This is the second of a two-part series on Ismailism, a branch of Shiite Islam. To read part 1, click here.

An 11-acre Ismaili Muslim religious center is coming to Texas.

Part one of this two-part series described how the small sect of Shiite Islam will soon open the huge prayer hall and social center in Houston. Ismaili leaders emphasize an adherence to pluralism and interfaith dialogue, and this article will discuss how this assertion fits—or clashes—with Ismaili history.

For Ismailis today, who number between 12 and 15 million, pluralism is more than a commitment—it is near dogma. That is due to the center’s subsect, Nizari Ismailism, and its distinguishing feature: the living imam. Most Shiite Muslims name the leader of the Islamic community an imam, but only the Nizari sect claims he is alive and actively present in the world today.

And the imam’s legitimacy originates in his descend from Muhammad.

Islam’s prophet married and had several children, but only his daughter Fatimah survived to adulthood. She married Ali, Muhammad’s nephew and adopted son, and they had two daughters and three sons, one of whom likely died in infancy. All Muslims hold these descendants in high regard, and the current king of Jordan is one of thousands who trace their lineage back to Muhammad.

Yet the branches of Islam divided over who they saw as Muhammad’s true heir. Shiites believe that prior to his death, Muhammad designated Ali as his political and spiritual successor, so they call him “imam.” They also elevate Ali, Fatimah, and their sons Hasan and Hussein as Ahl al-Bayt, “the family of [Muhammad’s] household,” and believe these five received divine knowledge and infallibility. Only Muhammad holds the title of prophet, but his grandsons, in turn, became the second and third imams.

Sunni Muslims reject the claim of special favor, but honor Ali as the fourth community-chosen caliph, the highest Islamic political office. They dismiss the idea that an imam or any other human can inherit Muhammad’s aura of divine guidance.

Sunnis won the ensuing civil war in Islam and then set up a hereditary caliphate. Shiites rallied around Ahl al-Bayt, with some rebelling against the caliph’s authority and others adopting a quiet posture of perseverance. The majority, known as Twelvers, trace a line of 12 imams who from Hussein are designated directly from father to son. Twelvers are prominent in Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, and Azerbaijan.

Ismailis, found primarily in Central Asia, East Africa, and the Indian subcontinent, separated over a disputed succession. In AD 765, the Shiite community faced a crisis when Jafar al-Sadiq, the sixth imam, died at home, allegedly poisoned by the Sunni caliph who had previously detained him. Many of his followers believed he had designated his oldest son, Ismail, as the next imam—who died two years earlier than his father.

Sadiq’s other sons claimed Shiite leadership, with Twelvers following Musa al-Kazim as the seventh imam. But the crisis was more than just political—it was theological.

If an imam is infallible, how could he wrongly designate his successor? A dissenting party no longer in existence concluded that Ismail must still be alive and in hiding. Others held that Ismail’s son Muhammad should next inherit leadership, consistent with the father-to-son pattern. Most Ismailis today follow this line, and their head, known as Aga Khan V, is the 50th imam in the succession.

A century later, a different theological crisis hit the Twelver community. In AD 874, the eleventh imam died without an obvious heir. Consensus emerged that he did have a son who went into “occultation,” concealed from public view. Yet he never reappeared, and Twelvers judged that this Hidden Imam, miraculously preserved, will return to rule at the end of the age. Until then, fallible Shiite scholars lead the community.

In contrast, Ismailis offered Muslims a living imam, and their popularity surged as Twelvers fell into confusion over issues of leadership. As the inheritor of the leadership of Muhammad, Ali, and all proceeding figures in his line, the current Aga Khan—living today in Geneva, Switzerland—is believed by adherents to speak infallibly in spiritual matters and religious guidance. Similar to the pope in Catholicism, this infallibility does not carry over into his personal life or political choices. But when the time approaches, he will authoritatively designate his successor.

Today, the Aga Khan’s guidance is decidedly in favor of pluralism. But as with many religious traditions, Ismaili history is checkered. As a minority religious group, at times Ismailis have felt compelled to hide their faith. At other times they fought fiercely for political power. And in the 9th century their numeric growth helped establish a caliphate of their own.

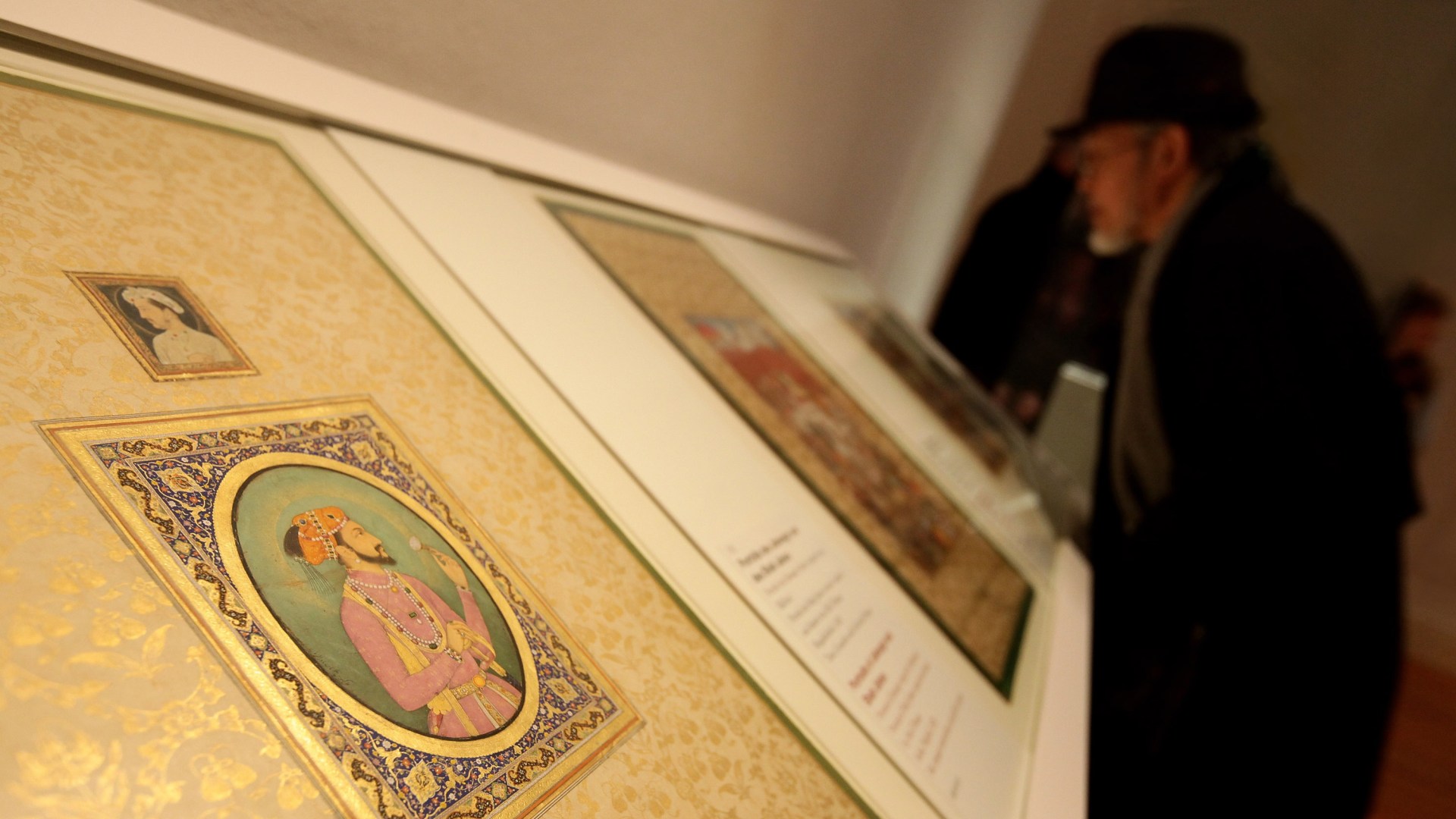

During their two-century rule from Cairo, the Ismaili Fatimid empire treated Coptic Christians relatively well, governing a diverse population that included a Sunni majority. While Ismailis taught their faith and established the renowned Al-Azhar University as an Ismaili center, they did not impose their doctrines on the population.

One imam, however, reversed this toleration. Al-Hakim required Jews and Christians to wear distinctive clothing, banned the celebration of Easter, and destroyed several churches. His policies appeared to follow political convenience, as he later lessened the persecution and turned against his fellow Shiite rivals.

These rivalries continued. When a later Fatimid imam died in AD 1094, his powerful adviser favored the younger son al-Mustali over firstborn Nizar. The majority branch of Ismailis today believe Nizar was the designated imam, yet he was killed in his subsequent revolt. A minority, primarily in India, believes a descendent of al-Mustali, hidden from public view, remains the rightful Muslim ruler.

The Mustali Ismailis maintained their rule over Fatimid Cairo and expelled from Egypt a Nizari missionary who continued spreading the faith. Hasan Sabbah eventually returned to his native Iran and secured control of a mountain fortress, from which he established another political entity and the Order of Assassins, which killed dozens of high-profile political leaders. Legends carried to Europe by returning crusaders spoke of an elite unit of drug-crazed yet professional hitmen, trained in majestic gardens and surrounded by harems of beautiful women.

Explorer Marco Polo told stories of the medieval Hashishin. The English word assassin is derived from the Arabic word for the narcotic hashish, but modern scholarship refutes the legitimacy of this connection, as there is no evidence of drug use by the order.

History does chronicle the assassins’ murder of two Muslim caliphs and the crusader king designate of Jerusalem, alongside numerous other Islamic and Christian leaders. Ismaili sources cast doubt on their responsibility for some of these assassinations, describing instead a policy of self-defense from within scattered mountain fortresses.

For centuries, Ismailis say, Sunni authorities harshly persecuted them. They skinned Ismaili leaders alive, threw them into bonfires, and crucified them on city walls. And when the Mongols ransacked Muslim territories in the 13th century, some estimates place Ismaili deaths at more than 100,000. A Sunni historian said “no trace was left” of their community.

Ismailis ensured their survival through a policy of taqiyya—an Arabic word meaning “dissimulation,” the hiding of one’s true beliefs under duress. Early leaders pretended to be merchants as they directed a missionary campaign in Sunni-led Syria. Another leader escaped the Mongols by disguising himself as an embroiderer. Later, Ismaili adherents posed as Sunnis, members of other Shiite sects, or even Hindus to blend in locally.

Some Christians cite taqiyya as a reason not to trust Muslims, calling it permission to lie. Other Christians dismiss this claim as false, as do Shiite leaders. But some Ismailis have used deception as a tactic. The founder of their ministate in northern Iran first gained access to the fortress by pretending to be a schoolteacher and then converting the garrison forces. During the Crusades some Ismailis switched sides between Christian lords and Sunni caliphs. And to kill one leading Sunni adviser, an assassin presented himself as a Muslim mystic.

While fleeing Mongol persecution, one Ismaili imam, Shams al-Din Muhammad, reportedly said that taqiyya is “my religion and the religion of my ancestors.” The early imams relied on the practice, Shiites say, to protect the line of the prophet from one generation to the next against Sunni authorities who allegedly poisoned Shiite leaders. Other imams outwardly cooperated with the caliphs while hiding their inner conviction of leadership, hoping to secure greater freedom for their community. Because Shiites saw the imam’s example as infallible, they took up the practice of taqiyya as a community resource.

Ismailis only reemerged as a distinct community in the 19th century when the Shiite Qajar state in Iran appointed the first Aga Khan as a regional governor. After a failed rebellion, he fled to Afghanistan, befriended the British, and settled in India. There the Ismaili imam won a legal case to be the exclusive religious representative of the wealthy Khoja merchant community. Under colonial rule the Aga Khan became a cofounder of the All-India Muslim League and gained global prominence as an Islamic spokesman.

Modern Aga Khans went on to call for inter-Muslim unity worldwide. This is a model for today, Ismailis say, for much blood has been shed between the sects, then and now. Aga Khans also pursued international consensus, and Muhammad Shah, the third in the modern Ismaili line of leadership, became president of the post–World War I League of Nations.

“The tribulations of one people are the tribulations of all,” stated Aga Khan III to the assembly in 1937. “This is no empty ideal. It is a veritable compass to guide aright the efforts of statesmen in every country and of all men of good will who, desiring the good of their own people, desire the good of the whole world.”

At his accession speech as Aga Khan V last February, Prince Rahim, the 50th Nizari Ismaili imam extended a similar vision of tolerance for all humanity. He committed to continuing the work of the Aga Khan Development Network, whose interfaith work was described in part one of this series. As his worldwide community pledged their allegiance to his leadership, he urged them to be loyal and active citizens of the countries in which they live.

Correction: An earlier version of the story misstated the city where Aga Khan V lives and the name of the Aga Khan Development Network.