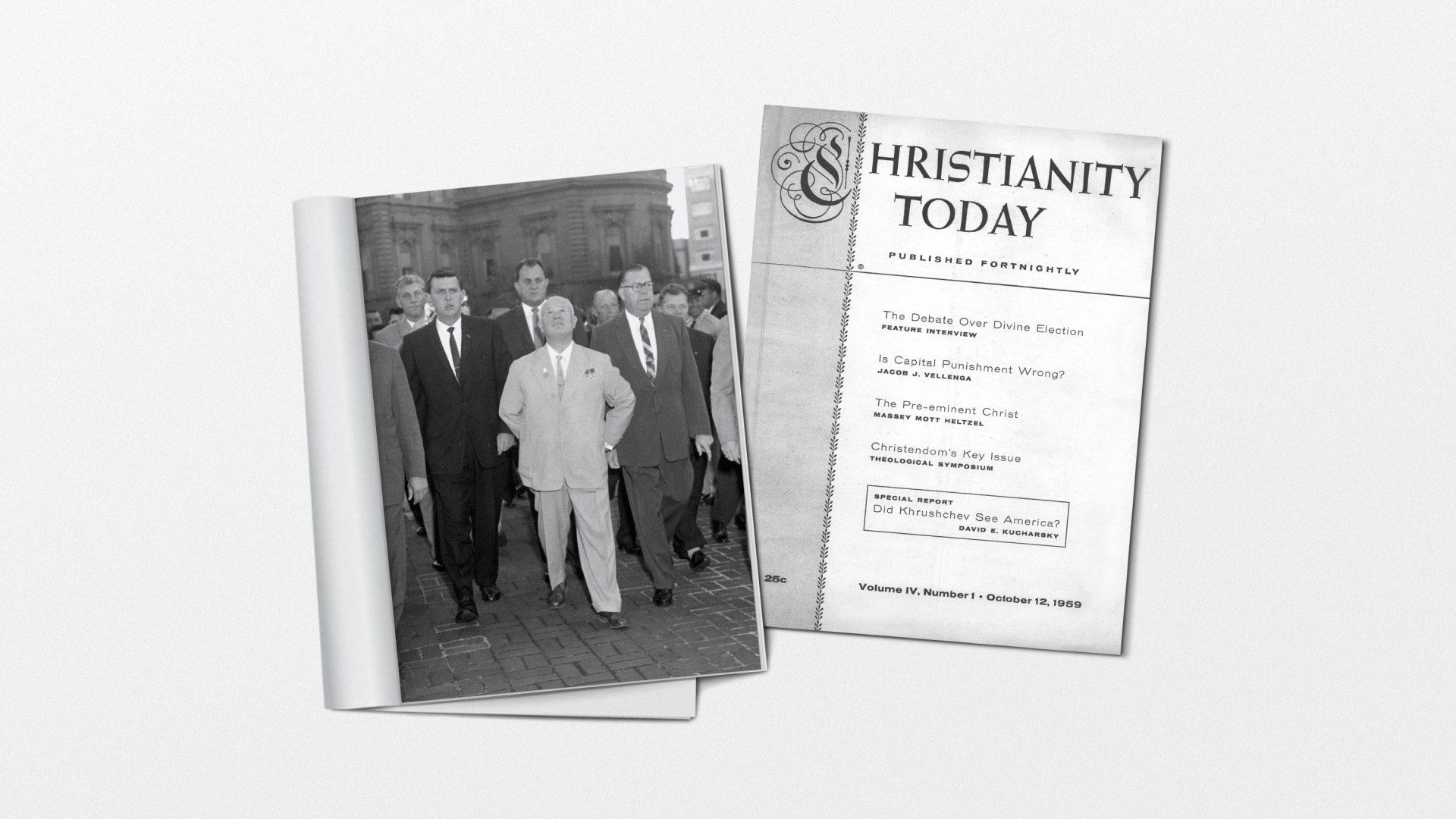

The great ideological conflict of the Cold War can feel abstract from the vantage point of history. In 1950s America, however, the threat of Communism loomed large. And Americans got the opportunity to hear directly from the world’s top Communist in 1959 when Soviet Union Prime Minister Nikita Khrushchev came to the US.

CT paid attention—and noticed one American leader who highlighted the spiritual deficit of Communist ideology.

Minutes after his silvery TU-114 appeared on the blue Maryland horizon, Khrushchev—one of the most celebrated international visitors since the Queen of Sheba—was reflecting his high priority for economics. …

“It is true that you are richer than we are at present,” the Red leader told a state dinner in the White House the same evening. “But then tomorrow we will be as rich as you are, and the day after tomorrow we will be even richer.”

The next 12 days bore out clearly what his first utterances hinted at: that Khrushchev was toeing the Marxist line which merges the dialectic with economic determinism as the comprehensive key to reality.

Preoccupation with economics characterized Khrushchev’s entire tour of the United States. …

Khrushchev viewed little during his stay that was distinctively Christian or that would underscore America’s great spiritual heritage. … It was left to Eisenhower to salvage something for the cause of Christian witness, and many clergymen feel his deeds on the final day of Khrushchev’s stay represented the most devout gesture during his entire term of office. Eisenhower not only broke into top-level talks with Khrushchev to attend a Sunday morning worship service, but invited the Red leader to accompany him. Khrushchev declined, explaining that an acceptance would shock the Russian people. But the impact of the President’s spiritual priorities was firmly registered.

Some Americans wanted to defuse the conflict with the Soviet Union, arguing that political leaders should go to great lengths to prevent the possibility of nuclear war. CT countered with a word of caution: Christians should understand that the biblical idea of peace is not the same as the vision that politicians promised.

The potentials of destruction in nuclear warfare are such that there is a crescendo of demand for some type of organization or machinery that will insure peace in our time.

But these appeals for peace on the part of political and ecclesiastical leaders involve considerations which few people are prepared to face.

Peace is not something that man can will for himself. It is a God-conferred blessing based upon obedience to God-ordained moral laws. Man cannot defy these laws and claim the blessings of peace. …

Part of man’s confusion today is due to his failure to understand what peace really means. The average person of the world desires peace only so he may continue, unharmed and uninterrupted, in serving the devil.

Our Lord made it plain that the peace of which he spoke had little in common with that concept of peace held by the world. He affirmed that he had come not to bring peace but a sword and that the peace he gives is foreign to, cannot be understood by, nor conferred at the behest of the world. And an understanding of this is possible only to those who are taught by the Holy Spirit.

People might feel like the advent of the atomic bomb, the Cold War, and the Space Race changed everything, but humanity’s spiritual needs are the same in every age. A Fuller Theological Seminary professor argued that was why evangelicals should not pursue peace at any price.

It is a fundamental of biblical anthropology that “there is no peace … to the wicked” (Isa. 48:22; 57:21).

It is utter folly to talk about the possibility of world peace when such lawlessness as we now see on this earth prevails. How can one talk of world peace when one third of the entire population of the globe has succumbed to the cruel, God-defying system of Marxian communism? … There is no more possibility for this earth to have peace when it wars against God, than it is for the human soul to have peace when it is at war with God.

The best way to respond to Communism became a fault line in American religion. CT reported on emerging divisions and potential Protestant realignment.

The National Council of Churches urged churches to study its recommendations of U. S. recognition and U. N. admission of Red China. Cleveland delegates could hardly have suspected that their proposals would lead, in some quarters, rather to a study of the NCC and the question of its value to the churches. Some church bodies have decided that they did not require a year’s study before making a pronouncement on the Red China issue. The American Baptist Convention, meeting June 4–9 in Des Moines, Iowa, was one of these.

Indeed, this lively issue provided the only extended debate of the sessions. After a number of staccato-like two-minute speeches, with delegates still wishing to speak, the convention voted narrowly, 245 to 234, in support of U. S. policy which denies diplomatic recognition to Red China and opposes its admission to the United Nations.

Evangelicals were also concerned about developments in contemporary capitalism, however. New research in marketing and advertising raised fear of subliminal messages and psychological manipulation. CT reminded readers that the gospel shouldn’t be packaged and sold like another product.

The use of guise and disguise in contemporary advertising is also provoking a long look at the religious use of persuasive techniques seeking the spiritual commitment of the masses. … In The Hidden Persuaders—a book now in its third or fourth printing, with built-in reader appeals of its own, and publisher’s advertisements alert to motivational devices—Vance Packard causticly indicts this “engineering of consent.” Packard touches the pulpit only in a passing way; neither the term “religion” nor “church” is found in his index. But what he says inevitably raises questions about the field of religious promotion. …

Without special lighting, microphones, and other electronic gadgets, many a pulpiteer today would feel quite cheated, and even lost. Perhaps, right there, is an occasion of stumbling. Do we perchance rely on gadgets more than on spiritual factors for effective proclamation? …

The work of the Holy Spirit remains the one indispensable factor in our effective presentation of the Gospel. The test of a “good commercial”—does it hurry a potential buyer to a sales transaction?—cannot therefore be pressed. Preaching is a hopeless pursuit apart from the life-giving power of the Divine Spirit. The outpouring and programming of the Spirit are entrusted neither to advertising agencies nor to church publicity clinics nor to ministers who have read Dale Carnegie. Christian virtues like love, joy, peace, gentleness, and faithfulness simply cannot be verbalized into Christian experience. Preaching reaches for genuine spiritual decision, and this cannot be engineered. …

The Gospel stands—once for all given to the saints. Only the package dare be changed, yet never by way of concealing the content.

Technological progress also raised new ethical issues. A Catholic statement condemning birth control occasioned reflection on the morality of contraception.

The declaration was only a logical extension of Catholicism’s well-known stand against use of contraceptives. But timed for release on Thanksgiving morning, the 1,516-word statement (formulated a week earlier at the 41st annual meeting of U. S. Catholic bishops) won headlines across the country.

Within hours birth control had become a major U. S. controversy which soon took a political turn. Senator John F. Kennedy, leading Catholic presidential aspirant, said he thought it would be a “mistake” for the United States to advocate birth control in under-developed countries. President Eisenhower said this would never happen while he is in office.

Reaction from Protestant quarters found a division of opinion on the morality of birth control itself.

Among evangelicals, the hullabaloo perhaps served to crystallize some convictions. Prodded by controversy, many went anew to the Bible for a re-examination of views on the legitimacy of sex severed from its procreative role.

Despite some sympathy for Catholic teaching on contraception, CT expressed concern about the church’s interest in political influence. Looking ahead to Democratic Sen. John F. Kennedy’s possible presidential campaign, a Methodist minister argued that Catholic involvement in America politics was changing quickly.

The penchant of the Roman Catholic for politics is well known. It extends both to laymen and clerics. The nexus of many a municipal political machine has been a close liaison between parish priest and diocesan bishop, on the one hand, and the boss, on the other. New York City, Boston, and Chicago offer ready examples. In New York City where 80 per cent of the Catholics regularly vote the Democratic ticket, no Protestant would have a chance to be mayor. …

On the national scene Roman Catholic political power is a formidable front unparalleled by organized Protestantism. The Catholic role has been that of king maker rather than king. While there has been an unwritten rule that the presidential nominee of the Democratic party must not be Catholic, there has been an equally prevailing rule that the chairman of the national committee must always be Catholic.

Now the Catholic genius for politics is taking a new direction. It turns from king-maker to king. It would like, perhaps, to achieve in the nation what it has already achieved in New York, Boston, and Chicago. It is challenging the prevailing rule (disastrously disregarded once) that no major party nominee can be of Roman Catholic faith. A groundswell within this communion advocates abandonment of the traditional taboo. This sentiment converges on Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, whose assets in seeking the Democratic nomination are his youthful charm and his father’s unlimited financial resources.

Turning to Protestantism, CT noted increasing debates about women’s ordination in 1959. The growing discussions seemed to skip important questions, though.

It is quite understandable that this question of feminine ordination to church offices should have arisen in our modern era. Feminism, or the modern theory of “women’s rights,” has impressed us so thoroughly with what women have been able to accomplish, that one is likely to feel boorish if he obstructs the modern advance. In fact, one feels that there is a kind of inevitability about opening offices to women. …

Few people have inquired whether feminine elders and ministers would not be something different from feminine doctors and lawyers. The assumption is that if women have achieved success and status in secular professions, why should they not have the same opportunities in the church? There is a curious reasoning process here that involves two fundamental fallacies: first, that everything included in the modern feminist movement is unquestionably good (“Give the little woman credit for anything she can get, man”), and second, that our modern day demands that we think like modern men. …

There is general agreement that churches ought to be governed in thought and practice by the teaching of the Word of God. This means that there must be no easy capitulation to modern ways of thinking simply because they are modern. Rather, we should endeavor to determine God’s will and way.

Editors also returned the critical question of Scripture and its inspiration.

The doctrine of inspiration continues to be in many ways the critical issue underlying all other issues in the Church today. A variety of statements vie with one another for assent. Labels are often attached to those who have no desire to follow any particular school. Judgments are passed in terms of traditional or less traditional alignments. Yet behind all other problems, concerns, or assessments, the primary question is still, as always, that of the biblical teaching itself. What are, in fact, the essential demands of the Bible with regard to its own inspiration? What are the basic factors without which no doctrine can claim to stand by the biblical and apostolic norm to which all attempted theological statements must be subject?