The chattering buzz arrives in the morning like a party. Mothers greet one another, laughing over their mishaps along the muddy miles they walked to get to this clinic in Bundibugyo, at the western edge of Uganda. A fortunate few came by boda, a rugged motorcycle that tackles footpaths while several adults and kids squeeze onto the seat.

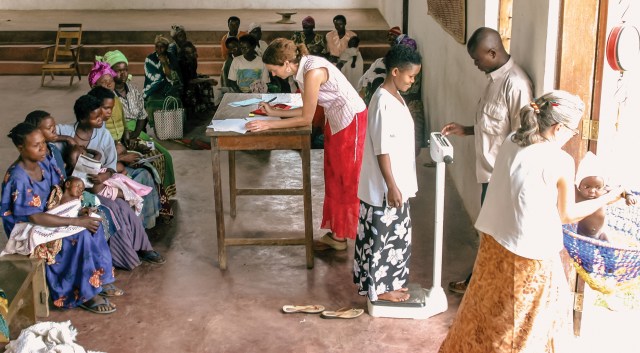

The women untie infants and toddlers from colorful kitengi cloths that snug the babies to their backs, then crowd inside the clinic, where a dozen wooden benches are arranged beneath a tin-roofed porch. More patients queue up in the main intake area. They stack handwritten medical records on a table. They undress their children and place them to be weighed in a crocheted rope basket dangling from a scale.

The mood is nothing short of festive. As a missionary and pediatrician who lives and works here, I see it all the time.

Clovis, a dedicated member of the clinic’s nutrition team, enters each child’s name in the register while I talk to the first few women in line. Mercy’s nine-month-old son can’t yet sit, and his thin limbs make his head look heavy.

I ask if he’s her first baby, guessing she might have had trouble breastfeeding. “Yes,” Mercy offers, “but he was born after seven months, not nine.”

Photo by Scott Myhre

Photo by Scott MyhreMore of her story emerges: Mercy has given birth prematurely three times. The first two babies died at birth. This third infant is her only survivor. A blood smear test shows his small body teems with malaria. Like all these mothers, Mercy is seeking help and leaning into the hope around her.

Another mother in line, Agnes, wears a smile that belies her struggles. Two of her six children are in our nutrition program. She crosses back and forth over the Uganda-Congo border between her relatives on one side and her husband’s family on the other, subsisting from their small gardens. Like Mercy, Agnes kept searching for solutions, and her confidence grew when her kids started eating. Now the younger one, licking his fingers, is eating a locally made peanut paste we provide many of the children who come to the clinic.

Malnutrition is sobering and sorrowful. But our clinic is a place of hope and action—it’s a place of provision in a little stretch along the Albertine Rift that runs west of Africa’s Lake Victoria.

The rift is a long line of mountains, volcanoes, valleys, and lakes that mark the boundary between ancient tectonic plates slowly fracturing the continent. It is also a border between countries and realities, one that marks the historical limits of colonial powers and that is frayed by armed conflict and greed for resources.

Miseries incubate in our remote, rainforest region. There’s a strain of Ebola named for our district. Bundibugyo is one of the poorest parts of the country, where wages average $3 a day.

Agnes’s cross-border migration for medical and nutritional aid puts her among thousands of Congolese who have been uprooted from villages attacked by the Allied Democratic Forces, a rebel group operating on both sides of the border. Our region is contested and contradictory: both densely populated and wildly biodiverse, rich in rare minerals and poor in disposable income, bursting with potential for growth yet struggling to thrive.

Our circumstances are similar, in many ways, to those that fed Israel’s skepticism in Psalm 78: “Can God really spread a table in the wilderness?”

God’s people here are enmeshed in all the challenges of this wilderness: the hunt for drinkable water, secure homesteads, and food. They also struggle to ensure survival of the youngest and oldest, peace with neighbors, a sense of place and purpose, and to be seen by God.

But I think this is the perfect place for God to prepare a feast.

Our small cross-cultural mission group has for more than three decades invested in concrete answers to wilderness dilemmas. That includes schools, churches, Bible translation, and youth development. And importantly, child nutrition programs in western Uganda, eastern Congo, and central Burundi. We live locally in simplicity and partner with churches and communities that are making all things new. That includes little bodies beset by hunger.

Some of the children arriving for today’s clinic will qualify to be admitted to inpatient wards for further treatment. Many will receive a peanut butter–like paste called Plumpy’Nut, which we source through various United Nations programs, or fortified milk or packets of flour to take home.

Sometimes, however, we can’t get what we need, and our community improvises supplemental foods of its own.

Peanuts and soybeans grow in these jungle parts, also moringa trees with nutritious leaves. All these can be combined to make a tasty peanut-based puree. (Plumpy’Nut is free, but when we purchase peanut paste made locally, we are helping to grow businesses.) Gardens of sorghum grains and maize stalks added to the soybeans yield heaps of complementary protein that can be dried, roasted, and milled into a blend that families use to cook a wholesome porridge.

Serge, as our ministry is known, enables these communities to fill the hunger gap at rural hospitals and clinics. There the food is portioned out, wounds are bandaged, and ills are treated. One of us examines a child whose frailty has not yet responded to care, while another peels boiled eggs for the day’s arrivals, while the mothers listen to a Bible story and a nutrition lesson.

This is what a feast in the wilderness looks like.

Along this African rift, hunger has a thousand faces. Visit any one of the programs and you will find countless variations on the stories of Mercy and Agnes. A child may be orphaned and unfed because his mother lacked access to a postpartum blood transfusion. Another might start breastfeeding but wean prematurely because his mother has become pregnant again, bowing to pressure to solidify her marriage ties or beset by the unavailability of appropriate family planning. A family might be underfed because their ancestral garden has been subdivided too many times over the generations. Another may be fighting tuberculosis. And still another may be born to a family struggling to feed the children after paying school fees.

By the time 10 or 20 new children enroll in the day’s clinic, their collective stories hold the weight of a broken world.

Childhood malnutrition, injustice in the distribution of land, family conflicts, untreated disease, droughts, floods, and wars. Blame the world, the flesh, the devil, or all the above, but it’s the smallest humans who suffer.

Jesus delights to bring life to the least likely places, and it’s his story that brings hope in these stories. On earth he wandered just such a wilderness and fed those who came to hear him.

From his first miracle providing wine for a wedding; to multiplying the five loaves and two fish; to his final moments with his followers around the Passover meal, sharing food was central to the community Jesus was creating. The table became a window on the unseen realities he spoke of. Jesus called himself the bread of life, his body given and broken to save us all.

Photo by Scott Myhre

Photo by Scott MyhreTo relieve suffering and to fix the harm that mars creation is a holy and worthy calling that our mothers, aunts, neighbors, nurses, and nutritionists at Bundibugyo embrace. Tying such tastable truth to the substance of eternity, to the life we arc toward, tethers Jesus’ work and the acts of his followers to the hidden glory we long for. These meals are some of God’s “nodal points of relationship,” as Miroslav Volf and Ryan McAnnally-Linz call them in their book, The Home of God—material things that connect humans to one another, to creation, to life, to God, to home. East and central African cultures grasp this meaning deeply: Love is never just a concept but always an embodied action.

In the African rift, in spite of 21st-century evils, a cultural tie to Eden persists. At the site of abutting tectonic plates, languages and stories intersect: a diversity of gifts in the body of Christ for creating a new table.

Photo by Scott Myhre

Photo by Scott Myhre Photo by Scott Myhre

Photo by Scott MyhreWhether outsiders who come to this remote area or those who find themselves here by birth, all bring their loaves and fish. Some bring clinical training, donors, or just a determination to see change. Others bring gardening techniques, communication skills, or courage to innovate. Jesus intentionally commissions this mixing of humanity because none of us adequately embodies the answers alone. Those sent to serve and those who receive blend the nuts and grain, the stethoscopes and explanations, the alertness to acute need and the willingness to take risks.

Together, we create feasts that daily broadcast this truth: the status quo of hunger and injustice is not the end of the story. Jesus continues to call us into the wilderness, where he provides both the tangible necessities of survival and the behind-the-veil goodness of his presence. He shows the church how to embrace places of paradox. In these rural, marginalized places with their limited options, the table is spread with peanut butter and pencil stubs, vitamins and malaria medicine, Bible teaching and gardening tips.

One day, the lion will lie down with the lamb. For now, a few groups of nurses meet mothers, people who speak one language stumble through another, workers with two dozen years of schooling engage patients with two, families who have nothing to spare take in an orphaned niece and tell their story to people who have the internet at their fingertips. Like sparks, ideas fly, hope shines, and everyone moves a step closer to home.

Real home, where the feast never ends.

J. A. Myhre is a pediatrician and missionary serving in Africa with the ministry Serge. She lives with her husband in Bundibugyo, Uganda, and is the author of the Rwendigo Tales series for youth.