I remember the day my hope failed.

The seminary where I taught in South Africa had run out of money. Facing impending closure, faculty and students packed into a classroom to pray. These people had saved and sacrificed for years to arrive here from across the continent. Some had survived war, famine, drought, or dictatorship. As I listened to their voices crying to the Lord, suddenly I ran out of words. I realized, These people have a way of hoping that I have never learned.

Since then, I’ve come to think about hope in terms of quality more than quantity. That’s not because the numbers look great here in the American church: According to a recent Pew Research Center study, less than half of religiously affiliated US adults (47 percent) felt hopeful in their past week. That’s 12 percentage points higher than atheists, but it’s still a lot of hopelessness.

Yet a more troubling picture emerges if you look at the type of hope we do have. One anthropologist, Omri Elisha, who studied suburban Christians in Tennessee, concluded that Christians tend to talk about hope as a “motivational linchpin” for evangelical outreach and service. When the Christians he studied tried to put that hope into action, then, they became mired in “compassion fatigue.” They were immersed in admonitions to have more hope, but their way of hoping wasn’t working.

What we need is not just more hope but the right kind of hope.

Hope is a way of orienting oneself toward an unknown future that anticipates good. But that definition leaves room for a lot of variety. Hope is a multidimensional thing; it cannot be quantified on a simple scale from less to more. When it comes to the nitty-gritty of hoping in hard times, we need to pay attention to which narratives of hope we’re following.

As an anthropologist, I study those narratives, which we absorb from our surrounding cultural settings to make sense of the world. We take in stories and assumptions about how to avoid the bad, attain the good, and get from the one to the other. In other words, we’re immersed in cultural narratives telling us how to hope.

Sometimes we hope because we trust in progress, powerful leaders, or our own prowess. Sometimes we hope for the comfort of cozy houses and lucrative jobs. If we’re honest, many of our ways of hoping have little to do with the hope that has propelled the church to follow Jesus through the ages (Rom. 8:24–25). We need less of the shallow maxims embroidered on decorative pillows and shouted in political rallies. How instead do we find a thick, stubborn, real hope that can sing the blues and walk a tightrope?

Take, for example, the hope that King Ahab exemplified in 1 Kings 22. Ahab was a terrible king by any standard. In one of his many misdeeds, he decided to conquer neighboring Ramoth Gilead and found 400 prophets to tell him exactly what he wanted to hear: Have hope, because everything is going to be fine.

But one prophet, a man named Micaiah, was bold enough to tell Ahab that his hopes were delusional. Ahab pouted about Micaiah like a grumpy toddler. “There is still one man through whom we can inquire of the Lord,” Ahab said, “but I hate him because he never says anything good about me, but always bad” (v. 8). When Micaiah broke the news that Ahab’s imperial ambitions would fail, Ahab threatened to put Micaiah in prison then went to war anyway. Because he was scared, Ahab disguised himself as an ordinary citizen. Nevertheless, a stray arrow struck him through a crack in his armor, and he died a disgraceful death.

You have probably seen people clinging to Ahab’s kind of delusional hope. He cared only for outcomes that would be favorable for himself, surrounding himself with counselors willing to whitewash realities he didn’t like. He expected troubles to resolve easily: just a little battle, like a half-hour sitcom. He clung to power and longed for a mythical past when he had even more power. He was terrified of real danger but also terrified of having his sin exposed. He hoped for a future of more control, more power, more of himself.

Delusional hope is not always so selfishly aggressive. It can also produce dangerous passivity, as Martin Luther King Jr. warned half a century ago. When Birmingham officials imprisoned King for leading civil rights demonstrations, white clergy wrote an open letter counseling King to delusional passivity: “We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized, but we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.”

In his now-famous response, King taught a different way of hoping. “Maybe I was too optimistic,” he reflected. “Maybe I expected too much. I guess I should have realized that few members of a race that has oppressed another race can understand or appreciate the deep groans and passionate yearnings of those that have been oppressed, and still fewer have the vision to see that injustice must be rooted out by strong, persistent and determined action.”

King rejected naive optimism. In its place, he taught a weather-beaten Christian hope: “We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and persistent work of people willing to be co-workers with God.”

King wasn’t merely disappointed that people failed to advocate for justice. He was disappointed in their dangerous kind of hope, the notion that justice would simply appear out nowhere, following neither action nor repentance. Delusional hope of this kind is an alluring lie. It tells us we need not bother becoming coworkers with God.

Biblical hope is never delusional. It is not naively optimistic or afraid of suffering. In fact, it grows perseverance out of suffering (Rom. 5:3–5). It rests on the foundation of Jesus Christ, who interrupts our broken world with grace (1 Pet. 1:13) and is characterized by selfless action and discipline (1 Pet. 1:13). As theologian Miroslav Volf put it, abiding Christian hope “is not based on accurate extrapolation about future from the character of the present.” Unlike shallow optimism, it never depends upon good omens but trusts in God and his goodness even, Volf says, “against reasonable expectation.”

For the past four years, I’ve been interviewing Christians about the ways they hope in relation to racism. I’ve noticed that Christians who are committed to pursuing kingdom justice for the long haul have generally scoured away optimistic, power-loving, Ahab-style ways of hoping. They live in a deeper and more biblical hope that rests on grace, grows out of suffering, aims for shalom, and calls for action.

You can assess the shape of your own hope using prompts I’ve used in interviews. Try filling in the blanks in this sentence: “I used to hope ____, but now I hope _____.” Try filling in what you hope for, and then also answer a second time with adverbs. Perhaps you have hoped eagerly, naïvely, or blindly. Then ask yourself these questions: Why do you hope? What is the goal of your hope? And how does your hope shape your life? What concrete difference does it make?

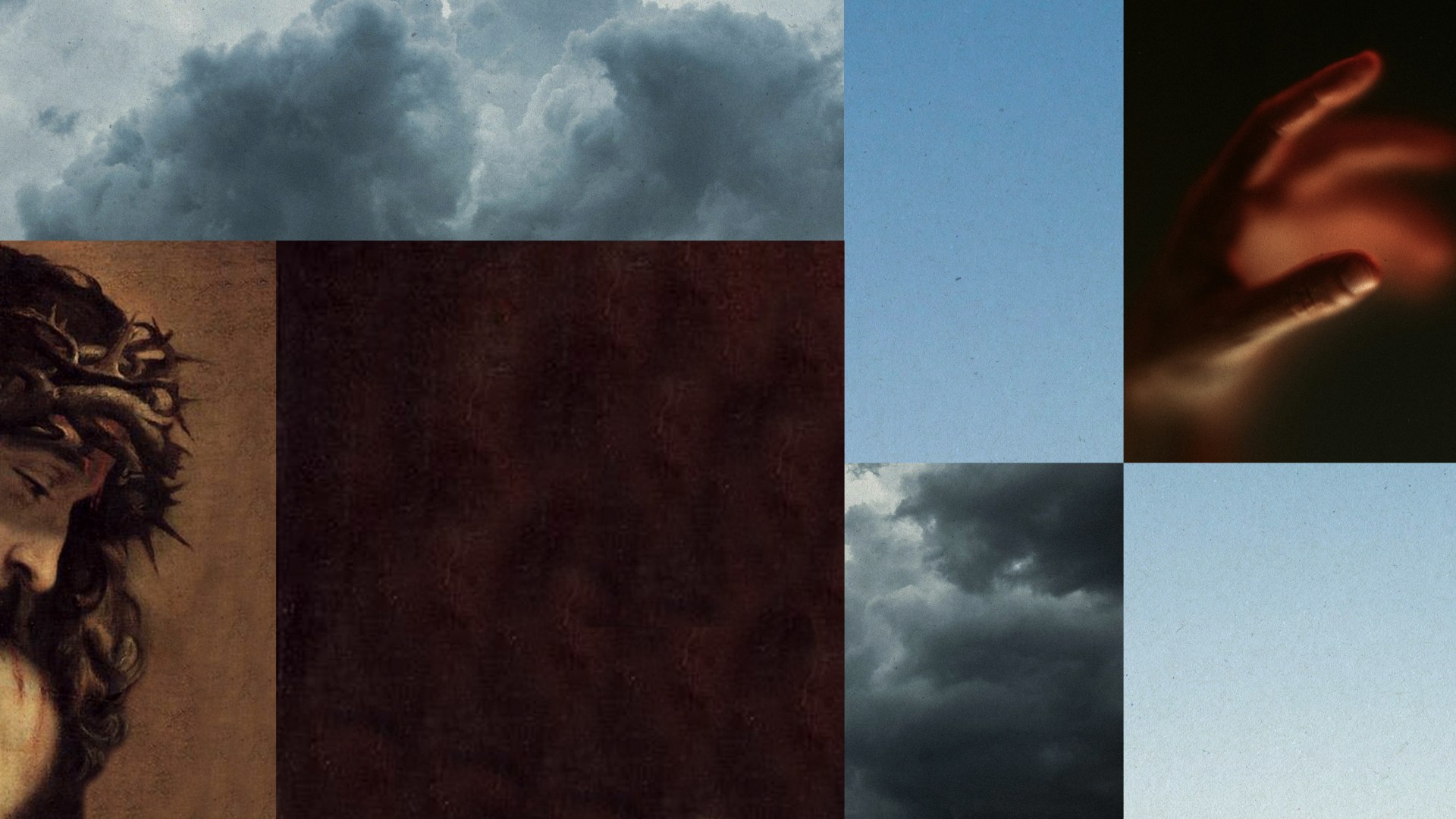

When I asked these questions of Christians who had worked for decades to bring about justice in difficult circumstances, they told me of a profound hope that combined both lament and joy. “I find no hope in [denying] what really is happening,” one woman told me. “My hope is not shiny or happy at all. It’s totally bruised and bloodied, and it’s scraping by my fingernails. On [some] days you may not be able to see it. But there’s maybe a scrap of it hanging on and pressing on.”

These days, when I encounter disappointments, I’m not just trying to scrounge up scraps of a tired old hope. I’m looking to my brothers and sisters in Christ across the globe and across the centuries, learning how to dig my fingernails into a rugged hope founded firmly on Christ, who died and rose again.

Christine Jeske is associate professor of anthropology at Wheaton College and the author of four books, including the forthcoming Racial Justice for the Long Haul: How White Christian Advocates Persevere (and Why). She previously worked for a decade in Nicaragua, China, and South Africa.