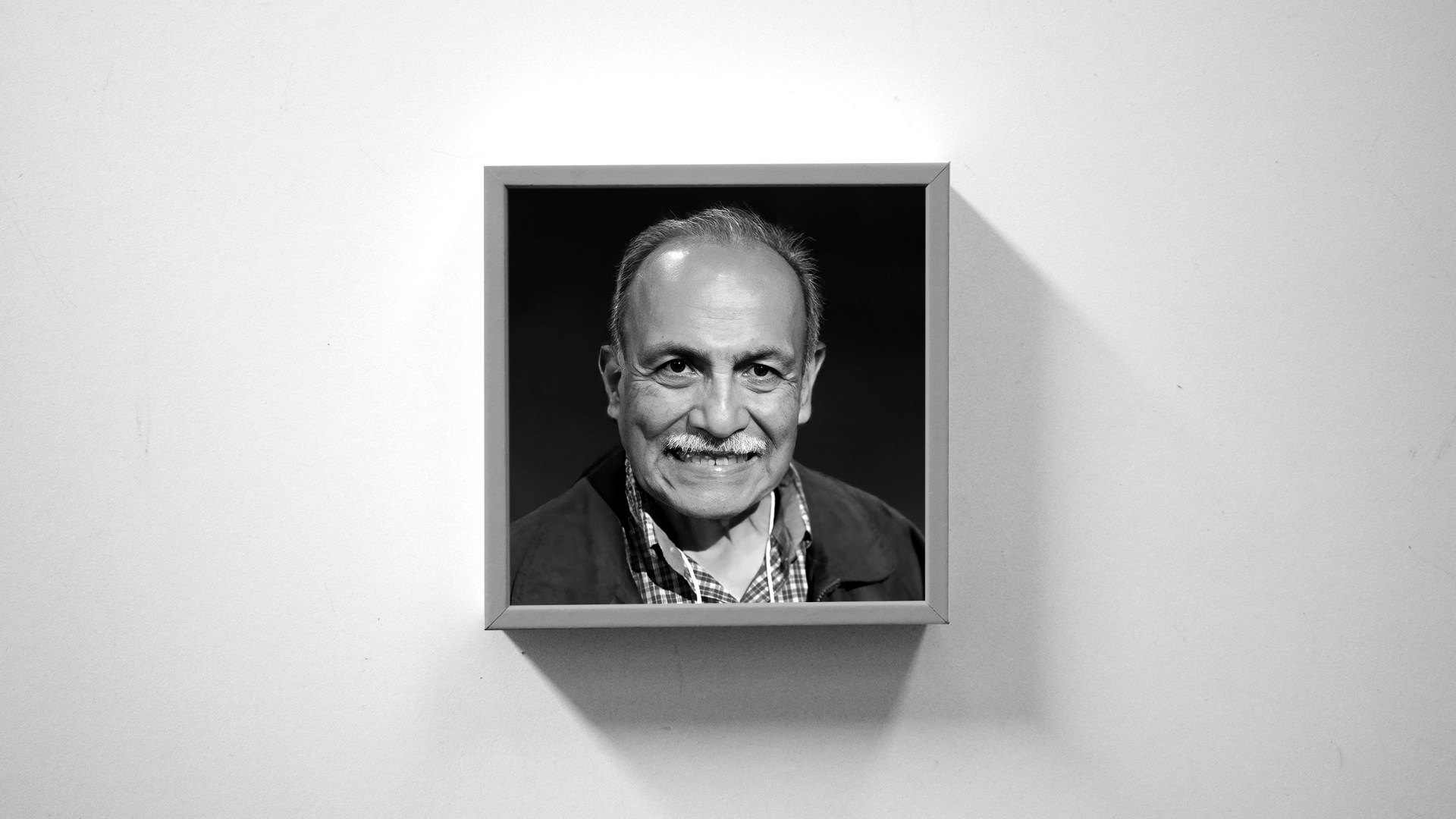

Samuel Escobar, a Peruvian pastor and theologian whose passion for social justice and evangelization resulted in a new field in missiology died on April 29 in Valencia, Spain. He was 90.

In 1970, Escobar and fellow Latin American theologians René Padilla, Orlando Costas, and Pedro Arana coined the term misión integral to refer to a theological vision that sees evangelism and social justice as inseparable components of Christian life. They saw this principle as a way to apply the evangelical faith to the injustices they saw, highlighting that care for the poor was at the center of Jesus’ message.

At the inaugural Lausanne Congress in 1974, Escobar gave a plenary address to more than 2,000 Christian leaders from 150 countries, arguing that the church had a responsibility to address the poverty and deprivation affecting its most vulnerable members.

“The way of Christ is that of service,” he said in a speech that quoted Matthew 20:27 (“Whoever wants to be first must be your slave”) and John 20:21 (“As the Father has sent me, I am sending you”).

Escobar was born in Arequipa, a city in southern Peru, in 1934. His parents became Protestants shortly before they had him, despite the fact that the country was almost entirely Catholic. Escobar’s father was a police officer, and when he and his wife separated, their son went to live with her. Escobar attended a missionary-run primary school and later was one of only two Protestants among 500 students at his public high school in Arequipa.

A young man who “devoured books and wrote poems,” Escobar entered the school of arts and literature at the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos in Lima in 1951. That same year, American Southern Baptist missionary M. David Oates baptized Escobar at the Iglesia Bautista Ebenezer de Miraflores in Lima. Later, from 1979 to 1984, Escobar served as the church’s pastor. In 1958, he married Lily Artola, whom he had met at church.

After graduating with a degree in pedagogy in 1957, Escobar began serving as the Latin American traveling secretary with the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students (IFES). As part of this work, Escobar engaged young people who had been heavily influenced by leftist ideology, which had spread across Latin America since the Russian Revolution in 1917 and gained renewed strength after the Cuban Revolution in 1959.

“Marxism was a powerful ideology on campuses, and extreme poverty, military dictatorships, and oppression of the poor made its message relevant,” he wrote.

Escobar often visited Latin American universities, giving lectures on evangelism and missions before opening up the space for questions.

“Marxists would come, not only to refute me, but also to use the occasion for proclamation of their message,” he said. “Evangelical students were surprised that it was possible to debate the Marxists and present the Gospel as a valid alternative.”

In 1967, Escobar published Diálogo Entre Cristo y Marx (Dialogue Between Christ and Marx), a compilation of these lectures. At an evangelistic campaign later that year, the event organizers distributed 10,000 copies to attendees.

Despite the hunger for dialogue, “in the evangelical atmosphere in which I grew up in Peru in the 1950s, a distinctive mark of a bona fide Evangelical was that he or she did not believe in or practice dialogue,” Escobar wrote.

Nevertheless, Escobar “studied hard and prepared himself to speak to Marxist students in a way that made sense to them, with a concern that was both social and evangelistic,” said Brazilian theologian Valdir Steuernagel, who met Escobar while a student in Argentina in 1972.

“Engaging in dialogue with others about the path that led them to Christ can be a valuable first step in understanding how we can be a help—and not a hindrance—on the journey of many others to whom Christ wants to reach,” Escobar later wrote in his book Evangelizar Hoy (Evangelize Today).

As Escobar connected with students, his country was in the midst of significant change. Peru was under a period of political unrest, with coups d’état in 1962 and 1968.

The country was also in the middle of significant internal migration. In 1950, 59 percent of all Peruvians lived in the Andes mountains (today the same amount of the population lives on the coast) on land largely owned by a small number of elites. Tired of poverty and oppression, many peasants began moving to coastal cities, where they suffered in slums, enduring exploitation they had tried to escape.

Witnessing this, Escobar and his Latin American counterparts—Padilla, Costas, and Arana—developed misión integral, their way of contextualizing their evangelical faith to the injustices they saw. (The four men also founded Fraternidad Teológica Latinoamericana, an organization which continues to promote contextualized Latin American theology.) The new convictions also drew on liberation theology, which Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez had developed as a Catholic response to the suffering he had observed.

In their keynotes at Lausanne 1974, Padilla and Escobar introduced the global church to their conviction that evangelism and social action went hand in hand. In response, many conservative church leaders labeled integral mission as Marxist or leftist. Harold Lindsell, one of the founding members of Fuller Theological Seminary, wrote for Christianity Today that “Escobar seemed to be saying that socialism is preferable to capitalism and that many Latin Americans espouse Marxism because of its emphasis on justice.”

Escobar never embraced Marxism. But his decision to teach his Christian students how to fight Marxist ideas with the Bible and theology disturbed even his IFES colleagues, who did not understand why he would be open to dialogue with these groups.

Escobar also realized that his passion for political discussions didn’t resonate with everyone and that the wave of Marxism among students would not last forever. While giving a lecture in Mexico in 1973, Escobar listened as a student said his generation had rejected changing the world via Marxist formulas and instead was turning to hallucinogens. “What does Christ have to say about this?” he asked. Startled, Escobar shared Jesus’ promise of abundant life and explained to him the futility of religious experience without faith in Christ.

Escobar stayed attuned to his local context no matter his geography. Escobar moved, late in his life, to Spain. After observing the Catholic church’s decline and the rise of postmodernism, he applauded when a local ministry published an illustrated edition of the Book of Ecclesiastes as an evangelistic tool.

“A change in methodology will not be enough. What is required is a change of spirit that consists of recovering the priorities of the person of Jesus himself,” he wrote in 1999 in Tiempo de Misión: América Latina y la Misión Cristiana Hoy. The titles of some of his works communicated his belief in the constant need for change, including the 1995 book Evangelizar Hoy (Evangelize Today), the 1982 article “Qué Significa Ser Evangélico Hoy” (What It Means to Be an Evangelical Today), or the 2016 article “Mission Fields on the Move.”

“During the twentieth century the word missionary in Peru was reserved for blond-haired, blue-eyed British or American Christians who had crossed the sea to bring the gospel to the mysterious land of the Incas,” he wrote in 2003 in A Time for Mission: The Challenge for Global Christianity. “Today there is a growing number of Peruvian mestizos—dark-eyed, brown-skinned, mixed-race Latin Americans—sent as missionaries to the vast highlands and jungles of Peru as well as to Europe, Africa and Asia.”

Escobar was always looking to bring “answers to the political, economic, and social realities of his context,” said Ruth Padilla DeBorst, theologian and daughter of Escobar’s close friend René Padilla.

Yet Escobar’s ideas of misión integral continue to shape Lausanne’s current work—and spark debate.

“He demonstrated that our faith is not a faith that alienates itself, that hides itself, that refuses to talk,” said Steuernagel. “On the contrary, he used every opportunity to share his testimony. And he did so with grace and steadfastness, something so important in these polarized and angry times.”

Escobar served as honorary president of IFES and the president of American Society of Missiology and lived in Peru, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, the United States, and Spain. In Canada, he served as general director of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship for that country. In the US, he taught at Calvin College from 1983 to 1985 and at Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Philadelphia as successor to his old friend Costas from 1985 until 2005.

In 2001, the American Baptist Churches USA’s missions arm asked Escobar to help the local denomination in Spain grow its theological education program. For the next four years, he split time between Eastern Seminary and Valencia, where his daughter, also named Lily, was living.

In 2004, Lily, his wife, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and Escobar and his daughter became her primary caretakers until she died in 2015. Escobar is survived by his daughter, Lily, his son, Alejandro, and three grandchildren.

Primera Iglesia Evangélica Bautista de Valencia, where Escobar worshiped, will host his memorial service on Friday, May 2.