Francis Samaan’s body is in Jordan, but his heart is in Sudan.

The third-year theology student sits in a quiet commons area adjacent to the darkened chapel of Jordan Evangelical Theological Seminary (JETS) in Amman, the country’s capital. Though he currently lives and works at the seminary’s imposing limestone campus—filling in for an Egyptian employee who’s traveling—Samaan’s mind is split between his studies and his home country, where civil war has raged since April 2023.

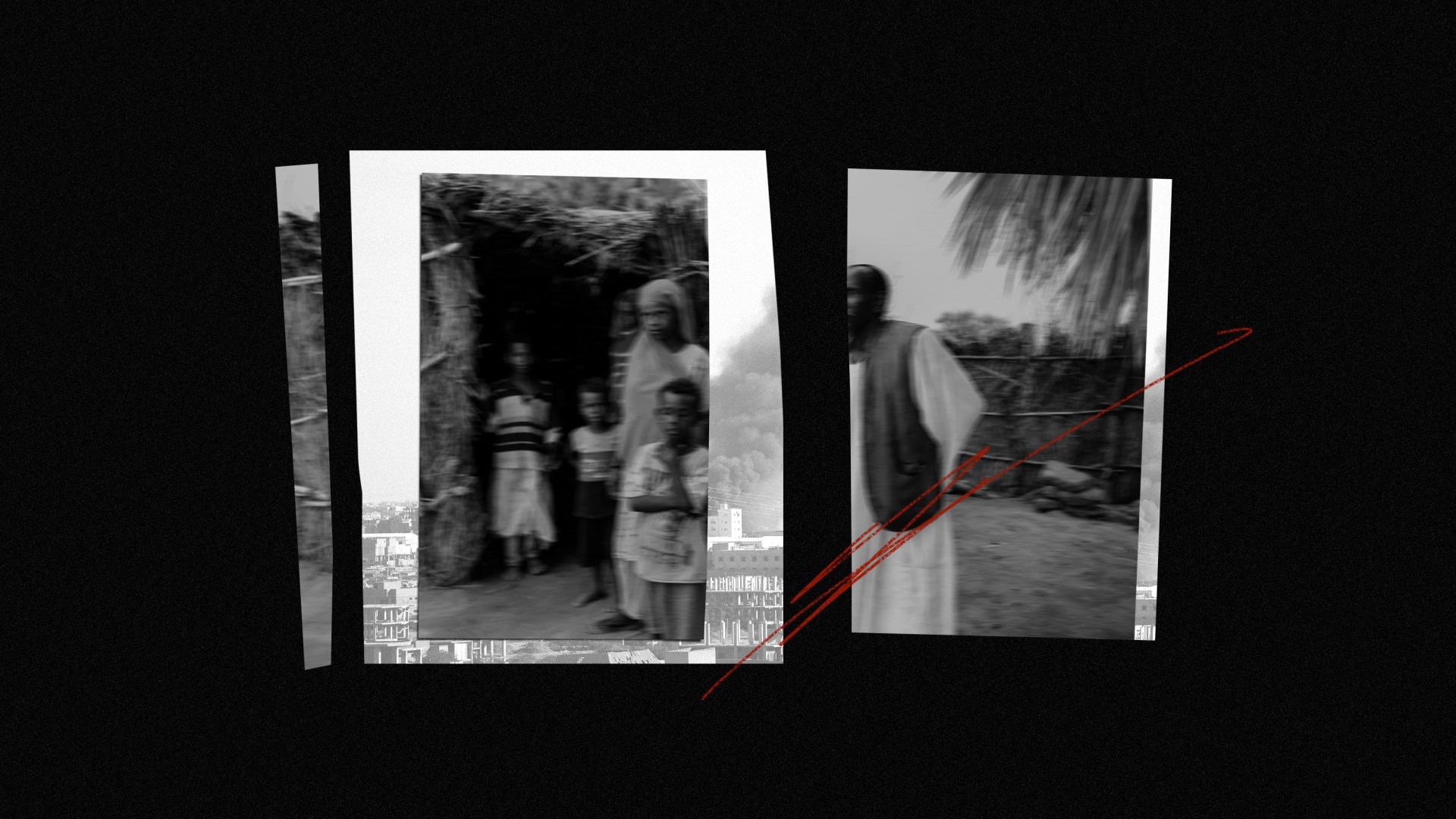

Samaan’s wife, Hanaa Kalo, and his six-year-old twins are safe in Egypt—they reached Cairo shortly after war broke out, enduring a harrowing seven-day bus ride from Khartoum, Sudan. But his mother, his siblings, and their children remain in Sudan’s ravaged capital. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the paramilitary group battling the government-led Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) for sovereignty in the African nation, looted their home, stealing even their mattresses and cell phones.

When Samaan’s relatives contact him, they have to walk to borrow a phone. Like many in Sudan, they currently eat just one meal a day, usually rice and lentils.

“Each one is waiting for when he’ll die,” Samaan said of Sudan’s Christians, a persecuted minority of around 5 percent in the country of 50 million. “This is the reality right now. No one has hope that things will change tomorrow.”

On the Sudanese conflict’s second anniversary, UN Secretary-General António Guterres summarized its catastrophic results: 12 million displaced, with 3.8 million spilling into neighboring countries like Ethiopia, Chad, and Egypt. Famine has been declared in at least five areas, with 25 million people facing acute hunger. Death toll estimates reach at least 150,000.

Though the wars in Gaza and Ukraine garner more press attention, aid groups consider Sudan as having the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. Many Sudanese people are subsistence farmers. But violence and displacement have drastically impacted agriculture, throwing half the country into food insecurity. In 2023, Sudan’s Annual Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission reported a 46 percent decline in the production of local grains like sorghum and millet compared to 2022, linking this decrease to the conflict.

Recent funding cuts made by the Trump administration have only exacerbated the crisis. In 2024, the US was Sudan’s largest humanitarian donor, providing funding for close to half the aid needed in the country. Since the USAID freeze in late January, ACAPS, an independent data analysis group focusing on the humanitarian sector, reported that the cuts affected a broad swath of aid groups.

UN organizations, international and national nonprofits, and grassroots-level community responders have been forced to fire staffers, reduce hours, and cut programs, ACAPS said. In Khartoum alone, 80 to 90 percent of emergency food kitchens were shuttered.

The civil war has particularly hurt Christians. This year, Open Doors ranked Sudan as the fifth most difficult place in the world to be a Christian. The organization’s annual World Watch List stated that “violent extremist groups have exploited the deteriorating security environment to systematically target Christians.”

Boutros came to Amman from Khartoum in 2018 to pursue a master’s degree in biblical studies at JETS. He also remains in contact with his relatives in Sudan—and with his fiancée, Sara, whom he’s not seen in seven years. (Christianity Today agreed to use pseudonyms for the couple since Boutros currently does not have legal status in Jordan.) The couple, who met more than a decade ago, got engaged in 2020 after his family representatives met with hers to ask for her hand.

Sara worked at a pharmaceutical company in Khartoum before war forced her family to flee to a village in eastern Sudan’s Kassala State. Sometimes she sits outside her family’s mud-brick house to catch an internet signal to talk with Boutros. She spoke with CT from this spot, with cars and motorbikes passing on the dirt road in front of her, shrieking children playing around her, and a dove cooing near her head.

Farms surround Sara’s family’s village, but some days they eat just one meal and other days none. She said their situation gets worse every day. Still, Sara finds encouragement in the story of Job, who lost all his possessions, his children, and his health but not his faith.

“We’re human, so … we have moments when we’re weak,” Sara said. “But we come back and say, ‘The Lord will strengthen us and make us steadfast in our faith,’ in spite of all the challenges and difficulties we are going through.”

In early May, a series of drone strikes—presumably guided by the RSF—hit Port Sudan, a coastal city one state north of Sara’s home in Kassala. Port Sudan has served as the country’s wartime capital and a hub for international aid. Until now, it has been untouched by fighting, a relatively calm refuge for hundreds of thousands of displaced civilians.

After the strikes, billowing clouds of noxious smoke rose from the targeted fuel depot. The drones also hit a power converter and hotel, as well as Sudan’s only operating international airport.

Sara has dreamed about flying from Port Sudan’s airport to Juba, South Sudan. There she could obtain a South Sudanese passport, enabling her to travel and reunite with Boutros. But the drone strikes on the airport highlighted the fragility of her plans. Even if she had the money for a plane ticket to Juba—approximately $600—would the airport be open when she was ready to leave? Once in Juba, where would she find funds for a passport and travel?

Though Boutros and Sara face enormous hurdles to reunification, Boutros continues to put his trust in God—for his future marriage and for the outcome of Sudan’s never-ending conflict. Boutros was born in the middle of war in South Kordofan’s Nuba Mountains. He has not seen his mother since 2010. Early in the current war, he and fellow Christians in Amman gathered in a cold, damp room to grieve the death of his brother to random shelling.

“Satan sees in a limited way, but God sees everything,” Boutros said. “Satan makes war and kills, but at the same time, God allows a person to see and ask, ‘Who is this person who’s killing?’ He starts to draw close to Christ, to see a different life. He can forgive others.”

And there is much to forgive. In April 2024, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom reported that more than 150 churches had been damaged after a year of war. Since then, the SAF bombed Al-Ezba Baptist Church in Khartoum North on December 20, killing at least 11. The RSF attacked a church in Gezira State during prayer on December 30, leaving 14 injured. In October, the SAF arrested 26 Christian men fleeing with their families, accusing them of partnering with the RSF.

In 2013, while Samaan was working as an accountant for the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Sudan, security forces arrested and jailed him alone in a windowless room for three months. Every morning, they beat and interrogated him. They told Samaan he could work for them as a spy, supplying information about local churches. If he refused, they promised they wouldn’t let him rest.

Samaan refused. After his release from prison, he was forced to report to the police station every morning and sit idly until evening. This continued for six months, in which time he lost his job. After Samaan married Kalo in 2015, the police continued to hound him, monitoring their home and sending threatening text messages.

Finally, in 2018, Samaan’s name appeared in the newspaper, which said he was wanted by the government for “preaching the gospel of Christ.” His friends smuggled him to the airport, and he fled to Jordan. Kalo, six months pregnant with twins, woke to find her husband gone.

“Sometimes I ask, ‘Where are you, Lord?’” Samaan said. “All these things—six, seven years, I haven’t seen the kids, and my wife is tired, and they ask, ‘Where are you, Daddy?’ Until now, we don’t know when we’ll be able to meet each other.”

With his work-study job at the seminary, Samaan makes a small stipend. Every month he sends a portion of it to Cairo to help his wife pay for rent and food. His children should be in first grade, but they haven’t been able to pay tuition fees. Samaan believes God called him to study, but sometimes he wonders if he should quit and get a full-time job so he can provide for his family.

His mental state mirrors that of many Sudanese Christians—both inside and outside Sudan. “You know how sometimes you get to the point that you’ve lost hope, you don’t know how to pray?” Samaan said. “Inside you are oppressed, broken, sad—you need someone to help you. This is what we need now—people to help us in prayer, spiritually, emotionally, economically. People to encourage us.”