This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

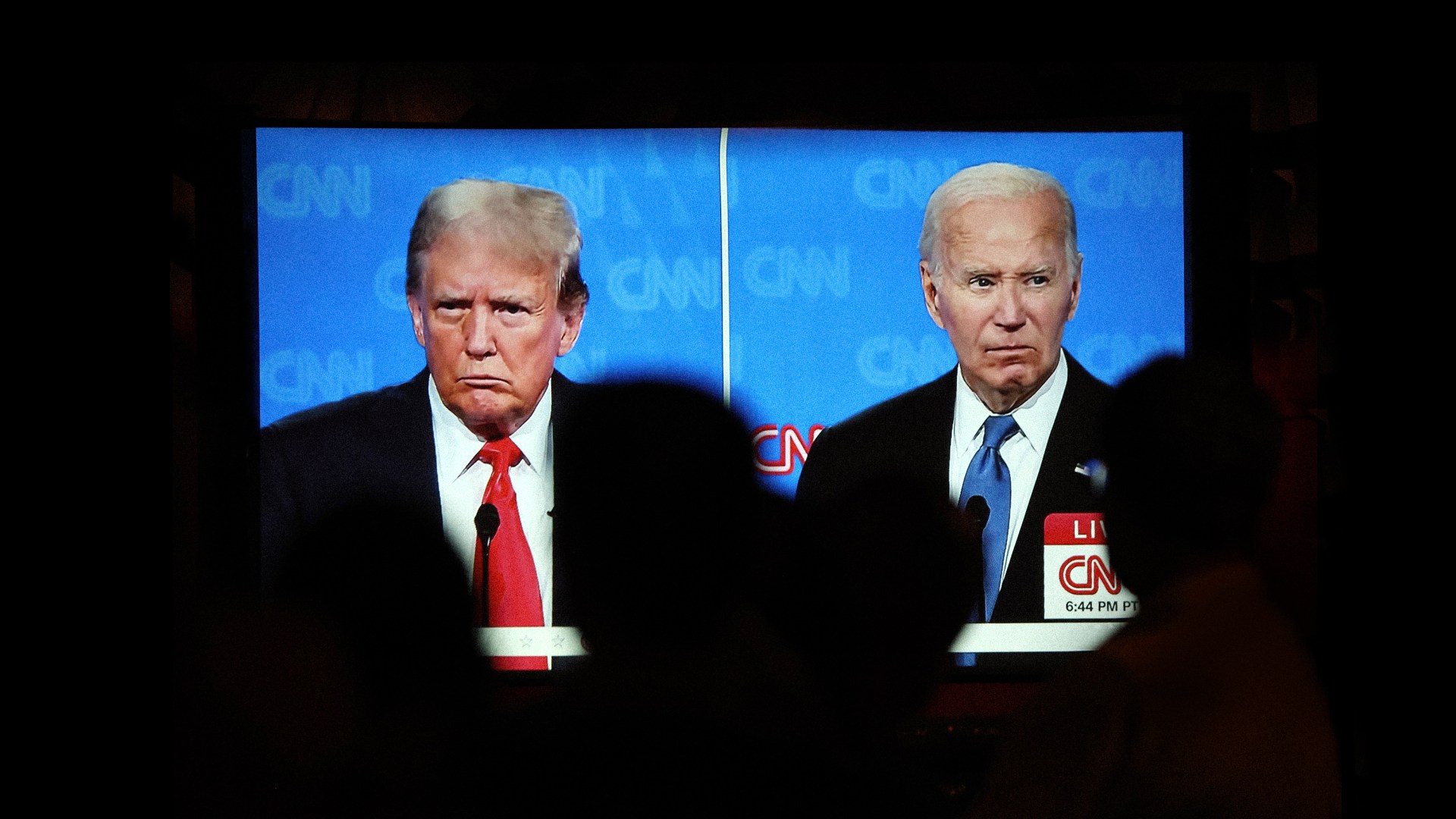

A friend of mine told me that he was at a long-planned gathering of half Republicans and half Democrats for the purpose of talking through partisan polarization. They watched the presidential debate together, and everyone was nervous that the respectful disagreements would devolve into the cheering and booing of team sports. He said it was actually the most unifying two hours of the entire meeting, because everyone was feeling the same thing: embarrassment.

No matter whether Team Red or Team Blue, the viewers recognized that our presidents once said things like, “We have nothing to fear but fear itself” and “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” Two weeks ago, from two 80-year-old men, one of whom is to lead the country for the next four years, we heard instead such lines as “I didn’t have sex with a porn star” and “Anyway … we finally beat … Medicare.” That was before they incoherently bickered about their respective golf handicaps.

When we ask, “Is this the best we can do?” we actually all know the answer. But neither man will step away, and there are no grownups that can make them.

This would be bad enough if it were only about which octogenarian will be occupying the only assisted living center in the world with a press office and a Situation Room. But the fact that our elderly leaders—one struggling to put sentences together, the other ranting with insanities and profanities—won’t leave the scene is about more than an election year. It’s about what it means to live in an era of diminished expectations.

For years, sociologists and philosophers have warned us about the dangers of a cult of youth, that behind all of the Botox treatments and cosmetic Ozempic regimens, there’s a more fundamental denial of death. We want to put aging out of sight because we don’t want to be reminded that it’s the way we will all one day go. That this is, at least when it comes to the presidency, no country for anything but old men, would seem to indicate that we’ve moved past that infatuation with youth. But the opposite is actually the case.

We live in a moment of a paradoxical juvenile gerontocracy. Never have our leaders held on with such stubbornness to the quest for power well after they have the cognitive or physical abilities to do so. And never have our leaders seemed so childish. How can both be true?

Communications theorist Neil Postman warned us that we were entering this era over 40 years ago. Children find their way in the world, he said, through wonderment. Curiosity leads to questions, and questions lead the quest to find answers. “But wonderment happens largely in a situation where the child’s world is separate from the adult world, where children must seek entry, through their questions, into the adult world,” Postman wrote. “As media merge the two worlds, as the tension created by secrets to be unraveled is diminished, the calculus of wonderment changes.”

“Curiosity is replaced by cynicism, or even worse, arrogance,” Postman continues. “We are left with children who rely not on authoritative adults but on news from nowhere. We are left with children who are given answers to questions they never asked. We are left, in short, without children.”

Keep in mind, Postman was worried about television and was writing long before the internet and social media era. At first glance, the digital era would seem to have given us the opposite problem. Jonathan Haidt, for instance, argues compellingly that one reason for the spike in anxiety among children and adolescents is the anxiety of their parents, an anxiety that leads to a smothering, overly protective parenting.

In reality, though, the “helicopter parenting” that Haidt and others describe is precisely the problem about which Postman warned, just from the other end. Parents are anxious, at least in part, because they feel scared and unequipped, with few models for to how to transition themselves into a different phase of life while preparing the next generation to take the helm.

The symbol of our age is less that of the wise old leader, giving the offertory prayer at the Sunday morning service or presenting the trophy to the young winners of the Pinewood Derby, and more that of the Margaritaville-themed retirement home filled with oldsters pretending to be right back in their teenage years, complete with the latest gossip about who has a crush on whom.

Probably every one of us knows the crushing feeling that comes with realizing that a mentor or a role model isn’t who we thought. Most of us have come close-up enough to realize that someone we thought could guide us with wisdom and maturity is actually a slave to temper, pride, ambition, lust, or greed. To some degree, that’s always been the case. T. S. Eliot wrote in the middle of the last century:

What was to be the value of the long looked forward to,

Long hoped for calm, the autumnal serenity

And the wisdom of age? Had they deceived us

Or deceived themselves, the quiet-voiced elders,

Bequeathing us merely a receipt for deceit?

At this point, though, our culture seems especially riddled through with this realization that those we thought were grownups are old, exhausted, and childish. An obviously declining president refuses to live in a world where “Hail to the Chief” is played for a new generation of leaders. The rest of the country looks to a porn-star-chasing former reality television host who says he wants to terminate the Constitution and put his enemies through televised military tribunals—and the country just laughs and enjoys the show.

We can’t do much about the cultural situation of 2024. We can, though, resolve to see and to embody a different model. The Bible upends the combination of childishness and age denial that we see all around us. Instead, the Scriptures give us the mirror-image paradox: a people who are both childlike and mature.

Jesus said that only those who become as little children will inherit the kingdom of God (Matt. 18:3; Mark 10:15). This is not, though, about childishness. Inheritance is not a pile of stuff but a stewardship, a responsibility, a vocation for grownups who have learned from, as Paul put it, “guardians and managers” (Gal. 4:1–7, ESV throughout).

The Bible gives us a glimpse of the childlike maturity paradigm at the beginning of the life of Solomon. The new king asked God for wisdom, saying, “I am but a little child. I do not know how to go out or come in” (1 Kings 3:7). He knew he was dependent. That wisdom manifested itself in the kind of maturity that knew how to not please himself but to govern a “great people” (v. 9). That didn’t last, of course. Solomon veered off to the immaturity of being governed by his appetites rather than by wisdom, and his kingdom came tumbling down.

We can thank God that Jesus tells us, “Behold, something greater than Solomon is here” (Matt. 12:42). We can walk in that way and embody it in our churches if we reject the kind of childishness that clings to power and the kind of childishness that sees power itself as a game. We can model the sort of maturity that cultivates character and equips the next generation with the hopes that they will outpace us when they do.

Our childish old-culture is embarrassing. We see it not only on a debate stage in our country but in church after church that’s segregated by age, pulpit by pulpit where the options seem to be either staying too long or being replaced by youth for the sake of youth itself. There’s a different way. There are no grownups coming to save us. We were supposed to be them.

Russell Moore is the editor in chief at Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.