theologian’s life was distinguished by its combination of activism and thought. He was fired from his first university post for protesting the Nazi occupation of Vichy France. He worked in the French Resistance and helped Jews escape the Nazis during World War II. His positions on the technological threat, political inutility, strategic anarchism, and theological universalism caused some to summarily reject his work. Others, however, found his work a brilliant challenge to rethink some of their major assumptions and conclusions, even if they did not agree with all his proposals.By David W. Gill.The Things God Made: Explore God’s Creation through the Bible, Science, and Art

Andy McGuire (Zonderkidz)

The story of creation is ubiquitous enough that one might wonder if we need yet another children’s book on the topic. But wonder was, in fact, the word that came to mind as I read The Things God Made. Complemented beautifully by breathtaking artwork, the book has captured the staggering awe that the story of our fascinatingly intricate creation deserves. If we have lost our sense of wonder, McGuire aims to rekindle it. Brilliantly infusing expertise with humility, scientific fact with childlike joy, The Things God Made is a delight. I suspect it will lead readers—children and adults alike—one step beyond wonder and straight into worship. — Hannah C. Hall, children’s writer, author of God Bless You and Good Night

Finalists

Good Night, Body: Finding Calm from Head to Toe

Brittany Winn Lee (Tommy Nelson)

Marvel at the Moon: 90 Devotions

Levi Lusko (Tommy Nelson)

Young Adults

Heather Holleman (Moody)

This Seat’s Saved captures the longing of every teenager in America: belonging. Elita, like so many girls her age, finds herself in a state of friendship adversity. Suddenly, she is excluded from the lunch table by her best friend with the painful statement “This seat’s saved.” Feeling abandoned, she battles fear and loneliness. But in a world that screams at her to fit in, Elita learns that lasting joy comes not from earning the best seat at the lunch table but from receiving the seat God has freely given her next to Christ. — Reese Carlson, youth pastor, author of Church Doesn’t End With Z

Award of Merit

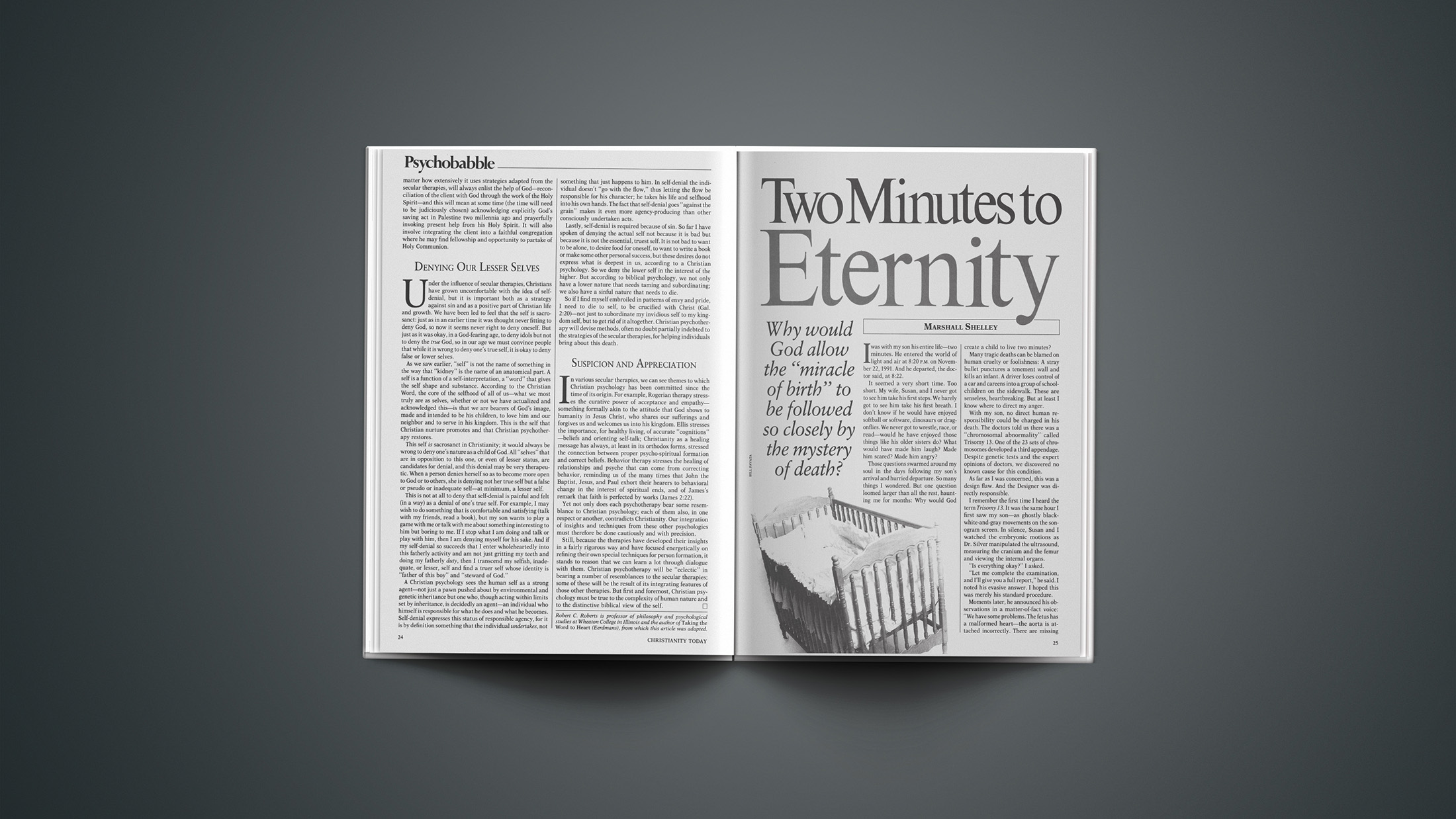

I was with my son his entire life. Two minutes.

He entered the world of light and air at 8:20 p.m. on November 22, 1991. And he departed, the doctor said, at 8:22.

It seemed a very short time. Too short. My wife, Susan, and I never got to see him take his first steps. We barely got to see him take his first breath.

I don't know if he would have enjoyed softball or software, dinosaurs or dragonflies, machines or math. We never got to wrestle, race, or read—would he have enjoyed those things like his older sisters do? What would have made him laugh? Made him scared? Made him angry?

Those questions swarmed around my soul in the days following my son's arrival and all-too-hurried departure. So many things I wondered. But one question loomed larger than all the rest, haunting me for months: Why would God create a child to live two minutes?

Many tragic deaths can be blamed on human cruelty or foolishness. A stray bullet punctures a tenement wall and kills an infant. A driver loses control of a car and careens into a group of schoolchildren on the sidewalk. Senseless. Heartbreaking. But at least I know where to direct my anger.

With my son, no direct human responsibility could be charged in his death. It was a "chromosomal abnormality" called Trisomy 13. One of the 23 sets of chromosomes developed a third appendage. Despite genetic tests and the expert opinions of doctors, we discovered no known cause for this condition.

As far as I was concerned, this was a design flaw. And the Designer was directly responsible.

I remember the first time I heard the term "Trisomy 13." It was the same hour I first saw my son—as ghostly black-white-and-gray movements on the sonogram screen. In silence, Susan and I watched the embryonic motions as Dr. Silver manipulated the ultrasound, measuring the cranium and the femur and viewing the internal organs.

"Is everything okay?" I asked.

"Let me complete the examination, and I'll give you a full report," he said. I noted his evasive answer and hoped this was merely his standard procedure.

Moments later, he announced his observations in a matter-of-fact voice: "We have some problems. The fetus has a malformed heart—the aorta is attached incorrectly. There are missing portions of the cerebellum. A club foot. A cleft palate and perhaps a cleft lip. Possibly spina bifida. This is probably a case of Trisomy 13 or Trisomy 18. In either case, it is a condition incompatible with life."

Neither Susan nor I could say anything. So Dr. Silver continued.

"It's likely the fetus will spontaneously miscarry. If the child is born, it will not survive long outside the womb. You need to decide if you want to try to carry this pregnancy to term."

We both knew what he was asking. I was speechless. Susan found her voice first. Though shaken by the news, she said softly but clearly, "We believe God is the giver and taker of life. If the only opportunity I have to know this child is in my womb, I don't want to cut that time short. If the only world he is to know is the womb, I want that world to be as safe as I can make it."

We left the medical center that July afternoon stunned and saddened.

"Pregnancy is hard enough when you know you're going to leave the hospital with a baby," Susan said. "I don't know how I can go through the pain of childbirth knowing I won't have a child to hold."

Signs of the Pneuma

Summer turned to fall, and we were praying that our son would be healed. And if a long life were not God's intention for him, we prayed that he could at least experience the breath of life. We longed see that reminder of God's Spirit, the Pneuma, flow through him like a gentle wind.

Even that request seemed in jeopardy as labor began November 22. As the contractions got more severe, signs of fetal distress caused the nurses to ask, "Should we try to deliver the baby alive?"

"Yes, if at all possible, short of surgery," Susan replied.

They kept repositioning Susan and gave her oxygen, and the fetal distress eased.

And then suddenly the baby was out. The doctor cut the cord and gently placed him on Susan's chest. He was a healthy pink, and we saw his chest rise and fall. The breath of life. Thank you, God.

Then, almost immediately, he began to turn blue. We stroked his face and whispered words of welcome, of love, of farewell. And all too soon the doctor said, "He's gone."

Within minutes, our pastor, our parents, and our children came into the room. Together we wept, held one another, and took turns holding our son. My chest ached from heaviness. Death is enormous, immense, unstoppable.

The loss was crushing, but mingled with the tears and the terrible pain was something else. I'm not sure I can describe it.

At the births of my three older daughters, I'd felt "the miracle of birth," that sacred moment when a new life enters the world of light and air. The pneuma, the breath of life, fills the lungs for the first time. Now this moment was doubly intense because the miracle of birth was followed so quickly by the mystery of death. The pneuma was here and now gone.

"It feels like eternity just intersected earth" was all I could say to our pastor. The pain of grief was diminished not at all, but it blended with the weight of overwhelming wonder at the irresistible movement from time to eternity.

"Do you have a name for the baby?" asked one of the nurses.

"Toby," Susan said. "It's short for a biblical name, Tobiah, which means 'God is good.' "

We had long thought about the name for this child. We didn't particularly feel God's goodness at that moment. The name was what we believed, not what we felt. It was what we wanted to feel again someday.

The words of C.S. Lewis, describing the lion Aslan, kept coming to mind: "He's not a tame lion. But he's good." We clung to that image of untamed and fearsome goodness, even as we continued to struggle with the question: Why would God create a child to live two minutes?

Everything Has an Inside

Shortly before we discovered Toby's condition, I read a book by Christopher de Vinck, The Power of the Powerless, in which he describes what he learned from his severely and profoundly retarded brother, Oliver.

I was interested because our third daughter, Mandy, was also severely retarded, unable to respond to her environment. And just three months after Toby's birth and death, Mandy also entered eternity. She was two weeks shy of her second birthday. One of the points de Vinck made about Oliver helped me with the God-directed questions I had after Toby's birth and death.

One of the greatest discoveries that a child or an adult can make, writes de Vinck, is that "everything has an inside. In our house, we split apples to look at the core, we crack walnuts to see the meat inside, we press a toy stethoscope to our chests to listen to the heartbeat."

The point: you can't always guess what's on the inside by looking at the outside.

The Bible says that "Man looks on the outward appearance, but God looks on the heart." That was true then. It's true now. We're so outer focused. We're taught to judge people by the stylishness of their clothing labels. Political campaigns are crafted by scriptwriters, TV directors, and pollsters. Educational policies are based on appearances of political correctness. We're tempted to believe that image is everything, that outward appearances are most important. We ignore the inside, the heart, the spirit.

Each of my children also has an inside. With my two older girls, I get occasional glimpses of their interior life. Their words and actions give me clues about their inner worlds. With Mandy, the glass was darker. And with Toby, we never had a chance to see inside.

But Mandy and Toby both had insides. Despite the damage to the outer frame, the inside is to be treasured.

Our Unearthly Calling

Not long after we buried Toby and Mandy, our seven-year-old daughter, Stacey, told us she heard God's voice in the middle of the night telling her that "Mandy and Toby are very busy. They are building our house, and they are guarding his throne."

Not knowing how to respond to a child who had never offered a claim like that before, I found myself reading the Bible with renewed interest in descriptions of heavenly activities. Was this message consistent with Scripture? Our family discussions usually focused on heaven.

We saw that heaven is a place of activity, not just leisure or ease. God is preparing a city for the faithful (Heb. 11:16), where all will be made perfect and complete (Heb. 11:40). The Bible contains many descriptions of heavenly worship as active and intense.

And since Jesus said that in his Father's house are "many mansions" and he was going to prepare a place for us (John 14), we could easily envision part of our heavenly activity being to help prepare for those yet to arrive.

I must admit, however, that I was more intrigued by the image of guarding Christ's throne. Was this an honor guard? A ceremonial assemblage of children, whom Christ on earth had invited to be near him? Or perhaps seats of honor for those Christ had in mind when he said, "The last shall be first"? I can't think of many more "last" than Mandy and Toby.

But what if guarding the throne isn't ceremonial but actual? Daniel 10 describes the angel Michael in conflict with a spiritual foe. Ephesians 6:12 describes a struggle "against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms." Could it be that among the spiritual warriors in this conflict is one named Toby?

The Book of Revelation records battles involving heavenly armies (Rev. 19:19). Could it be that along with countless others of us, Toby will serve among the heavenly hosts in that final great war?

All of this, of course, is conjecture. But what is clear is that heaven will be a place of active duty.

And when the ultimate spiritual battle is over, our responsibilities continue.

The apostle John's vision of eternity suggests what's in store for all the saints: "The throne of God and of the Lamb will be in the city, and his servants will serve him. They will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads …. And they will reign forever and ever" (Rev. 22:3-5).

I don't know exactly what our service in that city will involve, nor can I be specific about how we will assist in reigning. But those tasks sound like they may have a bit more significance than most careers we pursue in our current lifetime.

Could it be that when I finally start the most significant service of my life, I'll find that this is what I was truly created for? I may find that the reason I was created was not for anything I accomplish on earth, but the role I'm to fulfill forever.

I realized that my earlier question had been answered.

Why did God create a child to live two minutes?

He didn't.

He didn't create Toby to live two minutes or Mandy to live two years. He didn't create me to live 40 years (or whatever number he may choose to extend my days in this world).

God created Toby for eternity. He created each of us for eternity, where we may be surprised to find our true calling, which always seemed just out of reach here on earth.

Knowing God’s Truth: An Introduction to Systematic Theology

Jon Nielson (Crossway)

It’s a huge challenge to write a systematic theology book for teens in language they can understand. But Nielson succeeds at this task, helping students grasp deep concepts like eschatology and soteriology. Each chapter contains a Scripture passage that students are encouraged to memorize, as well as pauses where they are invited to pray and reflect on how theological truths can transform their hearts and lives. Nielson does a fine job explaining differing positions on topics like baptism and the end times while leaving space for students to think for themselves. — Jennifer M. Kvamme, student ministries catalyst at Centennial Evangelical Free Church in Forest Lake, Minnesota, author of More to the Story: Deep Answers to Real Questions on Attraction, Identity, and Relationships

Finalists

Do Not Be True to Yourself: Countercultural Advice for the Rest of Your Life

Kevin DeYoung (Crossway)

Hotel Oscar Mike Echo: A Novel

Linda MacKillop (B&H Kids)

Christian Living/Spiritual Formation