Steve Williams was four years old when his family tried to enter a church in Greenford, West London, and some church members stopped them. “You’ll want to try that church over there,” someone said, pointing down the road. “That’d be good for you to go [to] instead.”

“We weren’t the right color,” Williams recalled.

It was 1968. The Williams family had just moved to Greenford. Williams was born in West London, but his parents had emigrated from Jamaica as part of the “Windrush Generation” of Caribbeans who arrived in the United Kingdom between 1948 and 1971 to help rebuild post-war Britain.

His parents didn’t make a fuss when the church shut the door in their faces. They simply walked down the road towards the other church, a nondescript building with a grayish-brown brick exterior and frosty blue-and-white windows.

That church opened its doors to the Williams family. They became one of only two non-white families at Greenford Baptist Church (GBC), but they found a home there. It’s where Steve Williams was baptized, married, and raised two daughters. Today, he’s 61 years old and serves as an evangelist at GBC. He greets newcomers with a beaming smile: “Welcome to Greenford!”

Everybody knows Williams, who owns a steel fabrication factory. He’s been part of the church for 57 years—one of the longest-serving members of GBC—and has watched it transform. Williams is still part of an ethnic minority at GBC, but only because today, there is no “majority” in this church.

On any given Sunday, people of about 35 different ethnicities sing and pray together, sometimes in their own languages. Heads bop about during worship: bald and shiny, or wrapped in African headbands, or topped with straight blond hair, or covered with silvery bobs, or spiked into mohawks, or braided in updos, or haloed by natural afros, or bedecked with jet-black weaves. On stage is a giant mosaic of 28 colorful tiles with the word God painted in the first language of various GBC members—Yoruba, Setswana, Arabic, French, Slavic, German, and more. The church leaders and staff are English, Nigerian, Indian, and Jamaican.

Inside this gray, forgettable building is something vibrant and memorable—a truly diverse congregation that was multicultural before it was cool. GBC has been multiethnic for about three decades—long enough that members don’t seem to realize how extraordinary their church is, until visitors come and gape.

‘This is a traditional church. And that’s never going to change.’

It all started when Greenford Baptist Church’s new pastor, David Wise—a young milkman turned preacher—personally visited each member of the church.

When Wise first became pastor of GBC in 1987, the superintendent of the Baptist Union of Great Britain, an evangelical denomination in England and Wales, warned him, “This is a traditional church. And that’s never going to change.”

GBC was a traditional British Baptist church, with an organ, hymn books, and a strong core of graying, devout women who kept the place running.

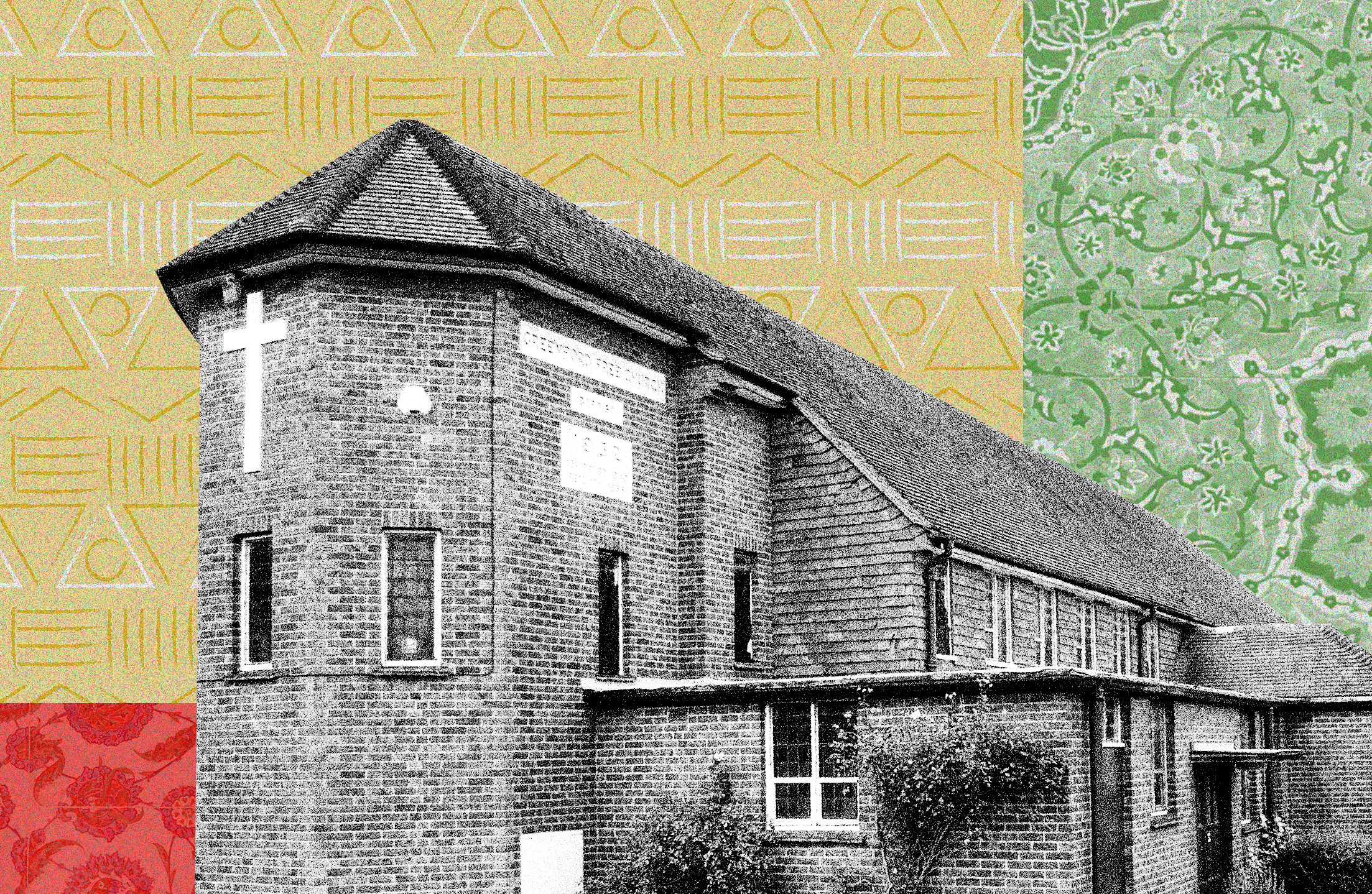

The church began in 1933 as Greenford Free Church. Services took place in a Tudor-style cottage with a gable roof, lattice grids, and square-patterned bay windows. The population in Greenford had jumped from 843 in 1911 to more than 14,000 just 20 years later. Newcomers came for the post-WWI manufacturing jobs, turning the area into an industrial suburb.

When the first air sirens of WWII blared during Sunday service, members unanimously voted to continue worshiping as usual. A year later, at midnight, bombs destroyed their church building, and many church members lost their homes. They met in a farmer’s corrugated iron outbuilding dubbed “The Tin Tabernacle,” enduring leaks and drips until 1955, when they finished constructing the current church building.

When Wise first visited GBC in the ’80s, the church had an unwelcoming atmosphere. Several people told him how unfriendly GBC felt when they visited.

Wise arrived with one main vision: “I wanted to see people share life together, care for each other, so church isn’t just a 10 to 12 o’clock on Sunday morning, but about the rest of the week. I wanted a church that’s a community, a family.”

In 1987, 85 of GBC’s 93 members were white. Six of the eight non-white members were from Jamaica or were children of Jamaicans. There was also an elderly Greek couple who had long since stopped attending. Over the next several years, more foreign-born people started trickling in.

An education in racism

Wise urged members to notice newcomers and welcome them. He modeled hospitality by visiting every member of the church and inviting them over for a meal. But he didn’t take into account the specific challenges immigrants and non-white members faced until he began to hear stories from Black churchgoers.

Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: Getty, Unsplash, Flickr

Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: Getty, Unsplash, FlickrOne young man told him how other students had tried to beat him up because he was Black. He described feeling on edge whenever he passed a group of white boys on the street, and he told Wise about the racist comments he heard in school.

A young Black woman told Wise she constantly felt “lesser” and “didn’t really belong.” Others told him they were spat upon and harassed in the streets.

Wise was appalled: “Racism was a new issue for me, but it had been an issue for the Black people in church, of which I had no understanding.”

David Wise grew up in Hampshire, in southeast England. He lived in a council estate (similar to a public housing project in the United States). Everybody he knew was white.

Then, in 1980, as a newlywed 23-year-old, he and his bride Lesley moved to Southall (about two miles from Greenford), which had the largest Punjabi community in the country. Southall had Britain’s first all-Asian football team, a cinema that played Bollywood films, and shops that sold brinjal, bitter gourd, and chapati flour.

The Wises browsed the shops in fascination, pointing at knobbly green produce and asking how to cook it. They built up their spice tolerance by frequenting eateries where the rest of the customers had brown skin.

At the time, Wise delivered milk for a living, and many of his customers were South Asian or Afro-Caribbean. Every day, a Muslim woman made him chai, sweet and milky and spicy. She would set the cup on top of the postbox and watch him from her house, nodding and smiling. She didn’t speak a word of English, but that slurp of tea was a little exchange across religious, cultural, and language barriers.

The racial tension was as taut as a runner’s calf. In 1976, a far-right gang fatally stabbed an Indian teenager in Southall, but nobody was convicted, which outraged the Asian community. Then one afternoon in 1981, Wise was dropping off milk when some customers warned him: Go home, stay home. Trouble is brewing.

That night, droves of young white skinheads bused over to Southall to attend a concert at an iconic pub, and the local Asian youth braced themselves for a brawl. Hundreds of police officers showed up, cordoning the pub to protect the white youth from the angry crowd, sometimes clubbing the Asians to disperse them, while the white youths shouted racist slogans and made Nazi salutes, smashed the windows of Asian shops, and threw stones at locals. Such harassment was not new to the Asian community, but this time, the younger generation had tired of swallowing their rage. Some threw petrol bombs that burned the pub down. The night ended in fist fights and ashes, with overturned cars and more than 100 people injured, including 61 police officers.

The next morning, on his daily delivery route, Wise surveyed the damage. Dozens of police officers patrolled the streets, and demonstrations went on for days. He was angry about what happened, but to him, it was just another unfortunate event.

“I didn’t have anything to hang it on,” Wise recalled. “I didn’t have any understanding of the history, the background, the British Empire and its legacy. I knew just about nothing.” He could enjoy a spicy curry, but he was ignorant about the daily injustices his immigrant neighbors faced.

In the summer of 1992, five years into pastoring GBC, Wise decided it was time to learn. During his sabbatical, he spent two months in South Africa to “study multicultural churches and structural racism,” according to the minutes of a church meeting.

It was a disturbing and uncomfortable two months for Wise. For the first time, he felt conscious of his skin color. Some weeks, he was the only white person for many miles.

Once, a Black South African invited him to an event. They drove together, but Wise entered the house first, and when the people inside saw his face, they screamed. It was their look of sheer terror that rattled Wise: “They knew nothing about me. … A white person [was] coming into the house, and what did that mean to them? Someone’s going to suffer.”

In Pretoria, he visited a church flagged as a model for multiracial congregations, where both whites and Blacks worshiped together– a beacon of hope in a brutally segregated country. “I’m told this is the best example of a genuinely multiethnic church in South Africa,” he told one Black man he met at that church, and the man laughed.

“This church,” the man replied, “is organized on the basis that white is right. It’s the white way of doing theology, the white way of interpreting the Bible, even down to the food we eat.” Black people, he said, could come along for the ride, but they didn’t have a voice.

Another day, a Black South African took him to visit a Christian radio station near Alexandra, a township in Johannesburg. The staff there were all white. They welcomed Wise warmly but ignored his companion, even though he was standing right next to Wise. “He was just invisible,” Wise recalled. When they got back into their car, the man turned to him and said, “You see how it works?”

Wise returned to London “shell-shocked.” He had awakened to a racial consciousness that he couldn’t un-know, and he didn’t know what to do with it: “I just felt racked with guilt and powerlessness.”

The next several weeks, Wise reflected on his trip to South Africa and penned a report that he sent to leaders of his church and denomination. In that report he asked, “What constitutes [a] non-racial church?”

“It is much more than simply having a mix of cultures represented in the congregation,” he wrote: The work has to be intentional, such as creating multiracial leadership, offering worship and preaching styles that reflect the different cultures of the congregation, and affirming all cultures and peoples at every level.

“We must start by recognizing and treating others as fully human, strongly affirming them along with their culture, heritage and perspectives,” he wrote. “We must open up all sorts of opportunities to them. … We need to recognize that creating trust will not be easy because trust has been betrayed often in the past.”

An attack on one of their own

In 1993, Stephen Lawrence, an 18-year-old Black student, was stabbed to death while waiting for a bus in southeast London. None of the suspects—six white youths—were initially charged.

Four years later, three masked men broke into the house of an Indian family, the Pauls, who were members at GBC. According to the front page of The Baptist Times, the attackers dislocated the father’s shoulder and broke his ribs, battered the mother’s face, and attacked their teenage son so viciously that he needed surgery.

For three years, the Paul family had been enduring verbal racial abuse, racially offensive notes, vandalism, threatening phone calls, and false accusations against their son from their neighbors, according to the spring 1998 edition of The London Monitor. The Pauls had reported these incidents to the police, but they said the police didn’t help. Even after they were physically assaulted, The London Monitor reported, the police response was lethargic.

For many members of GBC, the national news about the Lawrence case in 1993 was background chatter. But the attack on one of their own shocked them and brought home the reality of racism in their backyard. Wise talked about both cases from the pulpit, and the church collectively prayed for justice. Wise also helped campaign for justice for the Paul family and participated in the Stephen Lawrence inquiry.

Wise said the violence against the Pauls “made clear the reality of racism in our local community and wider society to all at GBC.” One White British man told Wise that when the Stephen Lawrence incident happened, it all felt “slightly remote from us,” but when the Pauls were attacked, “you suddenly realized there is an issue within our society.” The man said it caused him to think seriously about how he viewed and treated people of other ethnicities.

The incident had a profound impact on Rotimi Awoniyi, another church member. Seeing the church stand behind the Paul family encouraged him: “There’s comfort knowing that should anything like that happen to me, the church is there to support me. I felt that the church was standing up to injustice. I think if the church did not stand up, there was potential for evil to prevail.” That response to injustice led Awoniyi and his wife to plant deep roots at GBC.

Awoniyi immigrated to Greenford from Nigeria in December 1990 and started attending GBC with his wife in January 1991. They were the first African family at the church. Three decades later, they’re still there. The Awoniyis’ four adult children grew up at GBC. As a long-time leader at GBC, Rotimi Awoniyi helped oversee many of the changes that made the church what it is today.

At his former church in Nigeria, prayers and worship were loud and fervent. Attending a Baptist church in England for the first time was “a bit of a culture shock,” Awoniyi recalled. Nobody clapped, nobody stomped, nobody raised their hands. But he and his wife were touched when some members of GBC called to check up on them, and when Wise invited them over for lunch.

Before his sabbatical in South Africa, Wise had changed GBC from a one-pastor model to a plurality of leaders for whom members vote. He developed an 18-month leadership training course to raise these leaders, and in 1995, Awoniyi was the first African to be voted into the leadership team.

Diversifying GBC’s leadership was a major turning point, Awoniyi said: “People could see that not only is the church diverse, but the leadership team is diverse. They think, I have someone who looks like me at the table who will be able to articulate how I look at things, how I feel about things.”

At the time, Awoniyi had no concept of a multicultural or multiethnic church. He grew up in a church that was made up entirely of Yorubans. Then he heard Wise preach that a local church should reflect the community, that it was unnatural to remain a predominantly white church when the community around it was a mix of Africans, Caribbeans, South Asians, Middle Easterners, Latin Americans, and Eastern Europeans.

Becoming multicultural

In 1999, some Nigerian members led a prayer vigil at GBC that drew upon African traditions. The church held more prayer vigils, and gradually, invited different styles of prayers into Sunday service as well. The church also began holding regular “International Evenings,” in which members brought food, music, and clothes from their mother countries.

The church appointed a part-time prayer coordinator and worship facilitator in 2003 to “integrate and develop multicultural prayer and worship” at GBC. The church invited its members to teach worship songs in their own language and style. There would be a Yoruban number with drums and dancing, or an Egyptian piece in Arabic, or Jamaican reggae-style beats, or a Hindi song sung while sitting on the floor, along with the meditative beats of a tabla drum, bells, and drone sounds. All the lyrics would have English translations.

Wise also changed the way he preached. He pursued a part-time MA in Aspects of Biblical Interpretation so he could preach more effectively to people of other ethnicities. Sometimes he walked around the congregation holding out his mic, asking people for relevant experiences and perspectives based on the scripture passage that Sunday.

Once, someone who had fled Muslim persecution in their home country made derogatory comments about Muslims. But often, such congregational hermeneutics helped broaden and deepen the congregation’s understanding of God’s Word. For example, while studying a passage in Exodus about hospitality, a refugee from Iraq shared how his village welcomed strangers.

Another significant change was the structure of Sunday service. In March 2004, GBC lengthened its service from about 75 to 150 minutes. Before, service ended strictly at a certain time so people could hurry home to their own activities, but the new service structure gave them more time and freedom to be flexible. The sermon was longer. They added congregational prayer during worship time, in which people shared testimonies, celebratory events such as birthdays and anniversaries, and prayer requests, then pray out loud together.

In between worship and teaching time, they took a break for tea and coffee, and members would chat, welcome newcomers, and pray for one another. Once a month, they had lunch after service. This new structure inspired more connection, creativity, and spontaneity.

The demographics at GBC rapidly changed during those years. In 1995, about 20 percent of church members were nonwhite. Ten years later in 2005, the number had grown to 55 percent. By 2014, about two thirds of the church members were nonwhite. Membership grew from 129 in 1995 to 195 in 2014.

‘It’s in our DNA now’

By the mid-2000s, GBC had gained a national reputation. People across the country came to visit, while conferences and churches invited Wise to speak. In 2010, the first Mosaix conference took place in San Diego, a once-every-three-years gathering focused on the multiethnic church movement.

That optimism has sputtered since. Many nonwhite churchgoers have left the once-championed multiethnic churches. In 2021, Christianity Today published a cover story by Little Edwards titled “The Multiethnic Church Movement Hasn’t Lived Up to Its Promise.”

“Multiracial churches often celebrate being diverse for diversity’s sake,” she wrote. The number of multiethnic churches have risen in the past two decades, but many have failed to create a space that’s equal, inclusive, and equitable.

Wise, who retired as pastor of GBC in August 2019 and currently consults with churches around the United Kingdom, have also seen many churches in the UK dissolve into conflict and division as they seek to become multiethnic. Wise found that dealing with racial issues at GBC was sometimes like battling the invisible wind—you knew it was there, you could feel it, but you couldn’t quite pin it down.

Sometimes, that wind looks like a woman calling Wise after Awoniyi prayed during Sunday service for the first time, complaining that she couldn’t understand a word he said. “That’s complete nonsense,” Wise told me. Awoniyi has a slight accent, but his English diction is precise and clear. Soon after, the woman left GBC for another Baptist church that’s mostly white.

Others also left, sometimes with vague explanations as to why. “People didn’t say, I’m leaving because there are Black people here,” Wise said. “They would say they don’t like the way the church is developing, or the worship.”

In one particularly difficult case, Wise and the church leadership dismissed some long-time worship leaders. Wise said they were hanging onto the old version of GBC and resisting efforts to include nonwhite singers and different cultural styles. It was a tense, stressful time.

For about 30 years, Wise used the imagery of tapestry to cast a vision for GBC, inspired by a paraphrase of Colossians 2:2: “I want you to be woven into a tapestry of love” (MSG).

We are all God’s workmanship (Ephesians 2:10), he preached, through which God reveals himself. God himself is the weaver of the tapestry of GBC, and even the smallest detail on the tapestry adds distinct texture and beauty to the overall art. Everyone contributes; everyone adds value.

The Sunday I visited GBC, they welcomed a new member into the church. Afsaneh is a refugee from Iran, with limited English, and chose GBC as her church because of its inclusive diversity.

That morning, Afsaneh smiled shyly as the current pastor Warren McNeil, who had been going through the Bible with her one-on-one using Google Translate, passed her the mic. “You can speak in whatever language you feel comfortable with,” he told her. She said in English, “Thank you.” And then she continued in Farsi, expressing more gratitude through the language of her heart.

Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: Getty, Unsplash, Flickr

Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: Getty, Unsplash, FlickrWhen she returned to her seat, Mala, the Indian woman sitting next to her, grasped both her hands, and they squeezed each other, smiling. Mala had been regularly checking up on Afsaneh, helping her with all the practical things she needed to settle into a new country.

I talked to 10 members of GBC, nine of them members for more than 20 years. To hear them talk about their church, they are clearly proud of it, yet they also seem slightly surprised that people marvel to see them intermingling in a kaleidoscope of accents and dress and hairstyles, instead of self-segregating by ethnicity.

“I’ve taken it for granted,” said Elizabeth Harries, a slim, blonde staff leader who has been attending GBC since she was six. “We’re unaware of what we’ve got here. It’s not until we go outside or someone comes and asks questions and then you kind of go, ‘Oh. I don’t know. It just happened!’” Of course, Harries knows it didn’t “just happen.” But it’s an indication of how organic multiculturalism has become for GBC.

“It’s in our DNA now,” McNeil told me. “It’s natural for us. We don’t even think about it because we’ve been on a 30-year journey.”

It doesn’t mean cultural miscommunications don’t happen sometimes. In 2018, McNeil made a faux pas: He needed help serving communion, so he gestured to a woman from an African country, using his index finger to make a beckoning sign.

What he didn’t realize was that in her culture, that was a derogatory gesture, something a master would do to a servant. It triggered some memory in the woman, and McNeil noticed she stopped showing up at church after that. When he realized his mistake, he visited her, got down on his knees, and asked for forgiveness. It was merely a cultural misunderstanding, but McNeil knew what it meant for a white man, especially a pastor of authority, to kneel before a Black woman. She forgave him immediately, and they talked it out. Recently, McNeil was at her house, drinking tea and laughing with her and her husband.

McNeil is still struggling about whether GBC can become a tapestry that enfolds everyone. At times, he wonders if there’s room for everybody’s culture except his. It seemed so effortless and celebrated for someone like Awoniyi to express his Nigerian culture, to suddenly break out into a Yoruba song in the middle of worship, but what White British culture can he so proudly and boldly express, without worrying if it’s too … colonial?

“In our society at the moment, being white is damaging. It’s, ‘How dare you? You’re why we’ve got all the problems in the world,’” McNeil told me. “So I feel less than. I have found myself very much struggling to express my own culture.”

In his painstakingly conscious efforts not to be arrogant, he wondered if sometimes he’s gone to the other extreme into white guilt, trying so hard to step into other people’s shoes that he’s lost his own: “Then I don’t become properly part of the tapestry at that point.” He was starting to feel resentful, and that was a dangerous place to be as the pastor of a multicultural church.

The pandemic provided a spiritual refuge for McNeil. He used the solitude to process his thoughts and emotions before God, and then process it out loud with his wife and trusted close friends.

For Steve Williams, the church evangelist and son of Jamaican immigrants, it was the reverse. Growing up, all his friends were white. All his girlfriends were white. He didn’t like being different, didn’t think he should be different. As a kid, he told his mother not to cook him Jamaican food anymore. He wanted what the other kids ate. No more curry goat; he wanted sausage rolls.

Growing up, he sometimes returned home with scrapes and bruises because a gang of white kids had jumped him on the bus or on the streets, mistaking him for South Asian. He started resenting South Asians, blaming them for why he couldn’t walk the streets without looking behind his back. It wasn’t until the last two decades, as he grew with the church in embracing different cultures, Williams realized how much of an identity crisis he had, and the prejudices he had developed against South Asians. He too had to bring all those internal struggles to God.

Such are the countless instances of invisible, internal work that shaped the community of GBC. The image of a tapestry church sounds beautiful, but in real life, it was often uncomfortable and messy. Not everybody enjoys the sporadic dancing that sometimes happens during worship, while some people feel straightjacketed when the worship and prayers are somber and slow. Some people feel comfortable grabbing people by the face with both hands to show affection, while others would rather shake hands from two feet away.

But it’s also a taste of heaven on earth, an imperfect image of Revelation 7:9–12, in which “a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language” stands before the Lord and worships in one voice.

Sophia Lee is former global staff writer at Christianity Today who is now a stay-at-home mother. She lives in Los Angeles.