This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

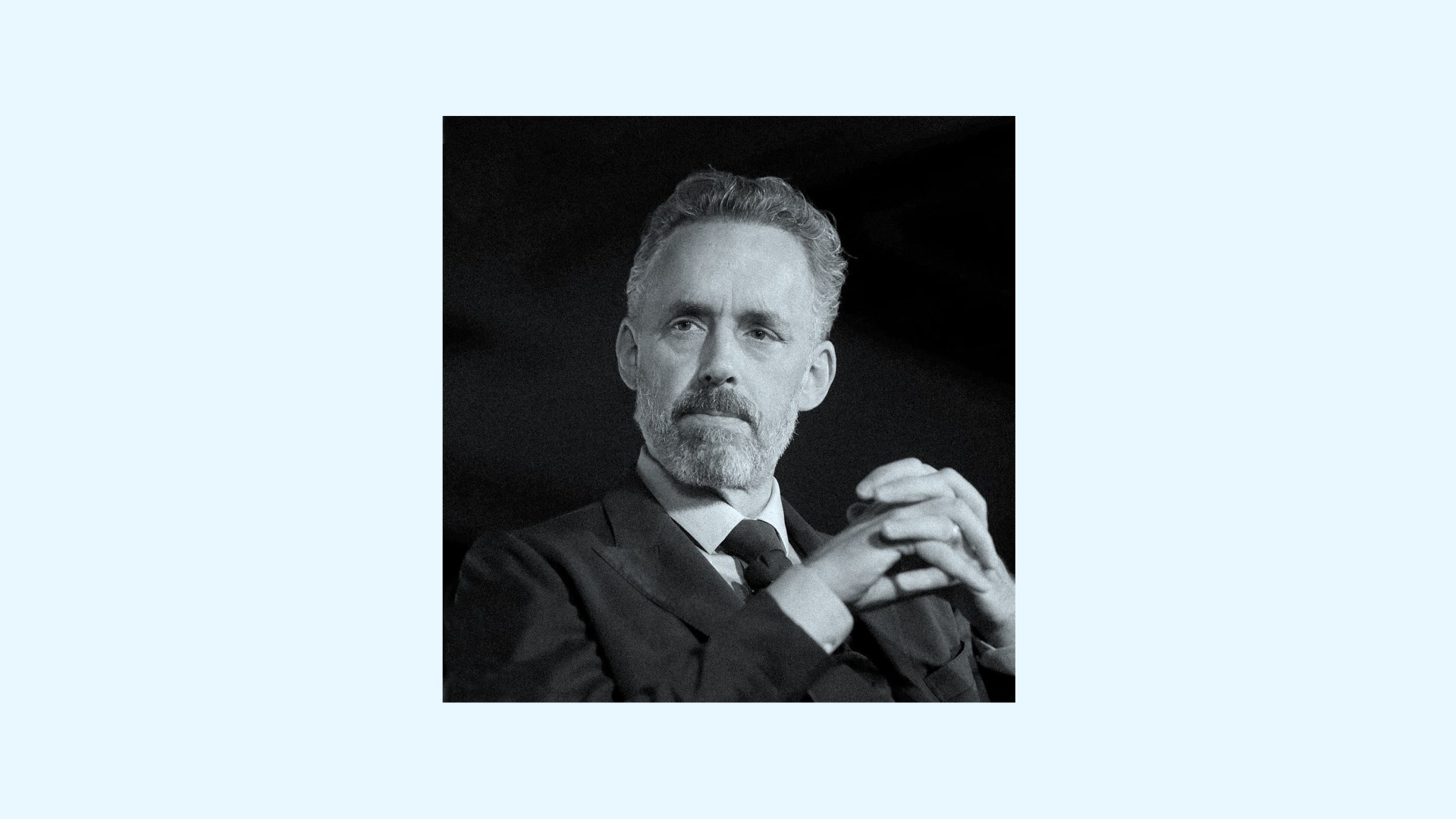

In a room full of atheists, psychologist and political pundit Jordan Peterson sat in the center seat. He was asked a single, simple question: “Are you a Christian?” His response: “You say that. I haven’t claimed that.”

This is the viral video pinging around social media accounts, puzzling both believers and skeptics. Peterson was further asked the question “Do you believe in God?” He said he wouldn’t say.

The conversation was part of Jubilee’s Surrounded series on YouTube and was originally titled “A Christian vs 20 Atheists” (later changed to “Jordan Peterson vs 20 Atheists”). One would think that with a title like that, God might come up.

Still, Peterson’s stammering might not be the worst answer he could give—especially in a cultural moment such as this.

Peterson is, of course, a polarizing figure, which is probably why he was invited to the debate. His fans are devotees who love to love him, and his detractors love to hate him.

Added to this, though, is Peterson’s unique caginess on these kinds of questions. Known as an atheist/agnostic throughout his career, Peterson has taken to wearing a suit featuring iconography of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus and has taught courses on the text of books of the Bible.

But he doesn’t seem keen to talk about whether any of this actually happened in space and time.

For instance, in a different conversation with New Atheist Richard Dawkins on whether Cain and Abel—a story Peterson claimed is central to understanding human history—actually existed, Peterson quibbles about what it means to be “true.”

To some degree, Peterson’s reticence at that point is somewhat warranted. Dawkins, after all, has a literalist and materialist sense of scientific objectivity that Peterson no doubt wanted to pierce with the—forgive me—truth that there are realities outside the purview of naturalistic investigation.

The difference between the two mindsets was on display when he and Dawkins disagreed over whether dragons exist. Dawkins, of course, is thinking in terms of phyla and species, while Peterson is thinking in terms of Jungian archetypes of the “hero’s journey.”

Even so, Peterson’s evasiveness about what is true is usually recognized as just that: evasion.

An old cliché in Christian circles is that when a pastor search committee asks a candidate, “Do you believe in the resurrection of Jesus?” and the response is, “What do you mean by resurrection?” that means the candidate doesn’t believe in the resurrection.

The fact that Peterson turned the question around on his interlocutors is not in itself a miscarriage of argument. Jesus sometimes answered questions head-on, sometimes challenged the assumptions of the question, and sometimes refused to answer at all.

When the chief priests, scribes, and elders asked Jesus by what authority he did the things he did, Jesus refused to answer until they answered a question of his own: “Was the baptism of John from heaven or from man?” (Mark 11:30, ESV throughout).

Either answer would have put the temple leaders in a political bind—of the sort they were trying to create for Jesus, not for themselves—so they replied, “We do not know.” Jesus responded, “Neither will I tell you by what authority I do these things” (v. 33). Jesus wasn’t refusing to argue; he was winning the argument with his refusal.

The apostle Paul likewise famously interrogated his Athenian questioners about their altar to an unknown god and about their own poems. In doing so, he showed them that their assumptions were inconsistent on their own terms (Acts 17:16–34).

If one is going to engage in these kinds of debates, it is true that one should first deconstruct the misconception behind them—that God is an object or an idea to be investigated like some other “thing” or concept rather than, as Paul put it, the one in whom we “live and move and have our being” (v. 28).

The examples of Jesus and Paul, though, do not seem to fit the context of Peterson’s caginess here.

Jesus was facing questions not because of his ambiguity but because of his clarity. He had just driven the marketers out of the temple, seeming to equate the dwelling place of God’s presence with his own house. Paul was summoned to Mars Hill for his debate because he was “preaching Jesus and the resurrection” (v. 18).

For a believer, saying “I don’t know” to a question about who the Nephilim of Genesis 6 were or how predestination fits with human freedom are perfectly legitimate. But to refuse to say whether God lives or not is another matter.

Looking at Peterson’s answer through a grid of suspicion, we would probably conclude that he is more like Jesus’ religious questioners referenced above than like Jesus himself. Peterson saw that either answer would lose part of his constituency, so he punted. From that perspective, we might assume that he was less like Jesus remaining silent before Pontius Pilate and more like Pilate—right down to the irritated retort “What is truth?” (John 18:38).

Through a less cynical lens, however, we might wonder if Peterson wouldn’t answer the question because he couldn’t.

A more charitable view might wonder if, like Nicodemus, Peterson was asking questions without yet knowing the answers (John 3:4). Or perhaps, like C. S. Lewis at the first stages of his grappling with God, Peterson is becoming broadly convinced that something or someone is out there beyond his sight, but he’s not yet sure what or who that is.

Whatever the case, I stand by my assertion that Peterson’s non-answer is better than some possible answers. One of those would be to say, “Yes, I’m a Christian” and “Yes, I believe in God,” meaning “I believe that belief in God is good for society” or “I believe in Christianity as the moral and cultural heritage of Western civilization.”

Much of what goes under the name of Christianity right now—a claim to Christian identity without personal faith in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob through the mediation of the crucified and risen Christ—is, in fact, worse than unbelief.

Jesus once healed a man who was born blind, and the religious leaders were outraged that he did this on the Sabbath. When asked about it, the formerly blind man’s parents were afraid they would lose their place in the community and said, “We know that this is our son and that he was born blind. But how he now sees we do not know, nor do we know who opened his eyes” (John 9:20). Jesus had no harsh words for them.

The man himself said of Jesus, “Whether he is a sinner I do not know. One thing I do know, that though I was blind, now I see” (v. 25). Jesus does not condemn this either.

But of the religious leaders themselves, Jesus said, “If you were blind, you would have no guilt; but now that you say, ‘We see,’ your guilt remains” (v. 41).

To be a “Christian” because one is Western or because atheism has proven bad for nations and cultures is ancestor worship—not the gospel. To claim God because God is useful is to construct an idol. The living God despises all idols, but especially those that claim to be him (Ex. 32:8; 1 Kings 12:28; 13:1–3).

In that sense, the synthesis that Peterson now attempts of mining the Bible for Jungian archetypes is not a step on the way to Christianity but a step away from it, just as every other attempt at syncretism is.

As the orthodox Presbyterian J. Gresham Machen wrote, the kind of useful “Christianity” that cleans up societies, shores up cultures, or provides useful life principles for people is an entirely different religion than that of Christ and him crucified.

Peterson lost that YouTube debate—something he’s not used to. He lost it because the atheists on that stage were, on one point, more biblical than he: If Christ is not raised, faith is futile and we are still in our sins (1 Cor. 15:17).

They knew that if this is true, not just metaphorically but actually true, then after all the “what is truth” questions are over, “if in Christ we have hope in this life only, we are of all people most to be pitied” (v. 19).

But maybe behind Peterson’s hesitation, there’s something more than artful dodging. Maybe he’s listening for what “come follow me” might actually mean.

Peterson’s name is literally “Peter’s son.” And maybe he is. Perhaps he is following in the way of Simon Peter, still answering the question “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” but not yet ready to answer for himself (Matt. 16:13).

The question “Who does YouTube say that I am?” is relatively meaningless. The question “Who do you say that I am?” is life or death.

“I don’t know” is not a final answer to the most important question posed on YouTube or in life. But sometimes it’s a good start.

Russell Moore is the editor in chief at Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.