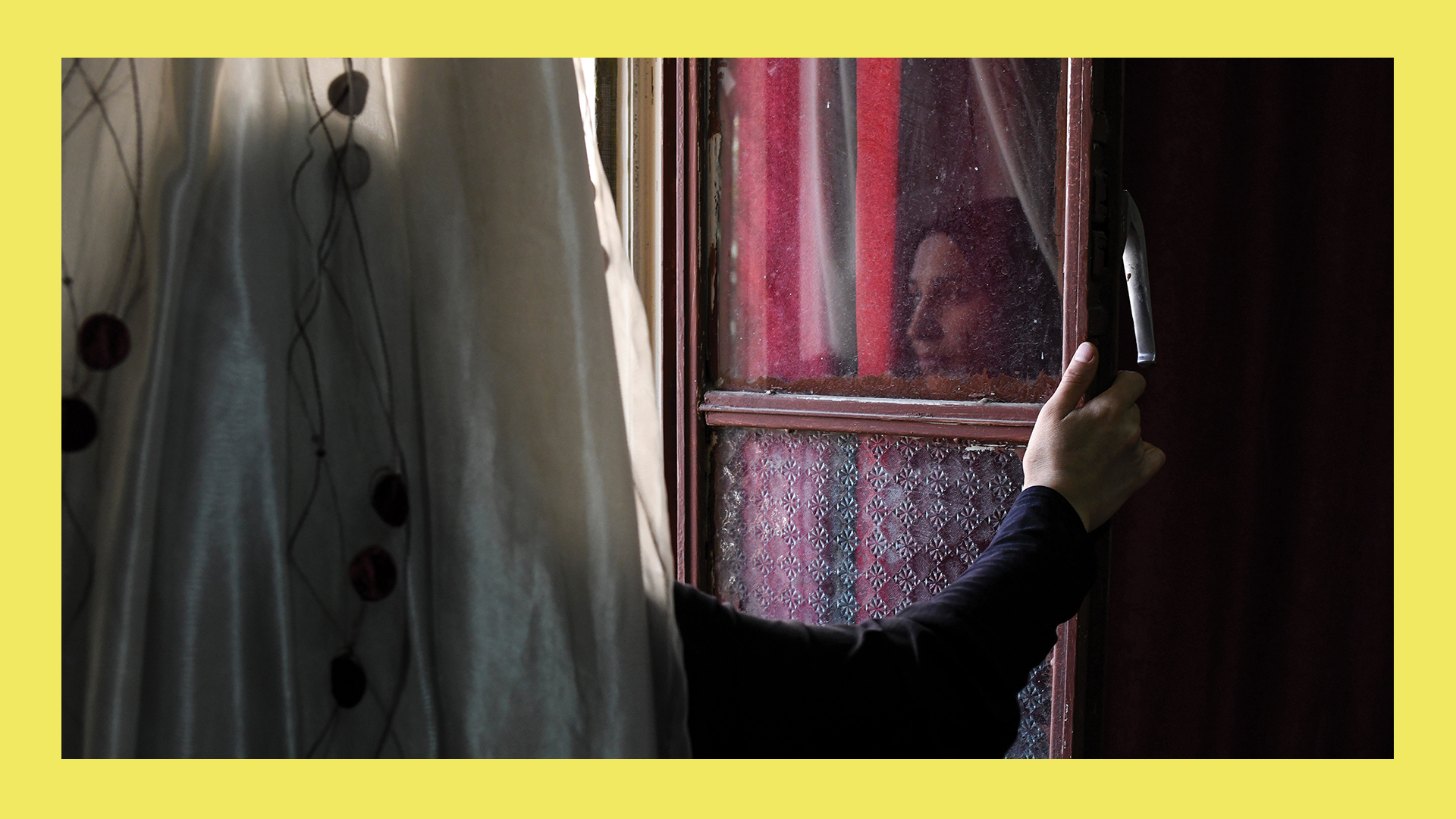

Lama Marwan Alhazzouri lived with her husband and young sons in Homs before the war in Syria began in 2011. She had never left the city, Syria’s third largest, where she grew up and married at 17.

With its wide boulevards and tree-lined neighborhoods, Homs bustled with business, an oil refinery, and agricultural production. Sunni and Alawite Muslims, Orthodox and Catholic Christians—diverse groups lived in adjoining enclaves, their ancient mosques and churches dominating the skyline.

Lama had no reason to venture elsewhere. Her parents, grandparents, and older sister Shatha Marwan Alhazzouri, all lived nearby. Her husband, Tarek Fouzi Masharka, worked a 10-minute walk away. Almost every afternoon she walked to see her parents. She even did it in heels, she recalled with a grin, her dangly gold earrings winking on both sides of her face.

Now she lives in Jordan. She wears shoes like a man, she joked, to navigate its hilly streets—a commentary on how the war changed everything.

Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia BseisoLama and her relatives fled Syria in 2012 to settle in Marka, a district in east Amman, the capital of Jordan. Known in ancient times as the “city of seven hills,” Amman now spans 19 hills. Its population of more than 4 million is roughly quadruple that of Homs. Yet Lama acclimated easily to life in Jordan at first, adjusting to the topography, the Jordanians’ Arabic accent, and new customs. With her parents living next door and her sister upstairs, she didn’t feel like a stranger in this strange land. The family spent Fridays together as they always had, with Lama’s mother cooking for everyone.

But then the war stretched from months to years, and then to more than a decade. Lama’s daily life began to shift. More than a million Syrians took refuge in Jordan, testing public services and housing. With tens of thousands of war victims from Iraq already in Amman, resentment among Jordanians simmered. Refugees crowded stores and pushed up prices.

At the same time, Lama’s close-knit family, now refugees at the mercy of international dictates, began to scatter. First her brothers Ihsan and Husam left. Ihsan immigrated to Washington State while Husam and his wife were allowed to resettle in Canada.

Next, Lama’s sister Shatha, along with her husband and their then-five daughters, moved to California.

Other relatives found sanctuary in Lebanon and Sweden. When Lama’s parents, approved for resettlement by the UN Refugee Agency, moved to Washington State in 2022, it was the final blow.

“When my siblings left, I hated [Jordan],” Lama said. “I hated it so much.” Only she and her sister Nuha remain in Marka.

“This isn’t called spreading out, it’s called ruin,” Shatha said, her black headscarf emphasizing the fierce expression in her thickly mascaraed eyes.

“When you take a family and break it up like this, that’s not dispersion—it’s destruction.”

Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia Bseiso Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia Bseiso Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia Bseiso Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia BseisoShatha is now an American citizen. In late 2022, she returned to Jordan for five weeks to visit her sisters, savoring her last hours with Lama and Nuha before parting again. Over glasses of sweetened verbena tea and bowls of mixed nuts, they reminisced about their life in Homs, their flight to Jordan, and their challenges as refugees.

The family fled Homs early in the Syrian conflict, before rebel forces there were squelched by Bashar al-Assad’s regime. At first, Lama didn’t want to leave Homs to shelter in Damascus. Even when they decided to leave, she and her relatives thought their stay in the Syrian capital would be temporary. But after 10 days in hotels converted into temporary housing, they learned the road to Homs had become blocked by explosions. Assad’s army was takng men of military age by force. Lama’s husband was in danger of conscription, so crossing the border to Jordan became their next best option.

Gradually, in small groups, the family twisted their way toward safety by way of Dara’a, staying some days in border camps before trickling into Jordan and finally to Marka.

The situation in Jordan is bad, Tarek said. “There’s no aid—not from the UNHCR, not from the UN,” he said, using the acronym for the UN Refugee Agency. “And there’s no work. If you want to get a work permit, you have to pay monthly to social security … and if you don’t have work … how are you going to pay that?”

Tarek has not been able to work, so Lama’s two oldest sons, both in their late teens, dropped out of school to help support the family. The boys slouched quietly on the living room’s periphery, listening to the adults’ conversation.

Finding steady work is not the only challenge for Syrian refugees in Jordan. Many families are saddled with niggling paperwork issues—whether byproducts of mismanagement, bureaucracy, or blatant corruption, no one really knows. Nuha’s husband, Mohamad, cannot get official refugee status, and also cannot return to his homeland.

Maysoon, another marooned relative, lives alone in the apartment below Lama. As a single adult she has her own refugee file with the UN. Because of this, she was left behind when her family members were resettled. Her parents and siblings are now in Canada, France, Sweden, and the United States. Without the presence of a father, brother, or husband in a society that values male protection, she finds herself particularly vulnerable.

Lama believes humanitarian organizations receive plenty of financial aid but do not distribute it equitably. Some families receive rent supplements, while theirs has ended. Some families are resettled together, yet theirs has been scattered. “There’s no justice,” Shatha and Lama said over and over.

Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia BseisoWhere Lama’s family found support, surprisingly, was at a local church. Christians from Marka Church visited them multiple times. They forged a friendship with a church member living in their neighborhood. When the family first arrived, teams from Marka Church delivered heaters, blankets, and mattresses. They brought staples like oil, rice, sugar, bulgur wheat, tomatoes, and mortadella. Lama’s family also participated in Marka’s fruit and vegetable voucher program, which partners with a local produce shop.

The Nazarene church sits a block off Marka’s main thoroughfare, a street that rides a ridge of hills, shuttling commuters in grimy white buses and green-tagged public transport vehicles between Jordan’s two largest cities, Amman and Zarqa. Restaurants, clothing and accessory stores, banks, pharmacies, and cell phone providers line the congested boulevard. On either side lie Marka’s residential buildings, limestone-faced apartments surrounded by olive trees and rows of scrappy cypress.

Though Christians comprise only 3 percent of Jordan’s population—about 250,000–400,000 of more than 11 million—the Jordanian church pulls disproportionate weight in caring for the needs of close to 1.5 million Syrian and Iraqi refugees. Among evangelical churches in particular, Marka Church has led with creativity and innovation since 2004, when its pastors began outreach to refugees from the Iraq War.

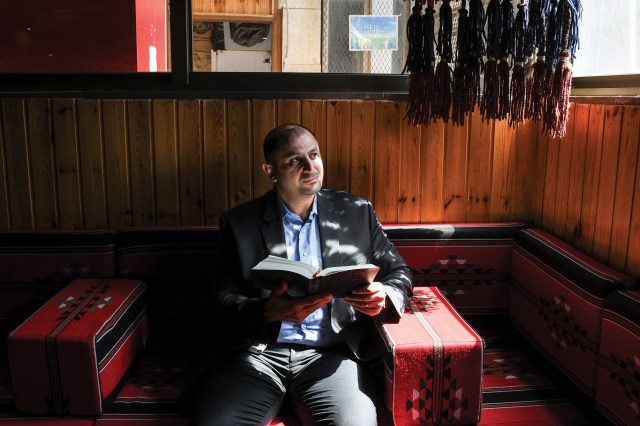

The overarching goal of Marka Church is mercy and truth meeting together, said Pastor Haytham Mazahreh, quoting Psalm 85:10. The church recently launched an aid organization, Sense of Community, which serves as an umbrella over a variety of mercy ministries meeting physical needs in the community.

A permanent clinic operates on the main church building’s third floor, staffed by general practitioners, eye doctors, dentists, and physical therapists. They serve anyone in need—Iraqi, Syrian, Palestinian, Jordanian, or other. Across the street, Good Shepherd Center provides education for around 130 Iraqi Christian children, who are unable to study in local schools. Handcraft workshops around the church’s campus supply vocational training and income to mainly Iraqi refugees.

Mercy flows beyond Marka Church’s walls as well. Pastor Ibrahim Nassar and another leader, Intesar Mazahreh, served for years with the church’s neighborhood visiting team—a vital component of ministry in a region where home visits form the foundation of social interaction.

“This is an opportunity to care for [refugees], comfort them, even without giving them anything,” Ibrahim said. “It makes a difference—it makes a difference that someone is asking about them.”

Ibrahim also pastors Church of Glory, an Assemblies of God congregation nextdoor. With his soft voice, salt-and-pepper scruff, and bushy eyebrows, he greets refugees like an eloquent, Spirit-filled bear. The Syrian conflict, coinciding with the rise of Islamic State militancy in Iraq and Syria, sent fresh waves of the persecuted to Jordan. Pastor Haytham invited Ibrahim to join Marka’s visiting team.

Intesar Mazahreh, a petite woman whose first name in Arabic means “victory,” joined the visiting team in 2015 after having a dream about serving refugees. Five mornings a week, she and others met for prayer, Bible study, and worship before breaking into small groups to visit two or three households each. These visits involved listening to people’s stories, encouraging them, and praying for them.

Initially the church also supplied a variety of household needs, she explained.

“When they came, they could hardly rent unfurnished apartments—without anything, gas, heaters, cushions, nothing—this is how their needs were,” she said. When their needs were greater, she added, “they liked to listen more to the words about Christ and about peace and love and mercy.”

Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia Bseiso Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia Bseiso Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia Bseiso Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia Bseiso Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia Bseiso Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia Bseiso Photo by Nadia Bseiso

Photo by Nadia BseisoBarred from legal employment in Jordan, Iraqi refugees struggle to settle in Marka. Many Syrians, on the other hand, have been in the country for nearly a decade. Though they still face financial challenges, they have become like Jordanians in many ways, more self-sufficient and networked within the community. As refugees’ needs change, the visiting team’s work morphs. Currently, church visits focus more on sharing the Word and discipling believers.

The seeds of love planted by the visiting teams help soften local attitudes toward the evangelical church, too. Everyone from Syrian Muslims to Iraqi Christians—usually from Orthodox and Catholic backgrounds—have been helped by Marka Church. Suspicion and fear melt away when confronted with unconditional love.

“Those people stood with us,” one refugee said. “Those people have love. Those are the people who visited us—nobody asked about us except them.”

Lama and her family also praise the help they received from the church. They miss the early visits of Marka teams and make do with less and less aid, as other crises, regional and global, take precedence over the plight of trapped Syrians. Their crisis has gone on for so long, Lama said, “the world has gotten bored.”

Last year, as a winter storm dropped flurries of snow and canceled three days of school, Lama set laundry to dry on racks around her apartment. “The days have all become like each other now,” she said, sitting beside a softly whooshing kerosene heater.

In spite of the time difference, Lama talks with her mother in Washington State every day, with Shatha in California, and with her brother in Canada. (In April 2024, Lama’s father died; she never saw him again in person.)

Sometimes she recalls their Fridays together before their dispersion—mornings with fattet hummus for breakfast, afternoons with stuffed vegetables, kubbeh, or grape leaves made by her mother.

After Shatha visited Lama in Jordan, she returned safely to the United States in January 2023, packing Middle Eastern bread and carrots in her suitcase as a taste of home. The cooked carrots made her husband happy, she said. Shatha talks now about Welcome Corps, the then newly launched US State Department program allowing Americans to privately sponsor refugee families for resettlement. Could Welcome Corps help bring Lama and Nuha to the United States? Could American churches help them the way Marka Church helped them in Jordan?

Until then, she waits—for a successful way to bring her sister to America and to reunite, at last, what remains of her family.

Esther Kline, a pen name, is an American writer living in Amman, Jordan.