Westminster Abbey in London, the exclusive chapel of the British royal family, has served as the site for the coronation of generations of kings, royal weddings, funerals, and other significant events. Today it functions as the final resting place for many renowned British nobles, poets, generals, scientists, and writers, such as Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, and Charles Dickens.

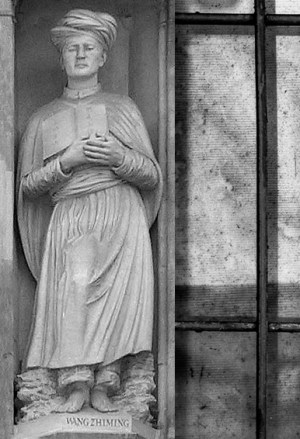

Since 1998, ten statues of 20th-century Christian martyrs from around the globe have graced the Great West Door of the abbey, including Maximilian Kolbe, Martin Luther King Jr., and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Also among these revered figures, however, is a less widely known martyr from China: Wang Zhiming (王志明, 1907–1973), a Miao pastor from Wuding County, Yunnan Province, who was persecuted during the Chinese Cultural Revolution and executed after a violent denunciation rally in 1973.

The Miao people of China first encountered the gospel when Catholicism was introduced to the Guizhou and Sichuan provinces around 1798. One hundred years later (in 1906), Protestant missionaries Arthur Nicholls (葛秀峰) and William Theophilus Simpkin (师明庆) of the China Inland Mission (CIM) journeyed for several days from Kunming to reach the Miao tribes, who were still practicing slash-and-burn agriculture and hunting.

The foreign Protestant missionaries brought not only the Bible and the gospel but also health education measures, transforming the Miao people’s old customs of ghost worship and cohabitation with animals and treating epidemics such as plague and typhoid. Samuel Pollard (伯格里), a British Methodist missionary who had come to this area before Nicholls and Simpkin, created the Miao script, translated the Bible into the Miao language, and implemented social reforms in medicine, education, charity, and infrastructure among the Miao in Guizhou.

Wang Zhiming was born in 1907 in a Miao family. From 1913 to 1924, he attended a Christian school run by CIM in Dajing and Shapushan for the local Miao people. After graduation, he accepted a teaching position at the church school. In 1940, Wang became a preacher at the Shapushan General Assembly of CIM in northern Yunnan, and in 1944, he was promoted to the position of president of the General Assembly, overseeing Miao churches in Wuding, Luquan, Fumin, Lufeng, and Yuanmou counties.

In 1945, Wang traveled to Kunming to translate and compile the Miao version of Hymns of Praise to the Lord, which may have been the first Miao hymnbook in China. By the time of the Communist takeover in 1949, there were more than 5,500 Miao, Yi, and Lisu people who believed in Christ in Wuding County alone.

In 1951, Wang was ordained by CIM in Kunming and promoted to pastor. By this time, the Communist Party had targeted Christianity as the vanguard of imperialism invading China, and foreign missionaries were rushing out of the country. Wang was accused of being a “time bomb left by imperialism in the local area,” and his ordination as a pastor became one of his crimes. In 1954, he was arrested on the charge of “not repenting and continuing to engage in religious espionage activities.”

Two years later, in an attempt at international propaganda, the Communist Party released Wang and appointed him as deputy leader of a delegation that attended the National Day ceremony in Beijing, where he was received by Mao Zedong. However, this was merely an attempt to make Wang a tool for the Three-Self Patriotic Movement. Wang’s faith in Christ did not waver.

At this time, the Miao church had entered the stage of self-governance, self-support, and self-propagation. With the deepening land reform efforts and the political campaigns of the Great Leap Forward and the Socialist Education Movement, the church faced increasing persecution. Church properties were seized, and pastors were arrested, tortured, and imprisoned.

By the time of the Cultural Revolution, the movement emphasizing the personal worship of Mao Zedong and loyalty to his ideology had reached its peak. Public church activities were completely banned, and the church went underground. Wang was constantly a target for refusing to let the Communist Party mold him into a “new socialist person.” Instead, he led his followers in clandestine Christian gatherings in nearby caves.

On May 11, 1969, Wang, along with 20 other church leaders, was arrested for opposing believers’ participation in the “Three Loyalties” (to Mao) campaign. Wang was accused of five “crimes.” First, he was called an imperialist lackey and an unrepentant spy, disseminating a spiritual opium (religion) that dulled the masses. Second, he was labeled a counterrevolutionary. Third, he was said to have consistently resisted the state’s religious policy. Fourth, he was a landlord, one of the “Five Black Categories”; and fifth, during the Long March, when the Red Army passed through Lufeng County, he had led a group of landlords who obstructed the Red Army’s passage, even personally killing Red Army soldiers (this last claim of murder was a false accusation).

During his incarceration in the Wuding County Detention Center from 1969 to 1973, Wang endured extreme mental and physical tribulations. When confronted with the question, “Do you trust Mao Zedong or Jesus?” his unequivocal response was “I believe in Jesus.” Wang’s refusal to recant exposed him to horrific torture.

In 1973, Wang sensed that his day of martyrdom for the Lord was imminent. Shackled in handcuffs and leg irons, he finally saw his son and wife, who had come to visit him. The Han guards, however, strictly forbade them to use the Miao language to communicate. Wang uttered a few words in Mandarin with coded spiritual meanings:

I have failed to reform, and my current predicament is self-inflicted. You should not emulate me but should obey the arrangements from above. You should work hard to ensure that you have food to eat and clothes to wear. You should maintain hygiene in all aspects to keep your body healthy and avoid diseases.

Wang’s wife presented him with six boiled eggs. With his bleeding palms, Wang patted his wife’s shoulders and back from left to right and then from top to bottom, making the sign of the cross in blood. He kept three of the eggs and returned three to his wife. The eggs symbolized resurrection to eternal life, and the two sets of three symbolized the Trinity.

On December 28, 1973, 66-year-old Wang was sentenced to death. The following day, after a public trial attended by tens of thousands of people at a middle school playground in Wuding County, he was paraded through the streets. His five crimes were inscribed into the death mark hat on the back of his neck, and the three Chinese characters for Wang Zhiming were crossed out in red signifying that the criminal deserved death. Wang faced the congregation with a smile on his face, showing not fear but joy.

After Wang was executed by firing squad, the local government announced that “at the request of the revolutionary masses, the criminal’s body should be completely destroyed with explosives.” Wang’s family quickly pleaded with the government for mercy, promising not to erect a tombstone or any other conspicuous marker. The government agreed to let the family “drag the body of the counterrevolutionary back home.” Villagers drove a horse-drawn cart to the execution ground to collect the body, and along the way, the Miao villagers halted the cart to bid farewell to Wang.

In 1976, Wang’s son, Wang Zisheng, was also arrested for assembling an underground church. Overall, seven members of Wang’s family suffered for their faith during the Cultural Revolution. Not until after the revolution had ended did Wang’s family receive a “rehabilitation” notice restoring his public respectability.

Illustration by CT / Source Image: WikiMedia Commons

Illustration by CT / Source Image: WikiMedia CommonsWhen Westminster Abbey decided to commemorate Wang with a statue, his descendants learned about it very late. The British had sent all the materials in English, and Wang Zisheng, the son of a “Five Black Categories” father who had never attended middle school, could not decipher the English text. But through other people’s translations and explanations, the family eventually learned that Wang had been selected as one of the most significant martyrs of the 20th century.

Around 2002, Wang’s descendants visited Westminster Abbey and took photos to bring back home. When they showed the photos in their home village, the Miao people were moved to tears and the Christians gave glory to the Lord.

In 2011, Chinese dissident writer Liao Yiwu, living in exile in Germany, published a book titled God Is Red (the English translation was published in 2012), which included Liao’s interview with Wang Zisheng and recounted some of Wang Zhiming’s stories. In 2014, independent documentary filmmaker Hu Jie released Songs from Maidichong (video in Chinese); the film recreated the heavenly praise songs echoing in the mountains of central Yunnan and described the impact of increased materialism, which had accompanied China’s “reform and opening up” period, on the Miao church. It also included interviews with Wang’s relatives.

Despite brutal persecution, Miao believers clung firmly to their faith, and their pastor, Wang Zhiming, left a poignant testimony of martyrdom. May their testimony continue to inspire the Chinese churches currently enduring persecution, and may it encourage the Miao church to take up its cross, follow the Lord, and spread the gospel faithfully in the new era.

Liu Yanzi is a Chinese scholar and teacher in Japan. She holds a PhD in international cultural studies from Kobe University.