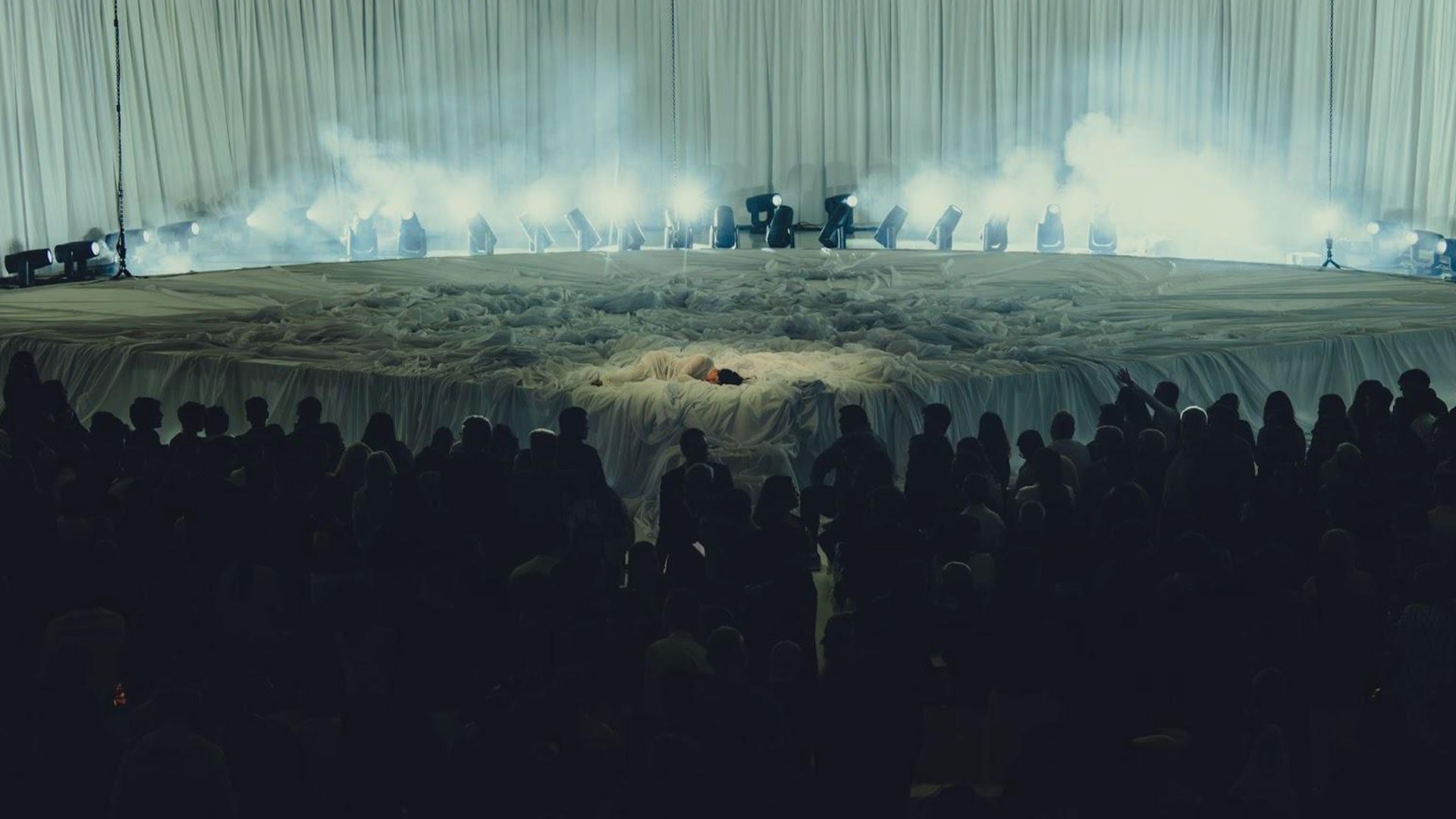

Critics love Lux, the fourth album from Spanish pop artist Rosalía. When the record was released this fall, The New York Times called her singing (in 13 languages!) an act of “practiced mastery,” and Pitchfork raved about the “operatic lament for a new generation, an exquisite oratorio for the messy heart.” As 2025 comes to a close, Lux is appearing on lots of best-of lists.

Lux is exciting, at times breathtaking and surprising. It’s also spiritual. It “harkens back to an older tradition of Christian art,” wrote The Atlantic’s music critic: “the symphony written for the glory of God.”

The album is filled with religious imagery, with allusions to female saints and sages across cultures and religions. “Berghain,” its first single, references Hildegard von Bingen’s experience of receiving a vision from heaven:

Die Flamme dringt in mein Gehirn ein

Wie ein Blei-Teddybär

Ich bewahre viele Dinge in meinem Herzen auf

Deshalb ist mein Herz so schwer

(The flame penetrates my brain.

Like a lead teddy bear

I keep many things in my heart.

That’s why my heart is so heavy.)

In Jeanne, Rosalía sings from the perspective of Joan of Arc on the eve of her martyrdom:

Je dis adieu

Je m’en remets

À mon Dieu

À ses vœux

(I say goodbye.

I entrust myself

To my God,

To his vows.)

She sings of non-Christian “saints” too: Buddhist nun Vimala, the Sufi mystic Rābiʿah al-ʿAdawīyah and Daoist master Sun Bu’er, as well as the Old Testament’s Miriam.

Religious imagery is nothing new for Rosalía. Crowned with stars on the cover of her second album, El Mal Querer, she looks very much like the Virgin Mary. Some of her song titles include the words liturgia (“liturgy”), lamento (“lament”), and éxtasis (“ecstasy”).

This time, though, the pop artist is making music on another plane. Like The Letters of Saint Catherine of Siena, Lux blurs, if not erases, the line between human and divine love. Often, the listener cannot be sure whether Rosalía is speaking to a lover or to God:

Sei l’uragano più bello

Che io abbia mai visto …

Fai tremare la terra

E si innalzi al tuo fianco

(You are the most beautiful hurricane

That I have ever seen. …

You make the earth tremble,

And it rises by your side.)

She sings these words in “Mio Cristo Piange Diamanti,” a song inspired by the friendship between Clare of Assisi and Francis of Assisi.

Rosalía’s dominating performance—when the album was released, she became the first artist to secure five No. 1 debuts across Billboard charts—is the latest in a recent series of high-brow artistic works to openly, even favorably, explore Christianity.

In 2019, Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag season 2 followed the titular character as she fell in love with a Catholic priest who, despite loving her back, chose God (and his vows of celibacy) over her. Two years later, Sally Rooney’s novel Beautiful World, Where Are You depicted two friends mourning the “misery and degradation” of late capitalism and finding something more than inspiration in the person of Jesus. “I am fascinated and touched by the ‘personality’ of Jesus,” writes Alice to her friend Eileen. “He seems to me to embody a kind of moral beauty, and my admiration for that beauty even makes me want to say that I ‘love’ him.”

Lux, too, is suffused with longing for God. In “La Yugular,” Rosalía chants,

Y un continente no cabe en Él

Pero Él cabe en mi pecho

Y mi pecho ocupa su amor

Y en su amor me quiero perder

(A continent can’t fit in Him,

But He fits in my chest,

And my chest occupies His love,

And in His love I want to lose myself.)

On “Sauvignon Blanc,” she seems to embody Matthew 6:21, expressing her desire to throw away earthly riches in order to attain God.

Perhaps these literary and musical shifts aren’t surprising. After all, religion is trending. The Pew Research Center reports that “Americans’ views about religion in public life are shifting” and a “growing share of the public takes a positive view of religion’s role in society.” Even in places known for their rampant secularism, like Silicon Valley, Christianity has seen a resurgence of interest, and church attendance is up.

Across the country, young people seem especially curious. Confidence in their government and economy is low as prices and temperatures rise. In unstable times, people search for a foundation, and Gen Z isn’t exempt. Many are returning to faith in God—or at least they want to talk about God. This is not the “spiritual but not religious” faith of the elder millennial. What we are seeing is a heightened interest in religion in its most ritualistic forms and, specifically, in the God of Christianity.

Yet although Rosalía believes in God, she is not a Christian. Lux, though worshipful at times,is not a worship album. Though Fleabag’s priest chooses Christ in the end, Fleabag herself does not. And Rooney’s Alice hesitates at Christianity’s call to repent and surrender, writing, “I have that resistance in me, that hard little kernel of something, which I fear would not let me prostrate myself before God even if I believed in him.” In all these works, young women yearn for connection with God (or at least with his ministers) and teeter on the verge of transformation. Ultimately, for one reason or another, they don’t take the plunge.

Perhaps there’s a correlation between these artistic depictions and recent surveys of young women showing that, although they score higher in “spirituality” and “attachment to God” than their male counterparts, they are nevertheless leaving the church in droves. Many of these young women cite sexism and dissonance between church teachings and their political views as their main reasons for leaving. Gen Z women are more likely to identify as pro-choice, queer, and nonbinary, making the issues of abortion and LGBTQ rights feel particularly personal.

Some of the dissonance these young women feel is no doubt the result of sinful behavior from Christians—ranging from discriminatory and hypocritical to downright evil. Some of this dissonance comes from the fact that the historic Christian sexual ethic and pro-life stance are no longer givens in Western society, stereotyped as needlessly judgmental and constraining.

Meanwhile, among Gen Z men, there’s been a surge in church attendance. For the first time in a long time, young men’s church attendance outstrips young women’s. The uptick has been reported by some Christian publications as a revival.

It is good that these young men are coming to church. It means that they, like Rosalía and the characters in Waller-Bridge’s and Rooney’s works, see something within Jesus that gives them hope. However, if reports showing a correlation between grievance culture, Christian nationalism, and Gen Z men’s renewed interest in church are true, then the revival is not uniformly encouraging.

If young men are converting to Christianity because of a desire to protect conservative, Western values, they are missing the point. So are the young women who express a keen interest in Jesus but balk at the restrictions of discipleship.

Both of these groups have some legitimate reasons for their mixed motivations toward Christianity. But true discipleship requires a willingness to surrender all our beliefs, desires, and identities to the “sharp compassion” of our “wounded surgeon”—that gentle, lowly, and altogether holy one we call Jesus. To every generation, he gives a call to death, in order that we may have life.

It’s still rare for young people to come to church, whether in buildings or in literature. What we must offer while they’re here is the call to discipleship. As Rosalía so poignantly sings in “Sauvignon Blanc,” “Mi luz / La prenderé / Con el Rolls-Royce / Que quemaré / Sé que mi paz / Yo me ganaré / Cuando no quede na’ / Nada que perder” (“My light, / I’ll turn it on / with the Rolls-Royce / that I’ll burn. / I know that my peace / I will earn / when there’s no— / nothing left to lose”).

Christina Gonzalez Ho is the cofounder of Estuaries. Joshua Bocanegra serves with that ministry, which is dedicated to discipling community leaders in a way that is rigorous, Spirit-filled, and holistically healthy.