In this series

(For previous articles in this series, see here and here.)

Journalists have become used to reporting annual disasters at the hajj, the once-in-a-lifetime trip to Mecca that all Muslims are obliged to take if they are physically and financially able. Last year, 1,300 pilgrims died as “lethal heat combined with humidity proved deadly,” one analysis declared.

And 2024 was not an outlier. A total of more than 4,800 Muslims have died in stampedes at the hajj’s Stoning of the Devil ritual in 1990, 1994, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2006, and 2015. Other years have brought epidemic outbreaks, building and crane collapses, and other disasters not unlikely when 2 million people from around the world crowd into a small area.

This year, at least 216 died, with the lessened total due in part to heat protection measures, including extra shade. Without 1,000+ deaths to report, it’s a good time to breathe deeply and explain why this pilgrimage is important in Islam. The starting point is that Muslims have not the Ten Commandments but the Five Pillars. (Some Shiites have different counts, such as seven, but since the requirements are similar, I’ll stick with the majority Sunni listing.)

The first four requirements are as follows: Make a profession of faith (“There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his prophet”). Pray five times each day. Fast in the month of Ramadan during daylight hours. Give to the poor 2.5 percent of accumulated wealth above a specified amount, which at one time depended on the price of cattle, sheep, or camels. (A very rough approximation today might be $30,000.)

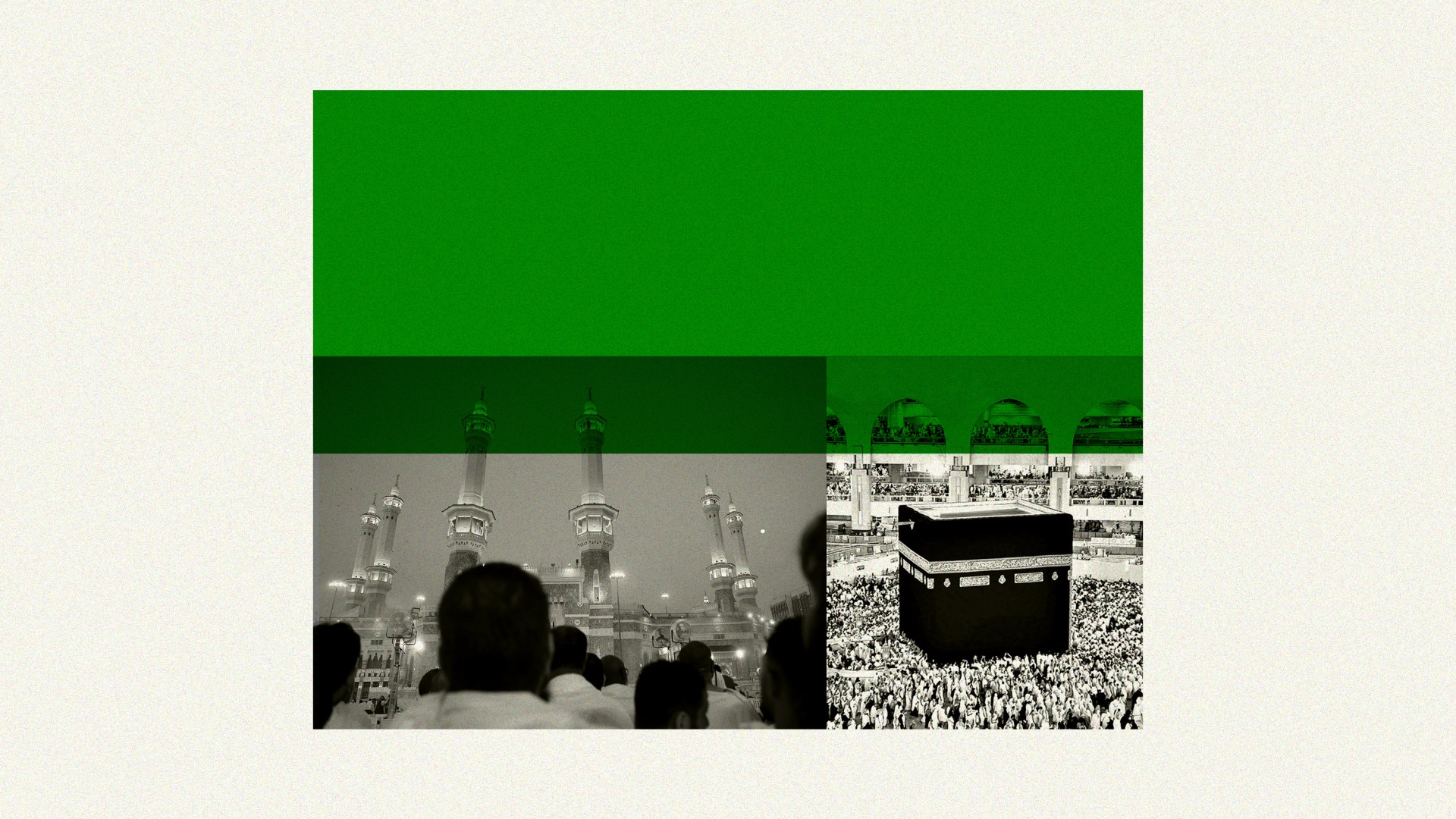

The hajj is the fifth pillar. As one Muslim website declares, “the one who goes for Hajj earns the pleasure of his Lord and comes back with all his sins forgiven. He also earns immense reward that he cannot earn in any other place; one prayer in al-Masjid al-Haram (the largest mosque in the world, located in Mecca), for instance, is equal to a hundred thousand prayers elsewhere.”

To understand what often has gone wrong and what went mostly right this year, start with the 2022 population of Mecca—1,578,722—and the 2020 census population of Phoenix, Arizona: 1,608,139. Almost identical, with a similar desert climate. Ramadan shifts through the year due to Islam’s lunar calendar adjustments, but what if Christians had a requirement to pour into Phoenix as Muslims descended into Mecca last month? What if they had to walk three to six miles in temperatures that rose above 90 degrees, as did Muslims in Saudi Arabia?

It would be doable without many deaths, given Phoenix’s omnipresent indoor air conditioning and the outdoor cooling systems that would be put into place. That apparently is what the Saudis have now accomplished: They boast of the world’s largest cooling system in the Grand Mosque and, through misting fans and other means, vow “to ensure the comfort of all visitors.”

Overall, though, comfort is secondary. Muhammad said a Muslim who goes on hajj “will return … as if he were born anew,” free of all sins. Doing it properly means entering the holy mosque at Mecca with the right foot first and reciting a prayer, then moving in a counterclockwise procession around a stone building that Muslims believe Abraham and his son Ishmael originally built.

In fact, a comfortable hajj might be a problem. Muslim websites say difficulties teach the fear of Allah: Standing in long lines “reminds the pilgrim of the throngs of people on the Day of Gathering. If the pilgrim feels tired from being in a crowd of thousands, how will it be in the crowds of barefoot, naked, uncircumcised people, standing for fifty thousand years?”

Similarly, a ritual of running back and forth instructs Muslims in what Hagar, the mother of Ishmael, did when she desperately searched for water: “Since this woman was patient in the face of this adversity and turned to her Lord, this teaches man that doing this is better and more appropriate. When a man remembers the struggle and patience of this woman, it makes it easier for him to bear his own problems.”

The most dramatic event might be throwing seven pebbles at a pillar (now a wall) to commemorate what the Quran says was Satan’s tempting of Abraham to disobey Allah’s command and not kill his son. Some rituals, like this one, cannot be done anywhere except in Mecca. Whereas Christians emphasize justification by faith, Muslims emphasize justification by works.

The hajj is one of the Five Pillars and thus an enormous opportunity for justification—an opening to a heaven full of sensual pleasure, with saved souls living in blissful gardens with fruit, rivers, carpets, and cushions (Suras 3:198; 4:57; 55:56; 56:35–38; 69:21–24; 79:41; 88:8–16). The one major time of deprivation, the month of Ramadan during which Muslims are not to eat from dawn to dusk, ends with Eid al-Fitr, a three-day festival of fast-breaking marked by celebrations with relatives and friends and frequently the giving of gifts and money to children.

One of Islam’s appeals is the existence of strict dos and don’ts. Each time of prayer consists of units containing set sequences of standing, bowing, kneeling, and prostrating while reciting verses from the Quran or other prayer formulas. The sequences are repeated twice at dawn prayer, three times at sunset prayer, and four times at noon, afternoon, and evening prayers.

Meanwhile, Christians and Muslims debate central issues: If original sin does not exist, why does the Bible tell the stories of so many sinners? Muslims treat the Bible respectfully as the word of prophets but see it as corrupted through the centuries and right only when it agrees with the Quran. Muslims believe that all people are weak but not inherently sinful. Christians do not believe that any works are sufficient to merit salvation, while Muslims believe that having faith in Allah and practicing the Five Pillars make salvation effective.