The street preachers are not all wrong, you know.

We always have grounds to suppose the world is ending. Or a world, at least. Democracy, free speech, Kentucky’s topsoil—any system, institution, or resource that requires tending remains at risk of negligence and then destruction.

My friends wouldn’t label me a cynic, but I do try to stay levelheaded about these things. I am acquainted with the ways of weeds. I’ve seen good marriages choked by sins of omission as well as commission. Things fall apart, and nature abhors a vacuum. A little folding of the hands to rest, and there goes your car’s transmission.

Entropy abounds, yet few of us are content to sit by and watch the world burn. We feel responsible to do something to put things right, to stave off what little chaos we can. For Christians, this sense of obligation stems from Scripture’s many injunctions to seek justice, love mercy, promote peace, care for the poor and vulnerable—in short, to love our aching world. There are so many causes that would enlist our loyalties, so many sorrows we might alleviate. The challenge, of course, lies in deciding what to do with the time we have left.

Perhaps the last thing you’d think to do is pick up a book. What good is reading at the end of the world? Why read when you could volunteer at a soup kitchen, call your state representatives, or pull weeds?

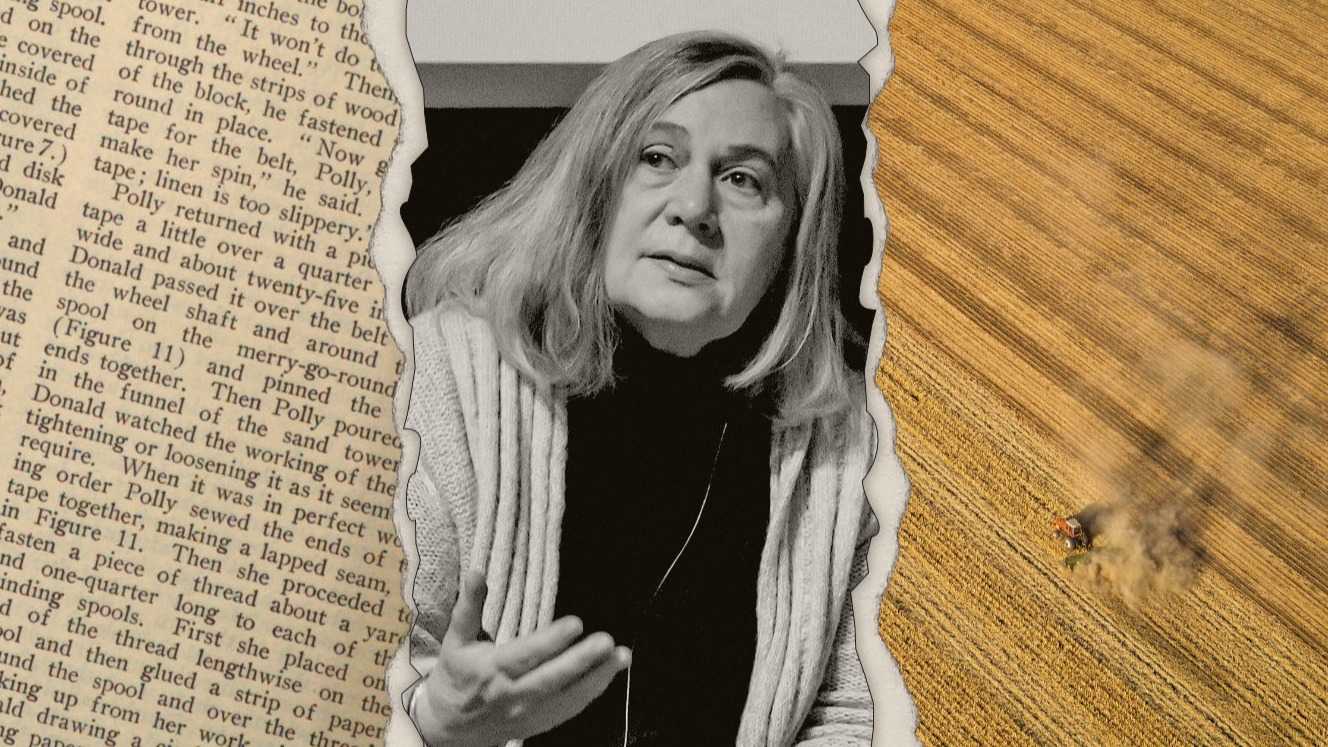

For help parsing such questions, I recently contacted one of the most prodigious readers I could think of: Marilynne Robinson. Few living authors have so profoundly probed and disclosed the human condition as Robinson. In both her essays and novels—including the Pulitzer Prize–winning Gilead—she helps us consider the intrinsic dignity of life and language in the face of catastrophe, and the hope it takes to keep reading.

In an email interview, Robinson shared about her recent reading interests, art and politics, artificial intelligence, Shakespeare, and more. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Polls continue to indicate that Americans are reading fewer books for less time. Perhaps our Founding Fathers would be alarmed, but should we be? Are there goods inherent to reading books that can’t be enjoyed through other media?

A book is an ingratiating thing. It is actually yours, so long as it is in your hands. You invest memory in it as a physical object. You can mark it up, return at will to a place you have found moving or problematic, and be reminded that you change as a reader, even while enjoying the pleasure of memory. Nothing is going to go wrong with it. It never needs a charge. You can buy a book and shelve it as a promise to yourself, an aspiration.

I am not surprised that innovative forms of information and entertainment have their appeal, their own beauty. But the book—the codex—has been around for 2,000 years at least, for very good reasons.

What’s one book that preoccupies your mind these days? Why do you think that is?

My interests are always a little unusual, however predictable they may seem in retrospect. I’m reading, in translation, an essay on English law probably written by Henry de Bracton, a 13th-century jurist. I’m looking at the intertwining of humane impulses with autocratic ones to try and understand how liberal democracy arose, how its adversaries survived within it, and how these adversarial views are rationalized and encoded in earlier law.

Many “new” enthusiasms are really the resurgence of old habits and antagonisms. They are irrational, in other words, and they have an entrée into political discourse because they are also traditional.

It seems we may be on the cusp of an artificial intelligence revolution. Many have voiced concerns over the implications of generative AI for human agency, labor, and creativity. Some artists are advocating for a New Romanticism, claiming “it’s 1800 all over again.” What do you make of these developments as a writer? Where might we seek wisdom for facing AI in the years ahead?

It’s hard to distinguish a “revolution” of this kind from an effective sales campaign. It is true that vast amounts of money are being poured into this technology. It is also true that it is not becoming more reliable or necessarily returning improved profits. So much has been invested in it that more investment is needed to cover potential losses, which would certainly stagger the economy if or when the whole boondoggle collapses, leaving environmental disasters behind.

As far as creativity is concerned, AI can make coherent rehashes of randomly collected data. Artists should address their work to people who want more, who want meaning, for example.

In your article “Imagination and Community,” you argue that democracy and other large-scale communities require “imaginative love” for others with whom we may deeply disagree. Do you believe fiction can nurture such love?

Yes, if it chooses to.

Speaking of democracy, you recently described America as “two nations” contending for authority, resources, and cultural influence. How else can writers contribute to cultural reform without succumbing to mere culture war or propaganda?

Writers can produce work that is simply good in itself—sound, beautiful, attentive to the felt experience of life. We have let too much be absorbed into “politics.” In practice, politics can be beautiful in their own way when they are based on courtesy, good faith, and worthy motives. But ideally, they are a backdrop for the important work of inquiry, creativity, advancement, and just living life.

We have made a kind of religion of politics, a low-ceiled, incurious, angry one with nothing of the beauty or moral seriousness that dignifies authentic religion. At the moment, politics is very much overburdened by significances that it is not suited to carry. Art should be art, religion, religion, and politics, politics.

Turning from politics to literature, what has a writer like Shakespeare taught you about generosity?

An interesting question. He certainly exemplifies empathy. There is hardly anyone on whom his attention rests who is not given a moment of grace. I have been thinking lately about how Shakespeare was among the earliest writers in the English language to take on high subjects and popularize them further by staging them in a public theater.

An old poet in one of Shakespeare’s late plays, Pericles, says that in the deep past, songs were sung “to make men glorious.” I take him to be speaking for Shakespeare when he wishes he could have more time, and “spend it for you like taper light.”

Shakespeare, of course, knew what he was doing, giving people what was their own and would be more their own for his glorious gift. This was also the realization of his own nature as a poet, not in a self-aggrandizing sense but in the pleasure of the bond realized in providing people with their story in their language, made glorious. This is a transcendent generosity, full of the blessings of giving and receiving.

After my exchange with Marilynne, I checked out Pericles from the library and read it for the first time. The nautical play follows Pericles, Prince of Tyre, as he flees assassination by a depraved king and sails the perilous Mediterranean to rescue his wife and daughter from disaster. In the end, however, it is not Pericles who saves his family but a series of happy coincidences, which we are meant to see as divine interventions.

Early in the play, the then-bachelor Pericles is shipwrecked at Pentapolis, where friendly fishermen have just conveniently caught his shield and armor in their nets. This enables him to enter a nearby contest for the hand of beautiful Princess Thaisa. Six knights present their shields with a different emblem and phrase. Pericles goes last, his armor rusty and battered. His shield shows “a wither’d branch, that’s only green at top” and the motto, In hac spe vivo, or “in this hope I live.” Intrigued, Thaisa falls for Pericles, the two are promptly married, and they sail off into the next tempest.

Books often behave like Pericles’s shield, washing up on the shores of our lives in times of need. A book may sit unread on my shelf for years—an old aspiration or a gift from a friend—before some mysterious providence moves me to tolle lege, to “take up and read.”

Certainly, this was the case with Robinson’s novel Gilead. The book had been circulating among my peers for some time before I got around to reading it in the fall of 2018, having recently moved back to South Dakota from New Jersey. A proud but vocationally bewildered seminary grad, I found comfort in the steady voice of her character John Ames. Here was a man sharp enough for Barth and Herbert yet humble enough for Iowa!

In one remarkable passage in Gilead, Ames recalls a country church that had been struck by lightning and burned when he was a young boy. After searching the charred ruins for Bibles and hymnals, his father helped pull down the building in the rain. Ames watched from a nearby wagon with the other children as the adults worked, the women passing out food:

I remember my father down on his heels in the rain, water dripping from his hat, feeding me biscuit from his scorched hand, with that old blackened wreck of a church behind him and steam rising where the rain fell on embers, the rain falling in gusts and the women singing “The Old Rugged Cross” while they saw to things, moving so gently, as if they were dancing to the hymn, almost. In those days no grown woman ever let herself be seen with her hair undone, but that day even the grand old women had their hair falling down their backs like schoolgirls. It was so joyful and sad.

The protagonist remembers the scene as one of communion, which makes me wonder: Can a book be a means of grace? I don’t mean the sacramental means of grace, but a particular paperback (or hardcover) expression of God’s general providence, no less, by which he feeds us as from his fatherly hand. Grace sanctifies and strengthens us to endure the pitiless storms of life. It aims to make us glorious. Likewise, good poems, stories, and essays encourage the kind of slow interiority necessary for virtue at the end of the world.

Nothing so mundane as reading can prevent an AI apocalypse, environmental degradation, or the collapse of civilization as such. Even so, perhaps reading can remind us, as Robinson suggests, that creation’s fate does not finally depend on human will or technique, but on God, who has mercy.

Reading thus trains us in hope. To pick up a book in this world is to raise a shield bearing “a wither’d branch, that’s only green at top.” In hac spe vivo.

Cameron Brooks is the author of Forbearance (Cascade Books, 2025). He holds an MA from Princeton Theological Seminary and an MFA from Seattle Pacific University, but he calls South Dakota home. Visit camerondavidbrooks.com for more.