When he published his scandalous guide for picking up women in ancient Rome in A.D. 2, the elegiac poet Ovid recommended gladiatorial shows as a great location for finding love. Something about watching men fight to the death, Ovid suggested, just works.

Ovid’s casual acceptance of violence as a source of respectable public entertainment was nothing new. Rather, it was the norm in pre-Christian antiquity. A little over 400 years before Ovid, for example, the anonymous author of The Constitution of the Athenians complained about what he considered to be one of Athens’s greatest social ills: On Athenian streets, he sputtered, a man can’t easily tell which passersby he could strike at will. Slaves, he thought, needed more distinctive clothes so you’d know that you could hit them.

I could keep going, but you get the point: The ancient world was defined by its acceptance of pervasive violence. True, some ancients bemoaned this status quo, but they had no expectation that it would ever change.

So why are we not like this today? The answer, in a nutshell, is 2,000 years of Christianity. The change Christianity made in bringing compassion and mercy to a world that defaulted to cruelty is so complete that it is difficult for modern American Christians to fathom. We take our norms around violence for granted, but we shouldn’t. They are uniquely Christian—and uniquely worth preserving.

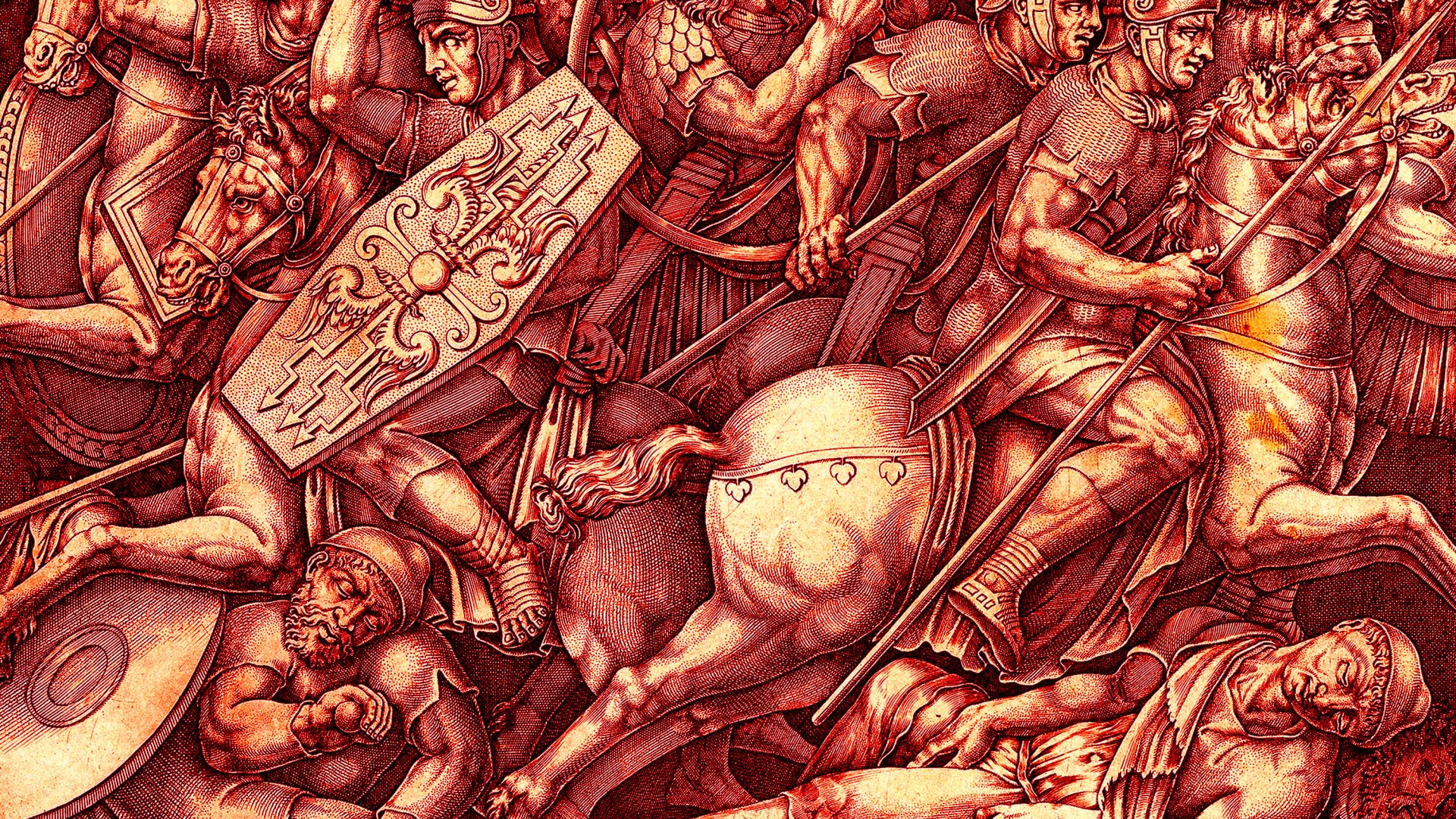

This difference between Christian and pagan thought is most clearly visible in how we treat civilians in war, and one of our best sources to understand the contrast is none other than Julius Caesar. Throughout the ’50s B.C., Caesar was Rome’s leading military general, campaigning in Gaul. His official aim was to subdue the territory and make it safe for a full Roman takeover.

But Caesar also felt his career was stagnating, and he needed a goodwill boost from the Roman public. What should a man in such a quandary do before the age of social media? In a useful reminder that TikTok isn’t necessary for documenting atrocities, Caesar wrote about his military victories in vicious and graphic detail, publishing in installments back home in Rome what would become known as Gallic War.

If you’ve ever wondered what good Christianity ever did for our violent, war-torn world, Caesar’s text—well in line with other military writings that survive from the Greco-Roman Mediterranean—gives a visceral answer.

In one striking episode, Caesar’s army comes across a large group of Germanic refugees who had been driven out of their former home by another tribe. It seems clear from Caesar’s description that these are not trained soldiers—they are unarmed families. To the surprise of the crowd, Caesar responds to the meeting by ordering a full-scale military attack.

A massacre ensues as Caesar’s soldiers pursue defenseless men, women, and children on land and to the nearby river, where some jump into the water in a vain attempt to escape. Caesar happily boasts that this “battle” resulted in not a single Roman casualty though the enemy numbered 430,000. Caesar does not provide a precise number for casualties, but modern archaeological findings at the site confirm the gist of the account: 150,000 civilians dead.

Even that lower number far exceeds the 5,000-enemy death toll Rome considered to be the baseline for a general to claim a triumph—the highest military honor available to a Roman. In other words, the slaughter had no military justification, even by the laws of the day. It was senseless cruelty, the result of the utter devaluing of the lives of non-Romans, and it was only one of several such episodes Caesar thought would make for good PR.

We read a story like that and easily call it genocide. But scholars including Michael Kulikowski and Tristan Taylor argue that no one among Caesar’s original audiences batted an eye over these descriptions of violence. His popularity in Rome increased. Our horror in reading Caesar’s text, in other words, is distinctly ours—the product of 2,000 years of Christian teaching about the unconditional preciousness of human life.

Christianity provided a radical and unprecedented alternative to Caesar and his world. Even the just war tradition, problematic though it is, is rooted in a very different way of thought than the pre-Christian worldview offered. Instead of allowing empires to abuse people at will, just war theory predicated standards that must be met for war to be considered justified. And our very discontent with that tradition is itself an example of the Christianization of our thinking.

Central to this change is Christianity’s revolutionary emphasis on the imago Dei (Gen. 1:27). While this idea was important in early Judaism, it was through Christianity’s adoption of the concept and rapid spread around the Mediterranean that it became widely known. Christians affirmed the priceless worth of every person in God’s eyes. But in the pagan worldview within which Caesar operated, the worth of a life depended on a number of subjective factors—including the opinion of an attacking general.

Indeed, just as in The Constitution of the Athenians, people in the Roman world fell into one of two categories: those who could not be harmed without penalty, and those who could be harmed basically at will. Roman citizens, especially men, and especially aristocratic men, fell into the former category. Non-citizens, and especially slaves, fell into the latter.

This is the significance, for instance, of Paul emphasizing his Roman citizenship on a number of occasions in his ministry (e.g., Acts 16:38): It placed him in a privileged class, and he used that to the gospel’s advantage. But the early Christians saw such distinctions as null and void. God loves every image-bearer—man or woman, slave or free, Roman citizen or not (Gal. 3:28). It is because of this different worldview that a noblewoman and her slave, new converts both, could die together as martyrs for their faith.

Even in increasingly post-Christian societies, the Christian stance on the value of human life still shapes our views of war. It is the source of our horror over violence against civilians and the foundation of formal protections for civilian life like the Geneva Conventions. It is because of Christianity that we feel outrage mixed with sorrow and horror when we see deliberate and cruel targeting of civilians, like that done by Caesar against defenseless Gaul—or the murder and sexual violence by Hamas against Israeli civilians in October, or Putin’s missile strikes against Ukrainian civilians over the past two years.

History shows that Christians have never perfectly lived our confessed belief in the imago Dei. A stumbling block for my Jewish mother, for example, has been that some professing Christians helped perpetrate the Holocaust—in her birthplace, Ukraine, Christians sometimes turned their Jewish neighbors over to the Nazis. We could also mention the Crusades and many other violent evils. Church history includes plenty of blood.

But history also shows the sheer horror of a world without the moral vocabulary to recognize those evils, without the influence of the imago Dei and the rest of the Christian worldview. It shows the horror of a world guided by Caesar, not Christ.

Nadya Williams is the author of Cultural Christians in the Early Church (Zondervan Academic, 2023) and the forthcoming Mothers, Children, and the Body Politic: Ancient Christianity and the Recovery of Human Dignity (IVP Academic, 2024).