The former pastor of one of the biggest churches in Texas has pleaded guilty to child sex abuse that took place over 30 years ago.

Robert Morris, the founder of Gateway Church on the outskirts of Dallas, will serve six months in an Oklahoma jail under a ten-year suspended sentence and register as a sex offender. Under the plea deal, Morris will also pay the survivor, Cindy Clemishire, $270,000, according to The Dallas Morning News.

Morris is among the highest-profile pastors to face a legal sentence for child sexual abuse, since decades-old cases rarely result in criminal convictions or guilty pleas.

Morris, 64, pleaded guilty to all five counts in the case, charges of lewd or indecent acts with a child. Law enforcement officers cuffed him and led him out of the Oklahoma courthouse where he was sentenced.

The crimes took place in the 1980s and came to light in June last year when Clemishire publicly disclosed that Morris had abused her as a 12-year-old.

The molestation took place over four years, Clemishire told the abuse watchdog blog Wartburg Watch, and took place at her family home in Hominy, Oklahoma, where Morris would stay as a traveling pastor. She said Morris would come into her room and touch her under her clothes, with the molestation eventually escalating to attempted intercourse. Morris was married and in his 20s at the time.

Morris resigned from Gateway following Clemishire’s disclosure last year, and after an independent investigation, the church removed four elders for knowing his abuse involved a minor.

Gateway elders initially said they believed the “extramarital relationship” was with a “young lady” and not a 12-year-old, and they said Morris had already undergone restoration. The church later apologized for that characterization. A law firm hired by the church for an independent investigation did not find additional victims.

At the court hearing, Clemishire told Morris directly that she was “not a young lady, but a child. You committed a crime against me.” NBC News reported from the courtroom that Clemishire’s 82-year-old father was crying.

One of Morris’s attorneys told the Associated Press that Morris pleaded guilty to bring the legal matter to an end for the sake of him and his family and Clemishire and her family.

“While he believes that he long since accepted responsibility in the eyes of God and that Gateway Church was a manifestation of that acceptance, he readily accepted responsibility in the eyes of the law,” said Bill Mateja.

Clemishire continued in her victim impact statement in court, “Today is a new beginning for me, my family, and friends who have been by my side through this horrendous journey. I leave this courtroom today not as a victim, but a survivor.”

She added that she hoped that her story would help other victims, to “lift their shame and allow them to speak up. I hope that laws continue to change and new ones are written so children and victims’ rights are better protected.”

Criminal convictions for child sexual abuse are unusual to begin with. The mean age for victims abused as minors to disclose abuse is in their 40s or 50s. When victims typically come forward with their stories decades later, civil penalties might be the only remedy available to them due to statutes of limitation.

Oklahoma attorney general Gentner Drummond said when an Oklahoma grand jury indicted Morris in March last year that the statute of limitations did not apply to Morris because he was never a resident of Oklahoma. The state’s legal system established during the frontier era was meant to deter people from committing a crime and fleeing the state, he said.

“This case is all the more despicable because the perpetrator was a pastor who exploited his position of trust and authority,” Drummond said in a statement on Thursday. “The victim in this case has waited far too many years for this day.”

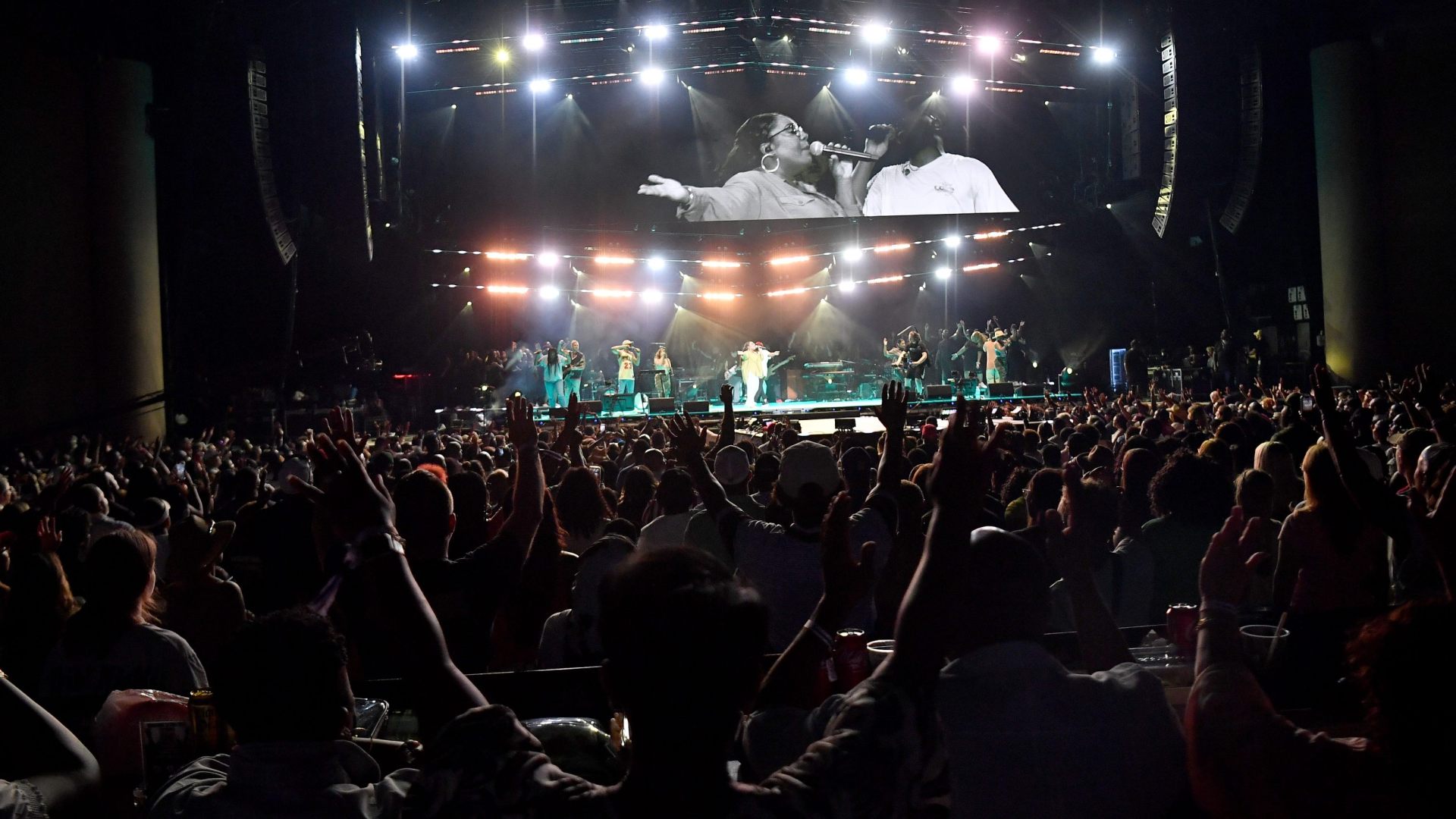

Morris founded Gateway Church in 2000. It grew to tens of thousands of congregants at multiple campuses in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Gateway produced famous worship leaders like Kari Jobe, and Morris was a spiritual advisor to President Donald Trump in his first term.

Since Clemishire’s disclosure, Gateway congregants have also filed a lawsuit against Morris and Gateway, alleging the fraudulent use of their tithes. A federal judge recently ruled that that suit can proceed. Clemishire is also pursuing a civil case against the church.

In the months after Morris’s resignation, attendance at Gateway dropped precipitously. That summer in Dallas-area churches a number of megachurch leaders resigned over sexual misconduct.

This is a breaking news story and will be updated.