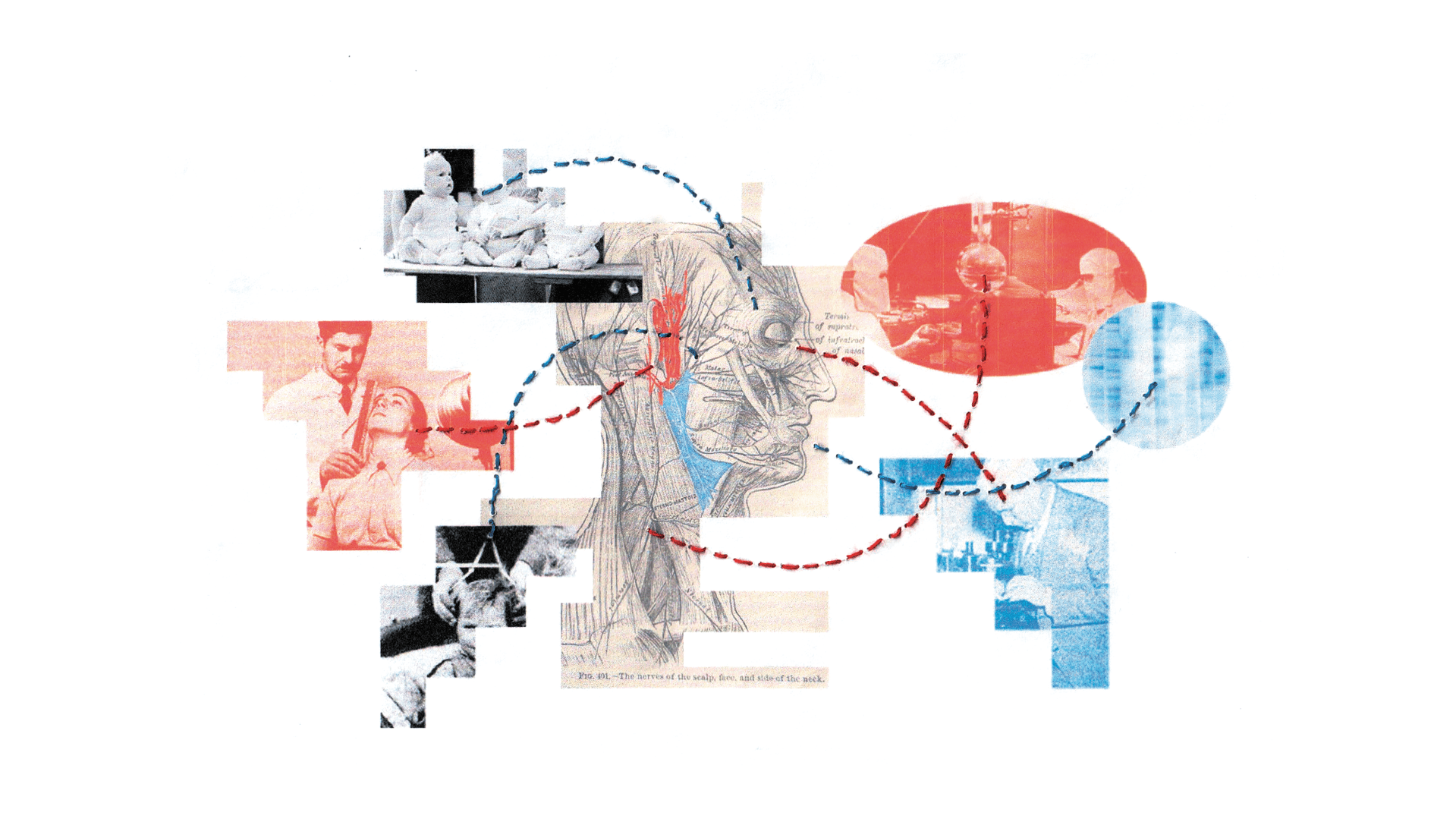

Around a hundred years ago, America’s pastors received a curious invitation. A prominent national organization proposed putting their pulpit skills to the test. But the judges wouldn’t reward displays of biblical fidelity or apologetic brilliance. Instead, formal honors (and cash prizes) would flow toward preachers willing to walk a precarious theological tightrope.

Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement

Oxford University Press, USA

296 pages

$59.45

Christianity affirms God’s image in all people. This makes it an awkward fit with the notion that some image bearers, deemed drags on society, should cease being fruitful and multiplying. Yet the sermon contest inspired pastors across the land to twist themselves into pretzels, which must have delighted its sponsor: the American Eugenics Society.

From a contemporary perspective, it boggles the mind that prominent eugenicists would court religious allies. Most perplexing, perhaps, is the fact that their overtures did not return void.

In her 2004 book Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement, cultural commentator Christine Rosen (currently a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute) asks why Christians were pulled into this grotesque orbit. Her answer lies in rediscovering a time when eugenics occupied the cultural mainstream.

In its early-20th-century heyday, the movement gathered a loose but formidable coalition of scientists, reformers, and public officials who sought “rational” control over family formation. Worried that unchecked breeding would “pollute” the gene pool, they envisioned humanity’s finest specimens of health, intelligence, industriousness, and character crowding out their supposed inferiors. Leaders spoke frankly about racial purity, cataloging favored and disfavored traits that mapped with suspicious ease onto favored and disfavored groups.

This eugenic impulse had its softer and sterner forms. Some proponents thought education, moral suasion, and public policy nudges could suffice to stop the “unfit” from reproducing. Others recommended government coercion. If the diseased, dissolute, and other “defectives” wouldn’t gracefully exit the stage, they said, the state would have to yank them off by force.

Under the hardliners’ sway, elected bodies launched campaigns of involuntary sterilization and restricted interracial marriage, among other abuses. Over time, eugenics became a byword for crude ethnic chauvinism and pitiless assaults on human rights, all underwritten by junk science. Nazi Germany supplied a chilling exclamation point, clarifying where the whole sordid business could lead.

Early on, however, eugenics supporters didn’t sound like cruel sadists. They espoused high-minded, humanitarian sentiments, sunnily investing science with near-limitless potential to spur social betterment. Christians inspired by social gospel thinking who already traveled in these progressive circles were primed to lend sympathetic ears and voices.

As Rosen notes, her book mainly concerns the church’s “modernist” (or liberal) wing rather than the fundamentalist opposition that arose in response. It revolves, then, around characters I typically hold in low esteem, like arrogant social engineers and Christians who discern God’s kingdom unfolding in every trendy cause. I’ll admit to an undignified relish at the prospect of watching these types embarrass themselves.

And sure enough, Rosen delivers a parade of lowlights. Consider Albert Edward Wiggam, a lecture-circuit fixture who fashioned an updated Ten Commandments, complete with zeitgeisty appeals to “The Duty of Measuring Men” and “The Duty of Preferential Reproduction.” Or the sermon contest participant who mocked one family maligned in eugenicist circles as symbols of intergenerational dysfunction. “Surely,” he claimed, “the Kingdom can never come in all its fullness among a people descended from the Jukes.”

Yet Rosen balances cringeworthy moments with more generous appraisals. She credits most Christian eugenics supporters with acting in good faith. She acknowledges that they grappled with serious social problems. And she argues plausibly that liberal pastors restrained more radical bedfellows.

These moderating tendencies manifested along a key axis of eugenics debate over the relative influence of heredity and social environments. Many eugenicists imagined propensities for criminality or philandering passing from parents to children as mechanically as eye color. Pastors often questioned that deterministic view, even before real genetic scientists buried it.

Liberal pastors’ scientific skepticism had a moral corollary. Some hereditarians denounced welfare and charity, believing they wasted resources on people locked in genetic prisons of deficiency and vice. But these pastors continued promoting compassionate outreach, believing a humane society could lift lower classes up rather than weeding them out.

Despite these grace notes, I finished Preaching Eugenics in a censorious mood. Not because of Rosen herself, who clearly abhors eugenic quackery even as she pursues historical objectivity. Rather, because the church, for all its benevolence toward the eugenically “unfit,” could have been bolder. It could have taken a sledgehammer to the whole misbegotten project—namely, the doctrine of original sin. Often tainted by its association with dour pessimists and puritanical scolds, this doctrine is in fact profoundly ennobling. As with affirming that all people bear God’s image, affirming our common fallenness puts us on a radically equal plane. It defeats any attempt to mark some as unsuitable for life together—and condemns any aristocracy assigning itself that task.

Scripture says plenty about traits that further or frustrate individual and social righteousness, of course. We’re called to fight disorder and decay. But to adapt Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s penetrating words, the line between fitness and unfitness runs through each person’s heart.

The central characters in Preaching Eugenics betray little awareness that the figures they anoint as civilizational prototypes are cut from the same warped timber as everyone else. In a couple instances, Rosen notes the fretting that attended studies documenting low birthrates among descendants of the Mayflower pilgrims. Had the fretters read Romans 1? Did they suppose that American folk heroes somehow stood apart from the rest of sinful humanity?

Rosen quotes one contest entry that epitomizes the eugenicist delusion. Reinterpreting the Good Samaritan story, the preacher fantasizes about an age when Christians won’t have to comfort victims because robbers won’t be born in the first place. It’s all too reminiscent of present-day murmurs about abortion lowering crime rates, biotechnology’s seductive vision of custom-designed offspring, or dark rumblings on the outer fringes of immigration and fertility debates.

In Deuteronomy 7, as Moses prepared the Israelites to the enter the Promised Land, he issued a humbling reminder: God chose them out of love, not because they were mighty or meritorious. What qualifies us to choose our neighbors any differently?

Matt Reynolds is senior books editor at Christianity Today.