In the sweltering summer of 1925, crowds flocked to the small town of Dayton, Tennessee. Hundreds of journalists documented a weeklong courtroom melodrama. The trial centered on a high school teacher, John T. Scopes, who was charged with violating the Butler Act, a law passed earlier that year prohibiting public schools from teaching human evolution.

This year marks the centennial anniversary of the Scopes “Monkey” Trial, which was culturally significant in American history as it cemented the rift between modernists and fundamentalists in both church and society. Much like today, Christians back then were working through an identity crisis closely tied to political shifts and deep theological disagreements.

In the years since the Scopes Trial, anti-evolutionism became tightly linked, or “bundled,” with orthodox Christianity in the American church. That is, until the evangelical movement began disentangling questions of science from the essential gospel truths to allow for more thoughtful and faithful engagement with both.

Although political verdicts on hot-button issues matter, the Scopes Trial reminds us that the way theological crises are handled can shape generations as much as their outcomes can.

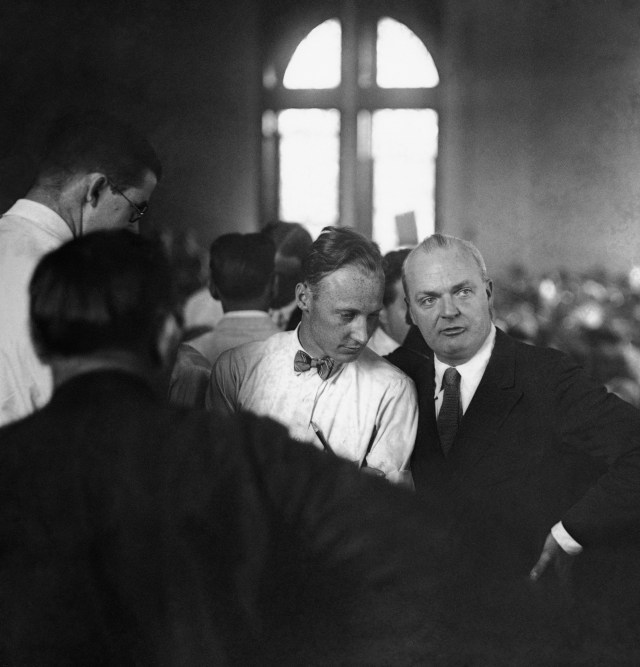

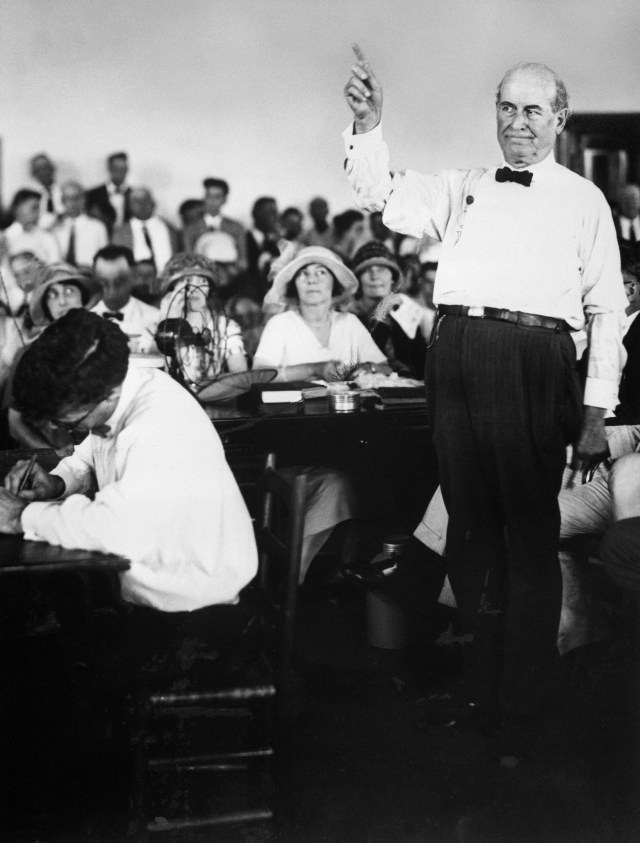

On the surface, the Scopes Trial was about human origins, evolution, and the Bible. Its mythic allure emerged from the dramatic public showdown between two titanic figures—William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow.

Bryan, the star prosecutor, was a charismatic and eloquent politician. Thrice a presidential candidate, Bryan opposed human evolution and advocated for the Butler Act. Darrow, a famed defense attorney and militantly anti-Christian agnostic, teamed up with the nascent American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to defend Mr. Scopes.

The Butler Act specifically prohibited “[teaching] any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

The ACLU’s initial strategy was to argue that Scopes was not violating the law because evolution was, in fact, compatible with Genesis—an interesting defense given Darrow’s intensely anti-Christian stance. The judge, however, dismissed this out of hand.

Bryan could also cross-examine the ACLU’s experts, all of whom were theological modernists who denied Jesus’ bodily resurrection—an opening Bryan would have seized to discredit them as unorthodox. So instead, the exasperated defense pivoted to ask for a swift guilty verdict that they could appeal. The trial seemed to be ending as quickly as it had started.

But on the last day of the trial, Darrow made a stunning move. He called Bryan himself to the stand as a witness. Prosecutors never testify at their own trials. Yet Bryan agreed.

The day was so hot that proceedings were moved to a stage outside the courtroom. To the cheers of a growing crowd, the two legal champions sparred in a debate that had little to do with Scopes himself. Darrow’s incisive inquiry was wide-ranging, including a memorable question about where Cain got his wife. He aimed to expose Bryan—and his fundamentalist literalism—as inconsistent, ignorant, and bigoted. Bryan, undeterred, seized the opportunity to proudly confess his belief in literalism and Christianity.

The crowds were captivated by the grandstanding, but the judge was not amused. Abruptly, he ended the trial with a guilty verdict. Bryan and Darrow continued their feud in print, but just a week later, Bryan died in his sleep, cementing the trial’s legendary legacy and significance.

To some, the Scopes Trial and Bryan’s untimely death seemed like the last gasp of religious fundamentalism. But to others, Bryan died a hero, defending true Christianity in an ever-evolving culture war, the shadow of which we live in today.

Although the Scopes Trial was entertaining, the larger fundamentalist-modernist controversy was not a friendly debate. It began among Presbyterians and spread to nearly every American denomination, most of which eventually split as a result. It became part of a larger rift in society at the time—when, to echo Willa Cather, “the world broke in two in 1922 or thereabouts.”

The tensions, and even the cultural panic, that we see today between progressive and conservative Christians are much like the rancor that steadily developed between modernists and fundamentalist Christians beginning in the late 1800s.

As the modernist school of theology made its way from Europe to leading seminaries in the US at the time, the controversy first began playing out in academic journals, with back-and-forth exchanges between theologians like B. B. Warfield and Charles Augustus Briggs.

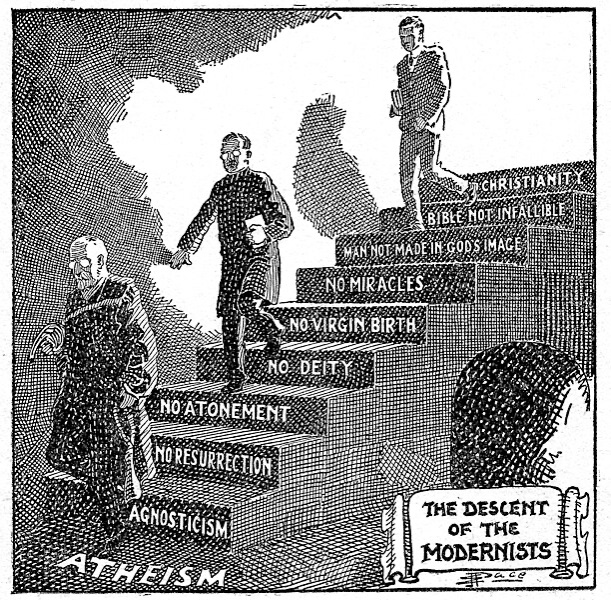

The modernists called themselves Christians, but they rejected the bodily resurrection of Jesus, the Virgin Birth, and all other miracles. They saw the Bible as authoritative but also riddled with errors. According to Briggs, Warfield’s notion of biblical inerrancy was “a ghost of modern evangelicalism to frighten children.” The Christian faith, in their view, needed to modernize and forsake these backward beliefs.

This debate soon spilled into church polity. In 1909, three seminarians sought ordination in the Presbyterian Church though they were unwilling to affirm the Virgin Birth. After intense debate, the three were eventually ordained, shocking many.

This controversy led to the formation of the fundamentalist movement, dedicated to preserving historical Christianity. Against the doctrinal drift of modernists, the group emphasized five “fundamental” doctrines: (1) the inerrancy of Scripture, (2) the Virgin Birth, (3) the atonement for sin by the death of Jesus, (4) the bodily resurrection of Jesus, and (5) the historical reality of Jesus’ miracles.

At first, fundamentalism was not bound so tightly to the rejection of evolution. Biola University published about 90 essays from 1910 to 1915 known as The Fundamentals, which defined the movement’s identity. These essays were full of evangelical diversity. There were a few anti-evolution arguments, but many also expressed cautious openness to the theory, were the science to pan out.

But when Bryan came on the scene in the early 1920s, fresh from advocating for women’s suffrage and temperance, he entered the origins debate in full force. He became convinced that the pernicious idea of evolution was the root cause of the modernist slide away from historical Christian faith.

This makes sense, since in Bryan’s context, every Christian that affirmed human evolution at the time was a modernist who had departed substantially from many important doctrinal claims of historical Christianity. In many cases, modernists appealed to evolutionary science to justify the controversial theological positions they preferred, including a way to understand creation without the miracles they had eschewed.

Bryan had no theological objections, in principle, to an ancient earth or evolution among animals and plants. But human evolution was altogether different in his mind. The idea that humans shared ancestry with monkeys and apes was, according to his interpretation of Scripture, in direct conflict with Genesis.

In many ways, Bryan’s advocacy, so widely disseminated at the Scopes Trial, caused rejection of evolution to become bundled together with fundamentalism, much as evolution was bundled together with modernism. So in some sense, the bundling of anti-evolutionism with orthodox Christianity is almost a historical accident. If not for Bryan and the Scopes Trial, it might not have happened quite this way.

While Bryan did not realize it at the time, there are ways to affirm human evolution that align with orthodox theology. In fact, a growing number of evangelicals today have shown that evolution is entirely compatible with even a very literalistic reading of Genesis—including a historical Adam and Eve from whom we all descend, in a literal garden, created directly by God without parents of their own.

The Scopes Trial was a key battle in the historic war between fundamentalists and modernists—but its legacy offers us much to learn from a century later.

One lesson might be that we can often overreact to new ideas, particularly in times of great cultural change. In our response, we can bind reactionary politics and ideologies to our Christian practice. This path, it seems, is all the more likely in times when we are struggling to define our theological identity, as is certainly the case right now for evangelicals.

A similar pattern played out with social action and the gospel. As modernists abandoned belief in the resurrection of Jesus, they increasingly emphasized the importance of compassionate justice instead—embracing what became known as the “social” gospel. Fundamentalists rightly rejected this theological error. But they also overreacted, growing suspicious of the Christian duty to do good and seek justice in society.

It wasn’t until the rise of global evangelicalism in the 1960s and ’70s that Christians began unpacking some of the bundles created by the modernist-fundamentalist divide. Leaders like John Stott, Billy Graham, Carl Henry, and Francis Schaeffer emphasized the gospel of Jesus dying and rising for our sins, but they also reclaimed a strong emphasis on social action as a necessary outworking of the gospel.

Another lesson is that political and legal victories can be pyrrhic and even disastrous in the long run. In Tennessee, Bryan and the anti-evolutionists won politically. They passed the Butler Act. They won the Scopes Trial in Dayton. They celebrated their champion too; Bryan died a hero.

But the fallout from these proceedings were far worse than they anticipated. For many important onlookers, like renowned journalist H. L. Mencken, Darrow had entirely exposed Bryan—and his fundamentalism—as backwards, ignorant, and bigoted. This image stuck and became entrenched for decades.

Getty

Getty Getty

GettyThe Scopes victory, moreover, did nothing to prevent modernists from taking over most denominations and seminaries in the country. Even Princeton Theological Seminary, where Warfield and others had argued effectively against modernism, became solidly modernist by the 1930s.

Theologians who aligned with orthodox, historical Christianity either retreated or were expelled from most institutions. And as they withdrew, they formed their own publishing houses, universities, and seminaries.

The fundamentalists eventually became so sequestered from broader society that many thought they had died off. This isolation only further cemented the prevailing narrative of Darrow’s portrayal of Bryan and fundamentalism—especially as the story of Scopes was told and retold through popular movies and plays like Inherit the Wind.

On paper, the Scopes Trial was a victory for Bible-believing Christians. But it also marked the beginning of Christian cultural isolationism—which eventually cost us our voice of influence in contributing to moral and ethical discourse in the public square.

Decades later, evangelicalism encouraged Christians to emerge from the shadows, offering them a better way to engage with secular society. As Stott wrote then, “A Christian mind should respond to contemporary culture neither with a blanket rejection nor with an equally indiscriminate acquiescence, but with discernment.”

In some ways, the spirit of the modernist-fundamentalist debate is still with us today. It is present, for instance, in the political tensions between believers on issues like critical race theory; diversity, equity, and inclusion; sexuality and gender; abortion; and immigration.

And while some Christians are celebrating various legal and political wins for biblical principles in the public square, these victories may be costing us our compelling witness and the chance for lasting cultural change.

American society is oriented toward public advocacy. Yet the political and court systems are rarely, if ever, the best way to think through nuanced realities and complicated concepts. Political and legal activism may be important at times, but we need other ways to understand and work through our differences as citizens—and especially as Christians.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsThe roots of our divides are often fundamentally theological, and our disagreements matter—we need to work through them in light of Scripture. But good thinking takes time. Moving too quickly can ossify reactionary errors, with real consequences that ripple for generations. For this reason, how we respond to the current cultural moment matters. Our actions today will shape the sort of church we leave behind for our children.

Perhaps the final lesson of Scopes is more hopeful: Just as bad “bundles” can be wrapped together in times of turmoil, they can also be disentangled.

We are in a time of great societal change, as many old coalitions and approaches are being dissembled and reconstituted in surprising ways. Both in the US and globally, it is not clear what the future holds for Christian faith and practice. And although we see some indications, we do not yet know what the new ideological bundles will be.

This provides the church with the unique opportunity to witness to the gospel apart from political outcomes. Right now, our values and identity are being reexamined and renegotiated, causing real anxiety and discomfort. But instead of overreacting and making new mistakes to correct old ones, we can resist the drumbeat of outrage and panic and steady the pendulum swing.

Once upon a time, the evangelical movement charted a path for the church to wisely navigate the divides of its day. Can we do the same?

S. Joshua Swamidass is a physician-scientist, associate professor of laboratory and genomic medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, founder of Peaceful Science, and author of The Genealogical Adam and Eve.