Norman Rockwell’s 1943 oil painting, Freedom from Want, features a tableau of personalities around a dinner table. Their shoulders lean in, faces lit with anticipation, drawn in by what the matriarch of the family presents: the Thanksgiving turkey, the true main character of the scene. Who knows what conversation preceded the idyllic vignette—all the differing opinions on the hot button topics of the era—or which family members had conflicts with each other. In that moment, it mattered not. For the turkey had brought them together.

The turkey as a symbol of unity may sound familiar for those of us who eat forkfuls with mashed potatoes, dressing, and cranberry sauce. We may even have assigned to the bird a unifying, albeit somewhat fictitious narrative taught in elementary school, which paints friendly pilgrims and Native Americans gathering around the magnificent fowl.

The only species native to North America, wild turkeys can live in just about any habitat as long as there’s water and shelter. It’s truly an all-American bird, in a category with other great American unifiers like Lady Liberty and Uncle Sam. While it’s a myth that Benjamin Franklin lobbied to make the turkey the national bird, he did tell his daughter in a letter that he wished the turkey would have been chosen instead because it was “a much more respectable bird.”

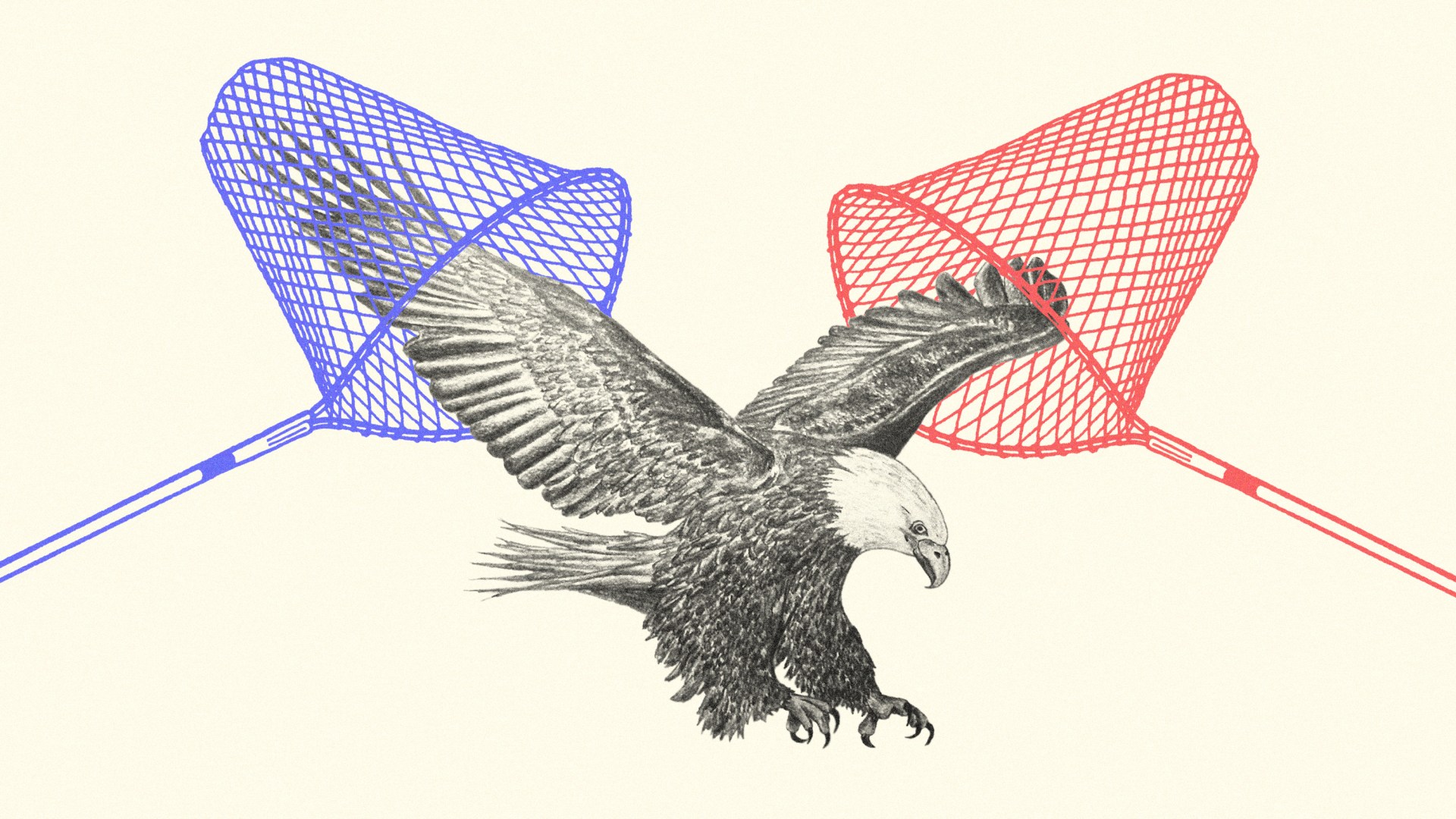

Today, researchers estimate there’s around 6 million wild turkeys across the United States. But despite its glowing reputation as a community centerpiece, this objectively weird-looking bird was once close to extinction. The survival of the wild turkey tells a powerful story of community and cooperation across differences. Every wild turkey that crosses the road—or arrives at the holiday table—represents the unified efforts of conservatives and liberals, biologists and hunters, and Christians and those outside the faith, reminding us that even in polarization, this great bird still creates unlikely friendships and brings people together.

“By the 1900s, subsistence and commercial market hunting had caused decline in the species,” says Roger Shields, wild turkey program coordinator for the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. Hunters noticed first. In response, a motley crew banded together, including hunters, biologists, conservationists, and lawmakers.

The result was the 1937 Pittman-Robertson Act, legislation that aimed to restore populations and conserve endangered species through an 11 percent tax on firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment. The act symbolized the beginning of the wild turkey’s advancement to mend cultural divides, says historian Brent Rogers, inviting stakeholders “outside of political norms because there’s blood, sweat, and tears invested into it, for hunters and biologists alike.”

While conservation efforts like President Roosevelt’s national parks initiative attempted to stave off threats to species like the wild turkey, at the turn of the century, habitat destruction caused by the industrial revolution prompted Aldo Leopold, a forest ranger in Arizona and New Mexico, to do more. He would one day inspire the likes of Wendell Berry and define a new conservation movement in the United States.

Jessica Moerman, chief executive of the Evangelical Environmental Network, says that Christians bring a unique understanding to conversations about conservation. By “stopping and preventing activities that are harmful,” says Moerman, we contribute to furthering “Christ’s reconciliation of all of creation to God.”

Moerman is a scientist but also the daughter of a turkey hunter, and she remembers the turkey calls in her father’s office when hunting season opened. “My dad always said hunters are the greatest conservationists,” she said.

Through the efforts of hunters, biologists, and conservationists, turkey populations increased by the mid-1900s. But the species remained at risk because of increased urbanization and decreased wild areas. Here, again, the wild turkey brought folks together. It turns out what’s good for the wild turkey is actually good for a host of other species too.

Efforts began countrywide to restore turkey habitats, and in 1973, the National Wild Turkey Federation was formally established. The work of the NWTF brought initiatives from each state into one coordinated, national effort inclusive of hunters, biologists, conservationists, and environmentalists to transplant healthy populations and preserve their environments. And it worked. By 1974, the wild turkeys numbered 1.4 million.

Michael Chamberlain, the National Wild Turkey Federation Distinguished Professor at the University of Georgia’s school of forestry, works in research and advocacy for turkey conservation efforts. “Those vegetative communities are largely beneficial for a number of critters, whether it be birds, pollinators, insects,” said Chamberlain. “Those species are going to thrive in the same plant communities that turkeys thrive in.”

Rogers, the historian, who is also a hunter, remembers seeing his first wild turkey in the 1980s, flying up out of the forested land his family had owned for decades. “Just watching it fly off, [I remember] thinking, That is a thing of grace and beauty.”

Today, Rogers uses all of the birds he hunts, even down to the feathers, which he sticks into his weathered Bible as bookmarks. (He even mailed me some, which now sit in the pages of my own Bible, marking my current reading spot in Acts.) He sees it as a reflection of God’s economy, where nothing is wasted. Raised Quaker in Iowa, Rogers has a feather resting on Psalm 8: “You put us in charge of everything you made, giving us authority over all things.”

“That is a privilege,” said Rogers after reading the passage over our Zoom call. “It’s also a burden. And as a hunter, you feel both.” For him, hunting carries a deep theological weight and responsibility that contributes to his particular hunting tradition. “I lay my hand on every turkey—even with people I’ve taken that are not spiritual people—and I say a prayer of thanks. Because to me, that’s a sacred act.”

Rogers and others like him believe that real hunters are also conservationists, because they know the cost firsthand. “A real hunter wants the animal to live more than you want it to die. And if you’re going to take, you have to give back.”

This is the paradoxical thesis of the hunter-conservationists who are at the core of this movement. The work of Rogers, Shields, and at one time, Leopold, has inspired what modern conservationists call a “land ethic.” Leopold articulated this ethic throughout his teaching career at the University of Wisconsin and in the 1949 seminal work published after his death, A Sand County Almanac. Almanac influenced people like Wendell Berry and leaders of the second wave environmental movement in the 1960s and 1970s, including those who noticed the wild turkeys were still in need of attention.

For all its triumphs, the wild turkey’s population restoration is also a cautionary tale. By the year 2000 there were turkeys everywhere, says Chamberlain. But it’s not that simple, because even while restoration was finding success, populations were already declining. It was Chamberlain’s Wild Turkey Lab that sounded the alarm in 2015. “We got lulled to sleep, which is just human nature,” he said.

Today, new environmental factors play a large role in the ever-evolving needs of the species. There are fewer wild areas, more threats with cars and chemical presence, and fewer large predators, which leads to more nesting predators who eat eggs. Rogers emphasized the urgency to continue conservation efforts from all who care about creation: “Unless we’re investing in research to teach us about new threats, we’re not doing our full job as stewards.” Restoration this side of paradise requires constant diligence.

When I asked Chamberlain what wild turkeys have taught him about community, he replied without hesitation, “Resiliency. You’ve got this bird that is so resilient but is yet vulnerable. The same goes for community. … Don’t take it for granted.”

Wild turkey conservation teaches us that there are corners of our American landscape where the sharing of literal common ground is the antidote to an anti-“us” era. Like the turkey itself, we are resilient yet vulnerable, interdependent in ways that need care to flourish. Our relationships with one another are susceptible to atrophy through complacency.

So while this Thanksgiving we may feel a unity around our own tables as fictional as a Rockwell painting, may we take heed of the very real call in Hebrews to show hospitality despite the many things that may put us at odds with one another. Maybe our eyes can fall on the centerpiece of the table—to the turkey itself—for a gentle and physical reminder of where the invitation in Romans to live at peace with others (12:18) has taken root and is still at work, shaping the very land on which we gather.