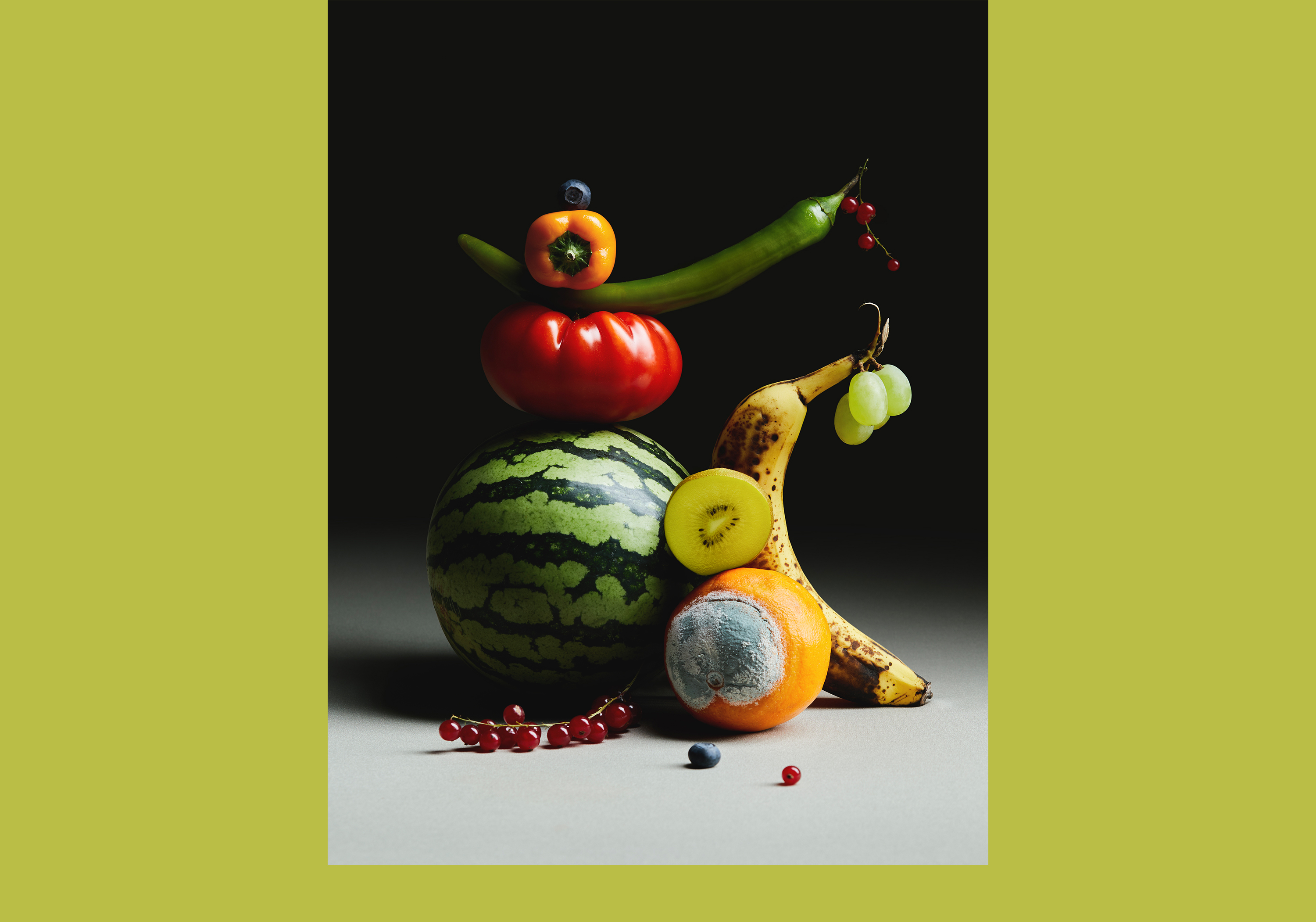

Painting beneath the shifting lights of southern France, artist Paul Cézanne repeatedly turned to a simple composition: a still life with a bowl of fruit. The fruit, he observed, was never the same—each moment altered the scene before him. An apple in the morning would begin to wither by evening. As sunlight moved across the room throughout the day, the bowl’s shadows would change.

Rather than attempting to fix a fleeting moment—to capture some imagined, incorruptible fruit in static time—Cézanne endeavored to compress the fullness of time and space into a single image. His paintings were not about appearance but about essence, a pursuit of what lies beneath the surface. His is the fruit in flux and light, in ripening and becoming, its essence the visible echo of a deeper reality.

Similarly, God’s love resists reduction. God is love—eternal, extravagant, infinite—and this love is made manifest in us as we abide in Christ. We are invited to create with, into, and through that love, which grows in us as another kind of fruit—the fruit of the Spirit.

The fruit of the Spirit is not a plural set of virtues from which to pick and choose. The fruit—like Cézanne’s—is a single, multifaceted, organic whole. The Spirit grows within us something altogether lovely: a restoration of our longing to belong and to become, to be loved and to be known. To steward well and to be satisfied. And amid it all, to be made new in our redeemed humanity.

As an artist (Mako) and an attorney (Haejin), we have had opportunity to reflect on how the fruit of the Spirit relates to beauty and justice and how the two interact with each other.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsIn our work, we have found that beauty and justice are the overflow of God’s love—the mission-critical response of the church to herald the new creation.

Beauty and justice teach us how to be stewards of God’s love in the wasteland, reclaiming meaning over utility and holding to hope amid bleak suffering. They are rebellion, disrupting our transactional world and exposing the lies within. They proclaim that to be human is not merely to exist but to bear the imago Dei—the unique spark of God in each of us.

Just as Cézanne beheld the shifting light upon fruit, we are invited to behold the fruit of beauty and justice, the essential nourishment of humanity.

A young girl rescued from trafficking in South Asia was asked, “Now that you are free, what do you want?” After a brief silence, she replied, “I want to be beautiful again.”

Her answer is both heartbreaking and holy. From a young age, she endured tremendous pain and suffering. Yet she did not ask for revenge or escape. Instead, by wanting restoration, she named the very core of justice: an ache for beauty.

This longing is deeper than ambition. It is a memory of Eden, a yearning for the triune God who made the world out of love, forming us in his image and calling us to participate in the interdependent flourishing of creation. It is a memory of being called tov (Hebrew for “good and beautiful”) by the one who formed us (Gen. 1:31). It is the ache to become fully human again, luminous in love, as we were meant to be.

The injustice this young girl has lived stems, like all injustices, from the original injustice—the one humans enacted against God in Eden. We stole from God’s garden what was not ours, even when abundance was already given to us. Our desire to become more powerful, even godlike, severed our intimacy with the giver of life, marring what God had made tov. Our sinfulness destroyed all flourishing relationships: with God, with each other, and with creation.

Soon after, the second great injustice followed: Cain killed his brother Abel. From that moment on, violence, tyranny, and betrayal took root in history. Humanity spiraled into corruption, and our hearts grew hardened by the desire to control, to possess, to destroy. Beauty withered in the heat of such injustice, and blood soaked into the ground.

We now live in an age of acceleration, where the sacredness of humanity has been buried beneath data, algorithms, and metrics. Our souls, instead of being richly cultivated, have been mined for productivity and profit. We are either useful or invisible; measured, not beheld. We view other people with a scarcity mindset that gravitates toward reductive binaries, casting the “other” as our enemy and turning the outsider into a scapegoat. In the shattered ruins of the Fall, we have lost our capacity to see rightly at all.

Jesus warned us in the Gospel of John that “the thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy” (10:10). In our day, the thief seems to have met his goal. Who will save us from this wretched state?

Crushed for holy justice, Jesus Christ became for us the path to mercy from and intimacy with God, and the portal to the new creation. He took the full weight of our sin in his broken body, shedding his sacred blood and absorbing the wrath we deserved. His wounds became radiant with the beauty of prismatic, redemptive grace.

The antidote to the decay of humanity is, therefore, a spiritual union with Jesus, the one in whom beauty and justice meet. It is to “walk by the Spirit,” bearing the fruit made manifest in “those who belong to Christ Jesus” (Gal. 5:16, 24). It is to seek healing in his wounds (1 Pet. 2:24), so that our scars can display God’s artwork of grace.

Since we started Academy Kintsugi in 2020, the Japanese art of kintsugi has become ubiquitous in popular Christian culture. Many have resonated with the gospel imagery encapsulated in the mending of a broken ceramic vessel with gold powder and urushi (lacquer).

What can’t be captured in an afternoon workshop or a quick sermon illustration, however, is the amount of time the craft requires. Before beginning the work of repair, a kintsugi master will first behold the fragments of a broken dish, sometimes for many years, imagining how it might be whole again. Only after this initial period of envisioning does the work begin, transforming the cracks into the landscape of a healed world.

What if, like the kintsugi masters, the most radical thing we can do today is to slow down and behold the world’s fractures? What if justice is not simply a meting out of verdicts but a making—done with patience, attentiveness, and beauty?

Because of the time-consuming process that I (Mako) use to make my paintings, my work has been called “slow art.” I take pulverized materials—seashells, minerals, and precious metals like platinum and gold—and manually mix them with nikawa, a Japanese glue made from animal hide, before applying the custom paints to create prismatic layers.

The attentiveness of my craft is also my prayer. I work knowing that to create beauty is to echo the Creator, not for the hollow spectacle of momentary attention but for something that endures and is beheld in love. Such beauty resonates beyond the superficial and transactional. It is a gift that generatively expands into the world.

Elaine Scarry in On Beauty and Being Just discusses how beauty awakens us to take notice of our perceptual errors, begetting justice by teaching us to see rightly. To say “This is beautiful” is to make a claim about what is worthy of attention and care. And in the same breath, to say “This is just” is to insist that what is beautiful be protected and stewarded.

Illustration by Daniel Forero

Illustration by Daniel ForeroPsalm 33 tells us, “The Lord loves righteousness and justice; the earth is full of his unfailing love” (v. 5). The biblical vision of justice is God’s loving labor of new creation. It is not punitive but restorative. A cracked bowl—or person—is not thrown out but rather mended. Together, beauty and justice reclaim the fragments of a life and say, “You are not forgotten.” And their work is not complete until the soul can say without shame or fear, “I am tov again.”

Beauty and justice are birthed from a sanctified imagination and lived out while walking with the Spirit. They are the soil in which the fruit of the Spirit takes root and grows, setting things right in light of the present glory of creation and the glory yet to be revealed.

In the place of exile and fracture, beauty and justice empower us to imagine what could grow amid desolation, what shards might look like when wrought whole.

I (Haejin) have seen the fruit of the Spirit growing in abundance in the most unlikely place: an abandoned brothel in India. When a local pastor and I became friends, we chose to walk with the Spirit into that site of generational violence and shame.

With beauty’s imaginative eye, we saw beyond the decay into a future woven with justice: a place of safety, joy, and new beginnings for children born in brothels and for their mothers. In 2018, the building became the Sahasee Embers Center. Over the years, I have seen frightened young children bloom into vibrant youths. I have witnessed shame-faced mothers begin to stand tall again. I have experienced how—like Cézanne’s still-life paintings—the love of God at work in each individual resists all reduction.

In our recent visit to the center, I (Mako) taught an art class to the middle schoolers there. I distributed sheets of paper around the room and began to read J. R. R. Tolkien’s short story “Leaf by Niggle.” As I read, I sketched the meandering lines of a bare tree on a large sketchpad. I told how, during his lifetime, Niggle could not finish a painting of a tree —and how God graciously incorporated Niggle’s one leaf with a “charm of its own” into the new creation.

I asked each child to paint a unique leaf of their own, in any style they wished, and then invited them to glue their leaves onto the tree I had drawn. As the bare branches began to fill in, the students saw how beautiful the tree became when all of them worked together to bring it to life. The collage was a reflection of how beauty and justice were bringing kingdom healing into each of their lives.

Sahasee Embers Center is but one place where God—the only true Artist and Advocate—is at work even this very moment. And he invites us to participate in his resurrection work of imagining, mending, and making, wherever he may call us.

As we walk in the Spirit, may we have eyes to see how God begins to fill the gallery walls of our lives: Here is the collage made by the children of a former brothel; here are the golden lines of a vessel made whole. Here is a portrait of the young girl made beautiful again; here are the scars of the Son of God through whom God is making all things new.

In God’s love, there is enduring beauty. In God’s love, justice flows into our lives. And as we gaze on that love, we find that beauty and justice are not divided but are woven together—indivisible, interdependent, singing in harmony across the canvas of creation.

Haejin Shim Fujimura is principal attorney of Shim & Associates, president of Academy Kintsugi, and CEO of Embers International. Makoto Fujimura is a leading contemporary artist and award-winning author. The Fujimuras have coauthored Beauty x Justice: Creating a Life of Abundance and Courage, to be released in April 2026 (Brazos Press).