Cameras switch on and monitors come alive as pastor James Mwita steps behind the pulpit and into the camera’s view at St. Peter’s Methodist Church. It’s Sunday morning in a quiet neighborhood in Langata Constituency, Nairobi, Kenya. The hum of a laptop signifies two congregations—one sitting in the pews, the other present behind pixels.

Mwita’s sermons now reach thousands across Kenya and the globe, and other pastors have similar goals. With nearly 72 million mobile devices and over 56 million active mobile data subscriptions for a population of 57 million, Kenya is among the ten most digitally connected countries in Africa. TikTok, YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram have become fertile ground for Christian content.

But this digital revival comes with its own challenges. As the gospel goes viral, questions have arisen about the depth of community and accuracy of doctrine presented on social media.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, churches like Christ Is The Answer Ministries (CITAM)—an English-speaking church in Nairobi—restructured entire ministries to thrive online. The church offers YouTube devotionals and virtual forums attracting Kenya’s youth demographic: 18-to-35-year-olds. In its research the church found that over 20 million youth barely attend church, creating an opportunity to reach young Kenyans digitally.

Meanwhile, TikTok-famous pastors like Victor Kanyari have stirred controversy for earning thousands via livestreams with gimmicks and “indecent content.” Kanyari has earned over 400,000 Kenyan shillings (about $3,090 USD) on TikTok.

Kanyari is a preacher based in Nairobi and the founder of the Salvation Healing Ministry. His ministry operates independently of any denomination, and he has not yet disclosed any formal ordination credentials.

Jeffter Wekesa—another online pastor without public ordination records—runs a fully virtual church from his Nairobi home. He preaches exclusively over YouTube and TikTok. His social media ministry earns between 100,000 and 300,000 Kenyan shillings (about $770–2,320 USD) per month. His teachings from his living room focus on hope amid crisis and revolve around Kenya’s socioeconomic struggles—unemployment and youth unrest.

Mwita said sometimes people online worship in pajamas and forget service times. “They think, ‘I’ll watch it later,’” he explained. “But they rarely do.” He warned that a consumer approach to online church can create a culture of “passive consumption rather than active participation.”

Some online-only ministries have minimal oversight or theological scrutiny. Without accountability from elders and deacons, online preachers risk spreading incomplete or unbalanced theology. Church leaders in Kenya say members must be equipped with doctrine to withstand false teaching.

The 2023 Shakahola Forest incident in Kilifi County, Kenya, exposed how unregulated teachings can lead to catastrophic outcomes. Pastor Paul Nthenge Mackenzie of Good News International Ministries—an apocalyptic, online, fringe church—persuaded followers to retreat into the forest to starve to “meet Jesus.” Over 400 believers, including children, died from starvation, suffocation, and strangulation.

Government investigators confirmed Mackenzie used twisted interpretations of Scripture—preaching against education, medicine, and even national identity systems—as part of a doomsday narrative that encouraged isolation and blind obedience. A forensic psychologist testified that many followers exhibited “empathy delusion,” even assisting in the deaths of their loved ones as an act of faith.

Other online ministries struggle with distance in emotional matters, especially during moments of grief or counseling sessions. Mwita has used virtual discipleship to keep a British teenager engaged with church and help an American woman through personal crisis, but he recognizes the limitations of online ministry.

“Pastoral care through a screen is not always enough,” Mwita admitted. “You can’t read tears over a livestream.” Many rural members who come to depend on livestreams face unstable internet connections or lack digital devices altogether, further isolating them from church.

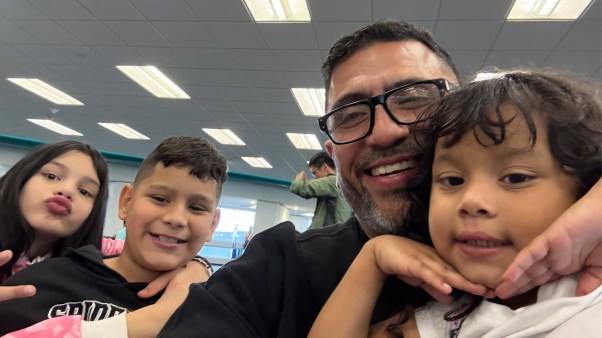

Mwita, hoping to build relationships, trains pastoral leaders to follow up with digital attendees, offers personal spiritual support, and guides new Christians through discipleship materials. St. Peter’s also holds Zoom and WhatsApp Bible studies, virtual Q and A forums, and small group prayer meetings.

“We send weekly SMS reminders, devotional PDFs, and WhatsApp videos. We treat our online audience like members, not spectators,” he added. But Mwita warned of spiritual shallowness: “It’s easy to become a consumer rather than a disciple—to scroll instead of seek.”

Mwita’s antidotes: teach about spiritual disciplines, encourage digital detoxes and screen-time balance, and blend online and in-person worship. “Online ministry can transform lives,” he said, “but only if we lead with intention, care, and community. Otherwise, we risk having churches with screens but no souls.”