Look, the legislative staffer said, all Ken Paxton has to do is go down to South Texas and say women are “crazy,” and he’ll have the divorced men’s vote in the bag.

That’s the clean version of his remarks. The unedited version seemed to win some grudging respect at his table. The four other 20-something men in coat and tie laughed. One shook his head, a mild reproof.

Their tongues (and collars) had been loosened by sipping cans of Lone Star in the shadowy recesses of the Cloak Room, a famous basement bar just south of the Texas Capitol.

They were relaxing at the end of a steamy August day. One of the off-duty staffers queued up another Freddy Fender song on the classic jukebox near the entrance. The twang of “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” began to play, and the five talked about the question launching a thousand debates among politically involved Texans: Who will win what could be one of the most expensive Republican primary races in US history?

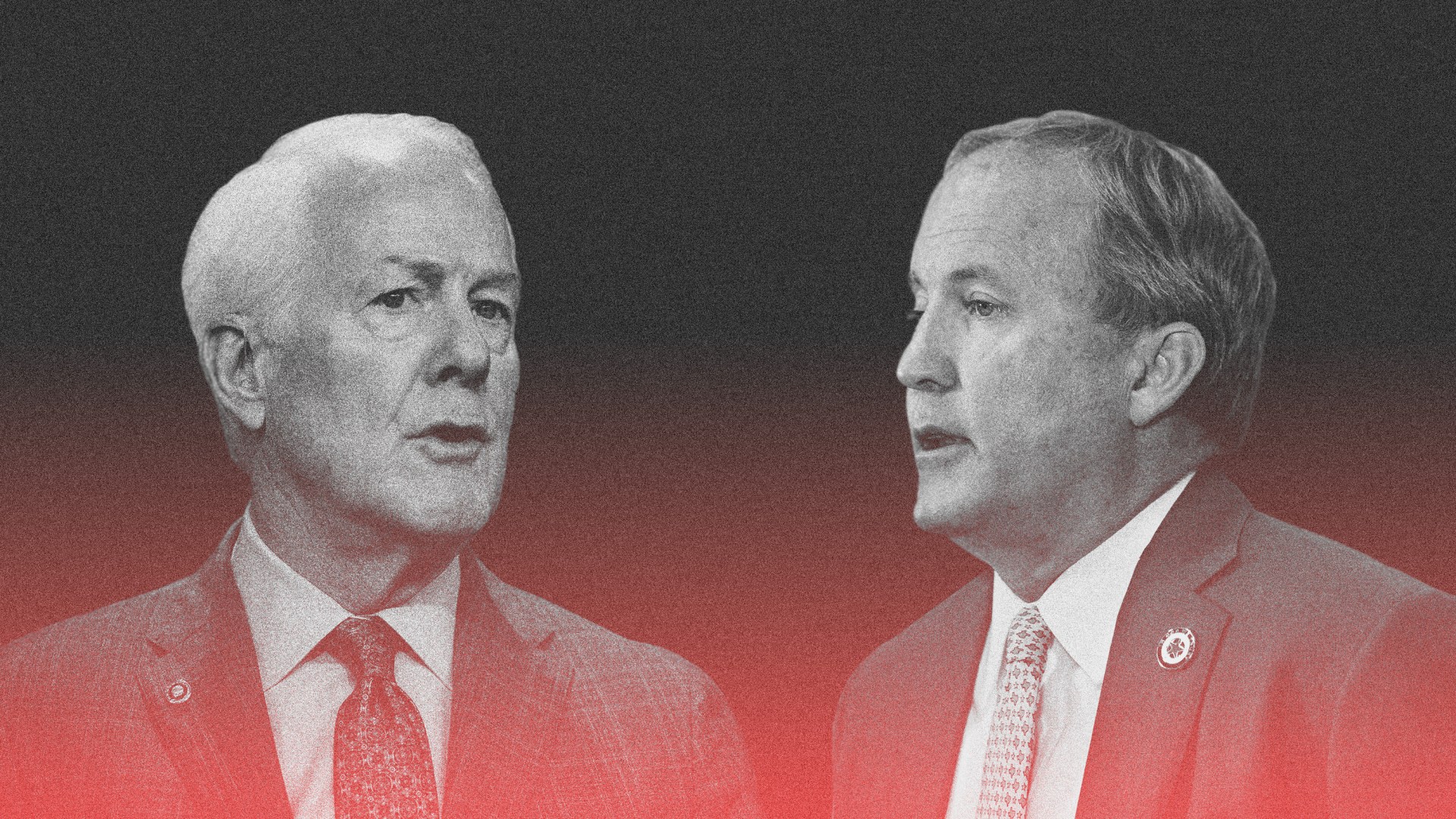

Attorney General Paxton, a family values advocate embroiled in a contentious divorce suit, was indicted in 2015, impeached in 2023, and acquitted by a 16–14 vote of the Texas Senate. Nevertheless, Paxton has had an edge in polls regarding a likely GOP primary race next March against incumbent senator John Cornyn, a conservative thought to have a much better chance than Paxton does of winning against a Democratic opponent next November.

Both Cornyn and Paxton have worked closely with President Donald Trump and are vying for the coveted White House endorsement, leading the exasperated president to tell reporters, “I wish they weren’t running against each other,” and to say he would make a decision down the road. A primary fight would be incredibly expensive, if it’s anything like past races: During Ted Cruz’s and Colin Allred’s Lone Star face-off in 2024, the candidates raised nearly $200 million.

I spent a week in Texas to get a sense of the race, interviewing government staffers, pro-life activists, Texas political insiders, Christian voters, and Cornyn. Paxton’s team did not respond to requests for an interview.

One place to start was Austin’s Ann and Roy Butler Hike-and-Bike Trail, a ten-mile loop past gleaming downtown skyscrapers and a haze of no-see-ums breeding on the Colorado River. Hardcore sun worshipers ditched their shirts for calisthenics at an outdoor gym to do pull-ups and crunches. Others jogged solo. One white-haired man sped by on a bike, blasting Maroon 5 on a speaker loud enough to make passersby wince.

Just a few blocks away at the Texas Capitol, bristling with lawmakers and protesters during a special session, the talk was of flood disaster response and, more controversially, a partisan gerrymander that had drawn the ire and riposte of the governors of California and New York.

But no one at the Hike-and-Bike Trail was eager to talk politics. The calisthenics enthusiasts declined pausing their workout to talk about the Senate race. Another couple, both Democrats, seemed ashamed to admit they weren’t yet paying attention and “needed to get educated.” Luke, a 26-year-old landscaper working on the trail, said he doesn’t know much about either candidate and isn’t sure yet how he’ll vote.

The trail was a stark contrast with the sleek, modern lines of The Austonian, a luxury condo close to the Capitol. Cornyn, on a brief stop there while crisscrossing the state, spoke with me in a sterile-looking conference room.

Cornyn has been campaigning since 1984, and it’s a grind for him and his wife, Sandy, who travels with him. Cornyn credits her for saving him from having to camp out in bachelor-pad digs popular among his colleagues or sleeping in his office.

The two have been married for 46 years. Whether to campaign again was a joint decision. When he posed the question to her, she was matter-of-fact: “When I told her what the alternative was, she said, ‘You have to run.’”

Incumbent Cornyn has served in the Senate since 2002. He’s a courtly, 73-year-old politician who on the Hill is known among his colleagues as more workhorse than showhorse. He’s more likely found hammering out the finer details of a bill than making appearances on the Sunday-show circuit. In the 1980s, Cornyn was a district court judge in San Antonio’s Bexar County. From there, he served on the state’s Supreme Court for seven years.

A book by Thomas T. Fox about Cornyn’s political rise dubs him a “quiet strategist.” For much of his career, that approach has paid off. He sits on some of the most important committees: Judiciary, Foreign Relations, Finance, Intelligence. During the last Congress, GovTrack ranked Cornyn as the second-most-prolific lawmaker, with 19 of the bills he introduced becoming law. During the two years before that he headed the Senate leaderboard for the number of laws enacted.

But that’s part of why some Texans are less than pleased with Cornyn. In 2022, Cornyn was a high-profile negotiator on a bipartisan gun law following the deadly Uvalde, Texas, elementary school shooting.

The bill did not restrict access to guns for law-abiding citizens. It did offer, among other changes, funding for increasing school security and incentives for states that do implement red flag laws. During that time, at a state party convention in Houston, hundreds of Republicans booed when Cornyn took the stage.

The response showed how political winds have shifted. The center of gravity on the right has moved from the hawkish, pro-business, fiscally conservative Bush-dynasty-era Republicans to the gloves-off, Make America Great Again populist right. This newer right is quick to criticize any overtures to the other side. Bipartisanship reads as betrayal.

“Nobody is going to confuse me with Donald Trump,” Cornyn acknowledged—but that hasn’t stopped him from working closely with the president. A super PAC supporting Cornyn blasted the airwaves with an ad campaign highlighting that Cornyn “votes with President Trump over 99 percent of the time.”

Cornyn is betting that voters will consider his long record when making their decision. But for the GOP base, “quiet strategy” has fallen out of favor. Has Cornyn?

His opponent, Ken Paxton, certainly is making that case. Paxton, who has been attorney general in Texas since 2015, has built a reputation as one of MAGA’s most aggressive attack dogs, from leading a charge challenging the 2020 presidential election results to suing the Biden administration over immigration policies. He wants Texans to send a politician more self-consciously molded in the MAGA-warrior archetype.

In an advertisement, Paxton said the senator betrayed the America First movement when in May 2023, asked about Trump’s chances in 2024, Cornyn said, “Time has passed him by.” Cornyn later endorsed Trump.

Paxton’s biggest challenge in the race is his history of legal and personal controversies. Allegations of adultery were something of an open secret that did figure in the 2023 impeachment debates.

Paxton admitted to staffers in 2018 that he’d had an affair, but said it was over. The trial examined whether Paxton had acted corruptly. He faced allegations of bribery and abusing the power of his office. The prosecutors alleged that Paxton misused the powers of his office to help Nate Paul, a donor and real estate mogul, in part because Paul had hired the woman Paxton was seeing. At the time, his wife Angela Paxton’s support was one reason the Senate acquitted him of those charges. Angela Paxton, also a state senator at the time, attended the trial but abstained from voting.

Paxton’s lawyer during the trial, Tony Buzbee, said the allegations weren’t relevant to the case. “Imagine if we impeached everybody here in Austin that had had an affair,” he said during cross-examination. “We’d be impeaching for the next 100 years, wouldn’t we?”

Paxton has faced allegations of corrupt acts over his years of public service, but he’s never been convicted of a crime. Last year, he struck a deal with prosecutors to avoid a trial in a felony securities fraud case nearly a decade in the making. An agreement on community service and payment of nearly $300,000 in restitution led to the close of the case last year. Federal investigators also closed a whistleblower case this year concerning corruption allegations from his former aides.

Scandal hasn’t prevented him from winning reelection, and Paxton has lambasted the allegations as political witch hunts. But his marriage has been a casualty: This summer, Angela Paxton filed for a divorce. On social media, she said “biblical grounds” and “recent discoveries” led to the move. In the divorce filing, she cited adultery as a reason for ending the marriage and noted the two had ceased living together as spouses since 2024. They had been married 38 years. They helped found a nondenominational evangelical church in Frisco, Stonebriar Community Church, and would later attend Dallas megachurch Prestonwood Baptist Church, according to Texas Monthly. Paxton has attributed his success to getting “the Christian community out to vote.”

Cornyn, who was raised in the Church of Christ, is not the type of politician to wear faith on his sleeve. But in our conversation he did connect faith with the thorny questions this campaign has raised: “I don’t hold myself out as the gold standard on anything. But I do think that’s one of the important issues that’s going to be decided here: Does character still matter in politics?”

Cornyn added, “Everybody makes mistakes. The most important thing is, what do you learn from those mistakes? Or do you just keep repeating them over and over and over again, which seems to be the case for Mr. Paxton?”

Greg Jeffers, a Christian voter who attends an Anglican church, said that years ago he would have assumed evangelical voters would be turned off by a candidate undergoing a divorce due to cheating. He’s no longer sure that’s true, with national politics casting a long shadow over state and local matters. “The question is, is Trump the only one immune from the sort of criticism that would normally take out a politician? Or is Paxton also?”

He said that in his circles Christians are turned off by Paxton’s cloud of scandal. So is one conservative Christian group, Texas Values Action, which rescinded an endorsement of Paxton after news of the divorce broke. Texas Values Action president Jonathan Saenz said the revelation concerns a lot of Christians, with many asking, “If he’s not faithful to his wife, will he be faithful to us voters?”

Texas Values Action has worked with both Paxton and Cornyn and has not so far made a choice for the primary. Saenz said, “Many Republican, Christian, conservative voters still want to feel like they’re not being asked to overlook … or sort of lay down their Christian beliefs when they go to the ballot box.”

The state is more religious compared with the US population at large. According to Pew Research Center, 67 percent of Texans identify as Christian, with nearly 30 percent of those identifying as evangelical Protestant. Another 5 percent identified as historically Black protestants.

While Paxton is weighted down with scandal, Cornyn struggles with, well, vibes. “He seems a bit detached from your average grassroots voter in the state of Texas,” Saenz said.

Perhaps the perception of detachment strikes more acutely because of the contrast with Cornyn’s Senate counterpart: “Every other night Ted Cruz is probably on Fox News or some other national news broadcast.”

Still, Cornyn’s record of bipartisanship and “pleasant gentleman personality” would come in handy in a general election, Saenz said.

Paxton’s bomb-thrower approach has plenty of fans, particularly among those most likely to show up for the primary. “Activist Christian groups that are more engaged in the political and electoral process, those folks tend to favor fighters,” said Cal Jillson, political science department chair at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. “They’re willing to argue that God has always used flawed vessels for his purposes.”

Texas political insider Michael Quinn Sullivan is not endorsing either candidate, but he praised Paxton’s work as the state’s top law enforcement official: “Ken Paxton did a great job suing the Biden administration”—more than 100 times.

Sullivan publishes Texas Scorecard, which maintains a directory of lawmaker ratings and provides right-of-center content. Texas Scorecard censures non-MAGA politicians, and everything at its headquarters in the Austin suburb of Leander seems oversize, from four large-screen TVs to the flags—a “Come and Take It” and “Don’t Tread On Me” among them—draping the walls.

The big, airy space is a fitting setting for Sullivan, who at six foot four towers over everyone in the office and keeps his large hound dog, Freddy, nearby. Both are very hospitable, though Freddy’s friendly overtures are somewhat smothered once Sullivan puts him on a leash.

The Texas Monthly and The Dallas Morning News have deemed Sullivan “the enforcer” and the state’s most influential unelected Republican. He dismissed concerns that Paxton’s ethical questions will cost Republicans a Senate seat: “When the plumber came to my house this morning, I didn’t give him a theology test. I didn’t quiz him on the state of his family. I wanted to make sure he had his plumber’s license and that he had the tools to do the job right.”

Sullivan, who identifies with the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA), said many of the criticisms of Paxton—like that he’s the “more flawed” candidate Democrats want to go up against—are attempts to play “17D chess which doesn’t actually apply to anything in the real world.” A coffee table in the Texas Scorecard office features a chess set in shades of brown. Not a piece is out of place.

Sullivan’s line in defense of Paxton may account for his lead against Cornyn in the polls: nearly 15 percentage points in May. But that was before the divorce news and before Cornyn’s allies began an aggressive advertising campaign. Recently, according to RealClear Polling’s average, Paxton’s lead was only two percentage points.

Cornyn’s allies are betting that once voters learn more about Paxton’s flaws and Cornyn’s long record, the incumbent will take the lead.

Joe Pojman, founder of Texas Alliance for Life, said Cornyn’s quiet strategy is still needed in politics: “He is not flashy. He is substantive. He is not superficial. I think that that will prevail, as it did the last two times.”