(This is the third in a series. Here are the first and second articles).

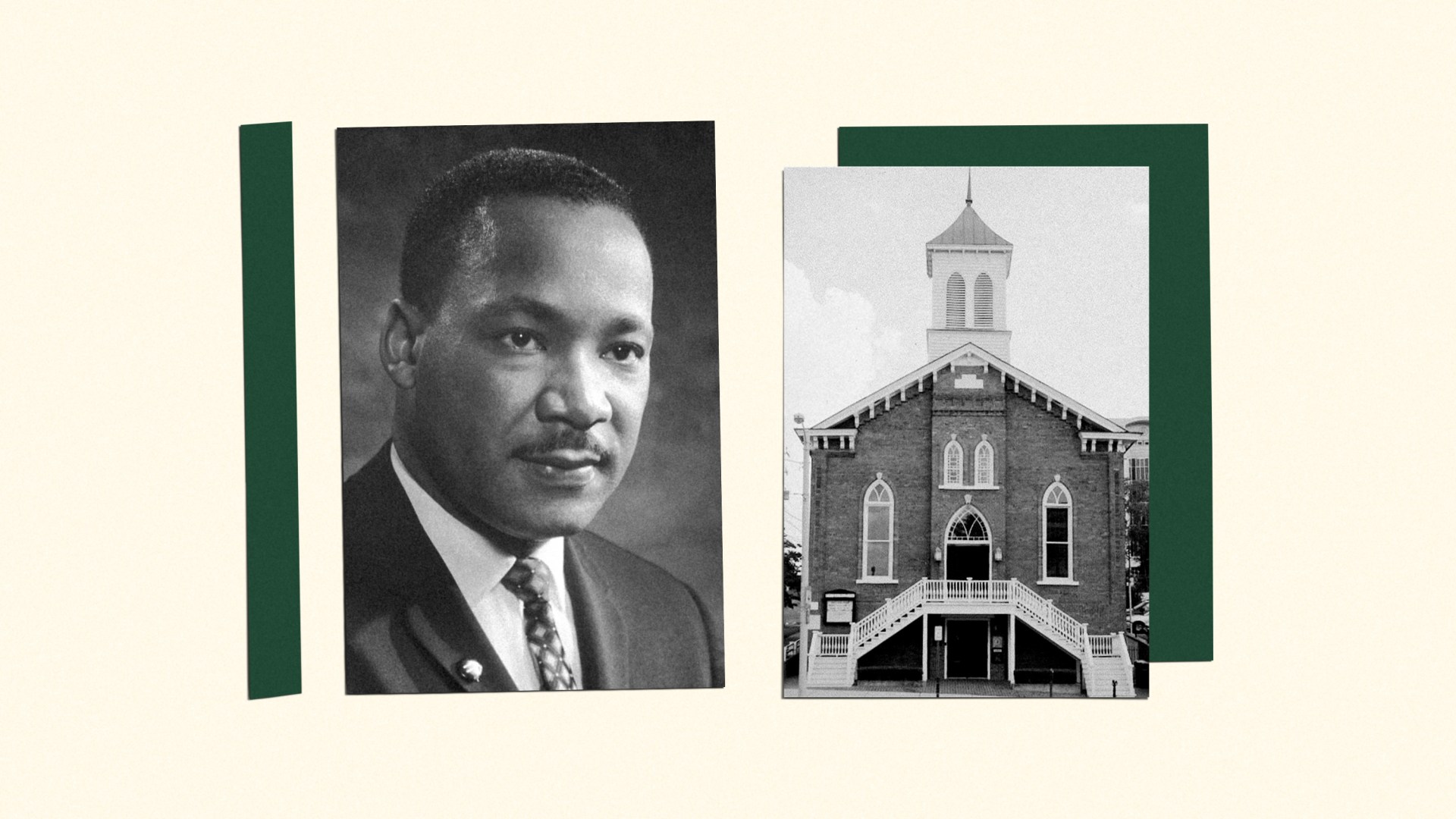

Americans know a lot about Martin Luther King Jr., but the evangelical legacy of the church he pastored in Montgomery, Alabama, is a lesser-told story.

Like many African American churches, Dexter Avenue Baptist Church (now Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church) grew from the evangelical tradition of the antebellum era. Yet the congregation’s history and development reflect the Black church’s complicated relationship with the movement.

For the third installment of this series, I wanted to write about why many Black churches with evangelical roots and beliefs don’t identify with the label today. I’ll be exploring that question through the story of Dexter, which has played a seminal role in American history.

The roots of the influential congregation date back to an enslaved preacher named Caesar Blackwell, who, during the Second Great Awakening, drew large crowds by preaching the gospel. At that time, spiritual life in Montgomery reflected the religious landscape of the country before the Civil War. The city had fervent revivals, a passion for evangelism, and Christian communities focused on spreading the message of the Cross.

Often, these practices crossed the color line. The number of Baptists in the city, for example, grew in part because of revival meetings that brought together white and Black people. Some interracial mission work emanated from the conviction that everyone was a sinner in need of God’s grace and saving redemption. But at the same time, Black people (and a growing number of Christians among them) were living under the bondage of slavery and racial oppression.

Dexter, for its part, began in Montgomery’s First Baptist Church, a white congregation that opened its doors to Black converts swayed by evangelical preaching before the start of the war. When Black congregants grew numerous enough to form their own congregation, they met with supervision in the basement of the church and, for the first time, elected their own leaders.

After the Civil War, newly emancipated slaves were encouraged by the 13th and 14th amendments and anticipated that old marks of inferiority, such as segregated church seating and white paternalism, would dissolve.

However, when leading postbellum theologians and white church leaders doubled down on racial hierarchy, a growing number of Black Christians left racially mixed congregations and formed their own churches. Among them were the Black congregants of First Baptist Church. In 1867, they established the first independent Black Baptist church in Montgomery. Then about ten years later, some members split off and formed Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. The congregation soon selected Charles Octavius Boothe, a prominent and influential preacher, as its first pastor.

Boothe, born as a slave, was representative of the devout Black Baptist community around him as well as the leaders who shepherded Dexter in the decades to follow. He first encountered the gospel through his family, including his grandmother, whom white and Black people alike sought out for prayer due to her fervent spiritual life. Boothe’s family life, however, was interrupted when he was abruptly sold to a white man at the age of six.

Evangelical passion for sharing the gospel came in tandem with the harsh realities of slavery. Still, the true “gospel story,” Boothe said, “bound me to it with cords which nothing has been able to break.”

When the Civil War ended, Boothe dived into ministry as a part of his newfound freedom and became an ordained minister. This period presented an opportunity for the Black church to lead the African American community in establishing its own institutions, embracing racial uplift and planting churches that had all the marks of evangelical faith. Boothe joined with other newly independent Black Baptists and formed a convention that planted churches and sent missionaries throughout the war-torn South and abroad, both to share the gospel and to do works of charity.

After a short tenure as the head of Dexter, Boothe left to pastor another church and began serving as the president of Selma University. Dexter continued its “evangelical ministry” into the 20th century, church historian Zelia Evans said. But over time, the church’s theological scope widened with the advent of the Social Gospel.

The 20th century brought on fierce debates between theological modernists (who were often aligned with the Social Gospel) and fundamentalists. Those disagreements culminated in the fundamentalist-modernist controversy, which ushered in a wave of denominational splits between the two camps. But for the Black church, things were more complicated. Black Christians saw both groups had something valuable to offer.

Fundamentalists like Dwight L. Moody sustained their passion for evangelism and their concerns for doctrinal faithfulness. But they were not as concerned with the bleak reality Black people faced in the post-Reconstruction South. Their disengaged response to the rise of Jim Crow laws and the uptick in racialized violence, supported by a segment of white theologians, was distasteful and hypocritical. As a result, a significant number of Black churches rejected the racial politics played by many fundamentalists while supporting the movement’s doctrinal opposition to theological liberalism.

Many of Dexter Avenue Baptist’s early 20th-century ministers attended Virginia Union University, a popular training spot for Black preachers that exposed students to the Social Gospel. When they entered ministry, some pastors—such as Robert Judkins and those who immediately came after him—advocated for racial equality while maintaining their evangelical orientation. They upheld the authority of Scripture and were bold about preaching the gospel, sending out evangelists and missionaries at home and abroad.

When the Civil Rights movement began to pick up around the middle of the century, the church was drawn further into the Social Gospel. Leaders like Vernon Johns and Martin Luther King Jr. emphasized America needed to overcome its centuries-long racial caste system. In their sermons, they never contested Dexter’s doctrinal commitments. However, they made it clear that orthodox beliefs alone would not improve their predicament as oppressed people. Black Christians, as a result, directly confronted racial injustices (including through a prominent boycott organized at the church).

As white evangelicals separated themselves from the fundamentalists in the mid-century, leading evangelicals like Carl Henry did disavow fundamentalists’ inability to call out the ills of society. But not everyone got on that train. The National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) rejected invitations from Black clergy to participate in civil rights marches or direct action campaigns. Meanwhile, the National Council of Churches, a predominantly mainline ecumenical body that currently includes some Black denominations, took them up on the offer. The result was that white evangelicals missed out on participating in Black Christian history during one of its most defining moments.

For many African American believers, the NAE’s approach to evangelical Christianity did not fully capture the ideals of faithfulness. Evangelicalism, as portrayed by those who proudly carried its name, strove for intellectual orthodoxy and a passion for evangelizing the world, but it only timidly applied that same faith toward social issues. Over time, organizations like the National Black Evangelical Association emerged to fill the void. But for the most part, African American Christians never came to embrace evangelical as a self-descriptive title.

In the decades following the Civil Rights Movement, evangelicalism’s association with political conservatism has not done much to convince the Black church to reassert its evangelical roots. Nor have the developments of new theological movements, such as Black liberation theology and womanism, that have created often unspoken factions within some major Black denominations. Nonetheless, studies, such as Marla Frederick’s Between Sundays, show that though many (if not most) Black laypeople do not identify as evangelicals, they embrace the authority of the Bible and the tenets of the wider evangelical tradition.

Today in Montgomery, the antebellum roots of the evangelical tradition still show at Dexter Avenue Baptist, which holds services every week. The church is affiliated with the Progressive National Baptist Convention, a denomination that emphasizes social justice and estimates its membership at 2.5 million.

The congregation did not make a representative available for an interview on its current-day activities. Its public-facing materials show an embrace of the “Romans Road” form of evangelism, faithfulness to the Scriptures, and Christ-centered charity work. Still, the modern-day descriptor of evangelical isn’t always a useful label for congregations that see racial equity as an aspect of gospel fidelity. The term may describe the church’s roots. But the contemporary understanding of the label in the US doesn’t describe its present.

Jessica Janvier is an academic whose focus crosses the intersections of African American religious history and church history. She teaches at Meachum School of Haymanot and works in the Intercultural Studies Department at Columbia International University.