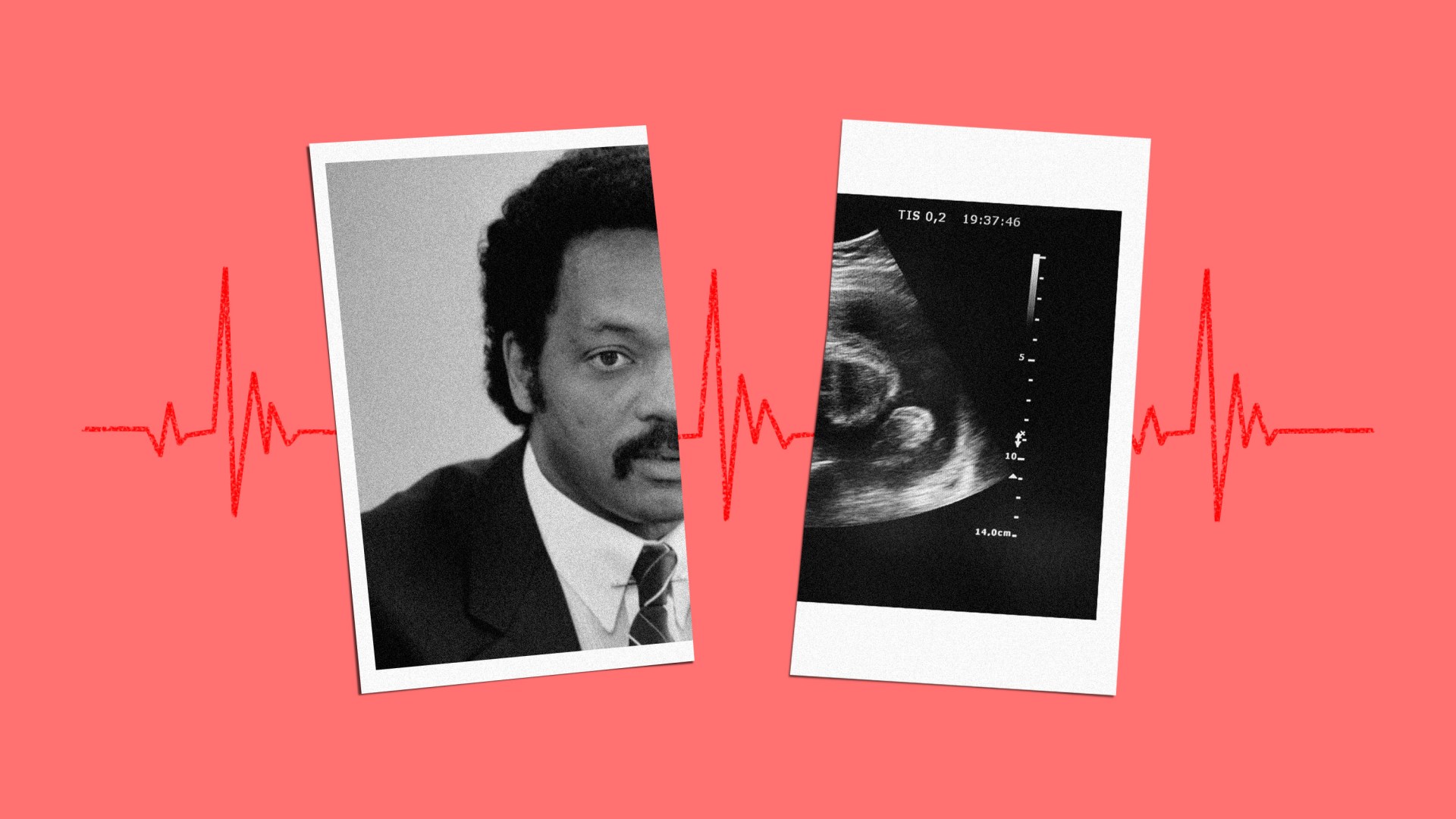

In 1977, the civil rights activist Jesse Jackson published an article in the National Right to Life News that denounced the injustice of abortion. Human life, Jackson said, begins at conception, and it must be valued from its earliest existence. “What happens to the mind of a person, and the moral fabric of a nation, that accepts the aborting of the life of a baby without a pang of conscience?” Jackson asked. “What kind of a person, and what kind of a society will we have 20 years hence if life can be taken so casually?”

But just six years later, when Jackson was running for the Democratic presidential nomination, he took a different stance. Not only did he advocate keeping abortion legal; he also supported Medicaid funding for the procedure.

Contemporaries were taken aback by the abrupt shift. “In the past, he has been quoted as equating abortion with murder,” The New York Times noted in 1983.

Cynics might argue that Jackson’s shift on abortion was an act of political opportunism—an attempt to win the nomination even at the cost of his convictions. But they would probably be wrong, for Jackson’s shift was part of a much larger pattern among African Americans: In the 1970s, Black Protestants were more likely than any other group of American Christians to oppose abortion. Today they are more likely than any other group of American Christians to support abortion rights.

That change on public policy, however, did not neatly correspond to a change in ethical convictions. Many African American Christians continue to believe abortion is a grave evil, and it’s possible to imagine an alternate timeline in which different political framing of pro-life arguments from white Christians could have built lasting bridges with pro-lifers in the Black church. Unfortunately, by failing to understand the reasons for this massive shift among African Americans, the predominantly white pro-life movement lost erstwhile allies and opportunities to press our moral case in the public square.

That divergence began in the early 1970s, when most advocates of abortion rights chose one of three frameworks for their arguments: women’s equality, personal liberty, or population control.

Politically progressive African Americans like Jackson had no objection to women’s equality, and they were sympathetic to many personal-liberty arguments too. But the presence of a sizeable number of population-control advocates within the abortion rights movement alarmed them. “Politicians argue for abortion largely because they do not want to spend the necessary money to feed, clothe and educate more people,” Jackson wrote in 1977.

He was not alone in that view. Nearly every Black American who spoke against abortion in the 1970s called it “genocide”—which was the term that Jackson’s own denomination, the Progressive National Baptist Convention, used in its anti-abortion resolution in 1973.

It was also the term that civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer employed. “The methods used to take human lives, such as abortion, the pill, the ring, et cetera, amounts to genocide,” she declared in a speech at Tougaloo College in Mississippi in 1971. “I believe that legal abortion is legal murder.”

A former sharecropper who had lived in poverty her entire life and had been arrested and brutally beaten for attempting to register to vote, Hamer had firsthand knowledge of the type of “genocide” she described. Earlier in life, she had received a forced hysterectomy, an all-too-common experience for African American women of her generation and socioeconomic class.

Jackson thought the pro-life movement should focus its efforts on assistance to the poor, in contrast with the abortion rights movement, which he seemed to think at the time drew on the support of middle-class white people who did not have much regard for poor Black people and who did not want to invest in helping the poor. That focus would be an antidote to the “politicians [who] are willing to pay welfare mothers between $300 to $1000 to have an abortion,” he said, “but will not pay $30 for a hot school lunch program to the already born children of these same mothers.” Jackson himself had grown up in poverty as the child of a single mother, and he thought the campaign against abortion could not be decoupled from advocacy for the rights of families in circumstances like those of his own childhood.

White pro-lifers often endorsed these aims. But there was one key area where they differed: The belief that abortion should be illegal—and that fetal personhood should be recognized in public law—was the single most important tenet of white pro-lifers’ political advocacy program.

But that was not the case for many African American pro-lifers. Nowhere in Jackson’s article for the National Right to Life News, for example, did he suggest that abortion should be made illegal. Neither, for that matter, did the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church’s resolution against abortion in 1977.

The “setting-apart for God’s work … begins from or even before the womb,” the AME Church said, and “abortion, which represents deliberate destruction of that life created by God, is a violation of that sanctity.” But the AME Church did not suggest that criminalization of abortion was the answer. Instead, it said the church must “seek first to recognize and prevent the circumstances leading to problem pregnancies” and “must also surround each parent and child with love and provide them with concrete spiritual, social, economic and educational assistance.”

This framing of the pro-life issue was strikingly different from the one white evangelical denominations adopted shortly thereafter. When they joined the pro-life cause, they intended to rescue the nation from the evils of Roe v. Wade—and that rescue was inseparable from a political campaign to change the law.

In 1977, when Jackson and the AME Church spoke out against abortion, the pro-life movement had not yet acquired a partisan identity, and many of its leaders were still Catholic Democrats who were sympathetic to the social-welfare framework that Jackson and the AME Church favored.

But in 1980, that began to change with the Republican Party’s nomination of Ronald Reagan, who endorsed the Human Life Amendment. White pro-lifers flocked to his campaign; even many lifelong Democrats who led pro-life organizations were excited by the prospect of a president who endorsed their cause. White evangelicals who were already moving into the Republican Party were especially ecstatic.

In June 1980, in the middle of the presidential election year, the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) adopted a resolution not only denouncing abortion and affirming the sanctity of unborn human life but also endorsing an anti-abortion constitutional amendment. Indeed, a political campaign to criminalize abortion was the central focus of the SBC resolution. “Whereas, our national laws permit a policy commonly referred to as ‘abortion on demand,’” the resolution stated, “we favor appropriate legislation and/or a constitutional amendment prohibiting abortion except to save the life of the mother.”

Jackson did not share white evangelicals’ enthusiasm for either Reagan or the constitutional-amendment proposal. And Reagan frequently denounced welfare programs on the campaign trail, which disturbed Jackson and others of his politics. “As I see it, there is no room in Reagan’s world for us,” Jackson told African American civil rights activists in October 1980.

Shortly thereafter, Jackson decided that the pro-life movement—which had hitched itself to Reagan and the campaign for an anti-abortion constitutional amendment—was not for him either. Still, when he launched his presidential campaign for the 1984 election, he insisted that he retained his moral opposition to abortion even as he defended its legality. “We must never encourage abortion,” he said, even if he did not want the government to stop someone from having an abortion.

This quickly became the prevailing position in Black Protestant denominations such as the AME Church and the National Baptist Convention, most of which had been strongly anti-abortion in the 1970s. “Abortion is usually wrong,” the senior bishop of the AME Church said in 1990, but it should nevertheless be “a decision of the woman and her family and not of the government.”

A minority of Black Protestants, such as Dallas megachurch pastor Tony Evans or the Church of God in Christ (which passed pro-life resolutions in this century), attempted to hang on to the older pro-life framework common among Black Christians in the 1970s. They continued to advocate for expanded health care coverage or positive alternatives to abortion as a way to help the unborn.

Most non-Pentecostal Black Protestant denominations and denominational leaders, though, found it increasingly difficult to say anything against abortion after the mostly white pro-life movement began focusing so strongly on the criminalization of abortion and aligning with the party skeptical of social welfare programs. As the Democratic Party became ever more committed to abortion rights, so did these denominations, both in their official statements and, polling suggests, in the thinking of the average person in the pews.

By the 1990s and early 21st century, some Black Protestants began promoting a “reproductive justice” framework as an alternative to the focus on “choice” that dominated the white-led abortion rights movement. While predominant pro-choice rhetoric emphasized individual freedom, reproductive justice instead focused on health care and empowerment for the poor. In essence, it took the concerns for the poor and marginalized that Jackson had championed in his 1977 pro-life article and channeled them instead toward support for abortion availability.

Today, several major Black Protestant denominations are arrayed against the pro-life cause. Even members who still oppose abortion typically will not support pro-life politics so long as those efforts center on outlawing abortion and are coordinated through the Republican Party.

But now there’s a new opportunity to build a multiracial coalition in defense of unborn life. The predominantly white pro-life movement achieved a major goal in the Supreme Court decision of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, overturning Roe v. Wade three years ago today, launching a new era of abortion politics. Meanwhile, many younger African Americans are leaving the established Black denominations that have given such strong support to the Democratic Party and instead joining multiracial, nondenominational megachurches that are less monolithically partisan. And some Black pastors have adopted views on abortion that are a lot like the one Evans promoted: They want to defend unborn life, but they want to do so as part of a larger, “womb to tomb,” consistent life ethic that includes expanded, government-funded health care and help for women facing crisis pregnancies.

The history of American Christians’ belief and activism around abortion makes clear that there’s more than one way to frame a pro-life political theology. This is how two groups of pro-life Christians can end up in such different places on the political spectrum. For Christians eager to explore new avenues to protecting unborn life post–Roe v. Wade, this history can help us think more clearly about what kind of alliance we’re willing to make with fellow Christians who are with us on core life issues but quite distant from us politically. Will we repeat the political choices of the last century—or will we expand our alliances in the fight for life?

Daniel K. Williams is an associate professor of history at Ashland University and the author of Abortion and America’s Churches: A Religious History of “Roe v. Wade,” which will be released in October.