In this series

After enrolling at Delta Streets Academy (DSA) in Mississippi in 2016, Imanol Moreno said, he “slacked a lot.” As a middle schooler who pushed back against the rules, Moreno often had to stay after class to handwrite pages crammed with sentences like “I want a disciplined education.” Fed up, he told his parents, “I don’t want to go there no more.”

His father told him to stick it out. The next year, Moreno decided to follow Christ, encouraged by his religion teacher, Nick Carroll. “I started doing my homework, got closer to Christ, put my britches on,” Moreno said.

He graduated from DSA in 2021 and earned an associate’s degree in business management in 2023. He works as the office manager and heavy equipment operator at the construction business he and his father started. “I still read the Bible they gave me at Delta Streets,” he said. Moreno credits the school with sparking his love for math and teaching him to learn from his mistakes. “My life wouldn’t be what it is now without Delta Streets.”

Not every story from DSA ends up like Moreno’s. The Christian academy for low-income boys faces a high attrition rate and distrust bred by decades of segregation in the South. But its leaders keep pushing forward, offering challenging academics and Christian hope to nearly 100 Black and Hispanic boys in grades 4 through 12.

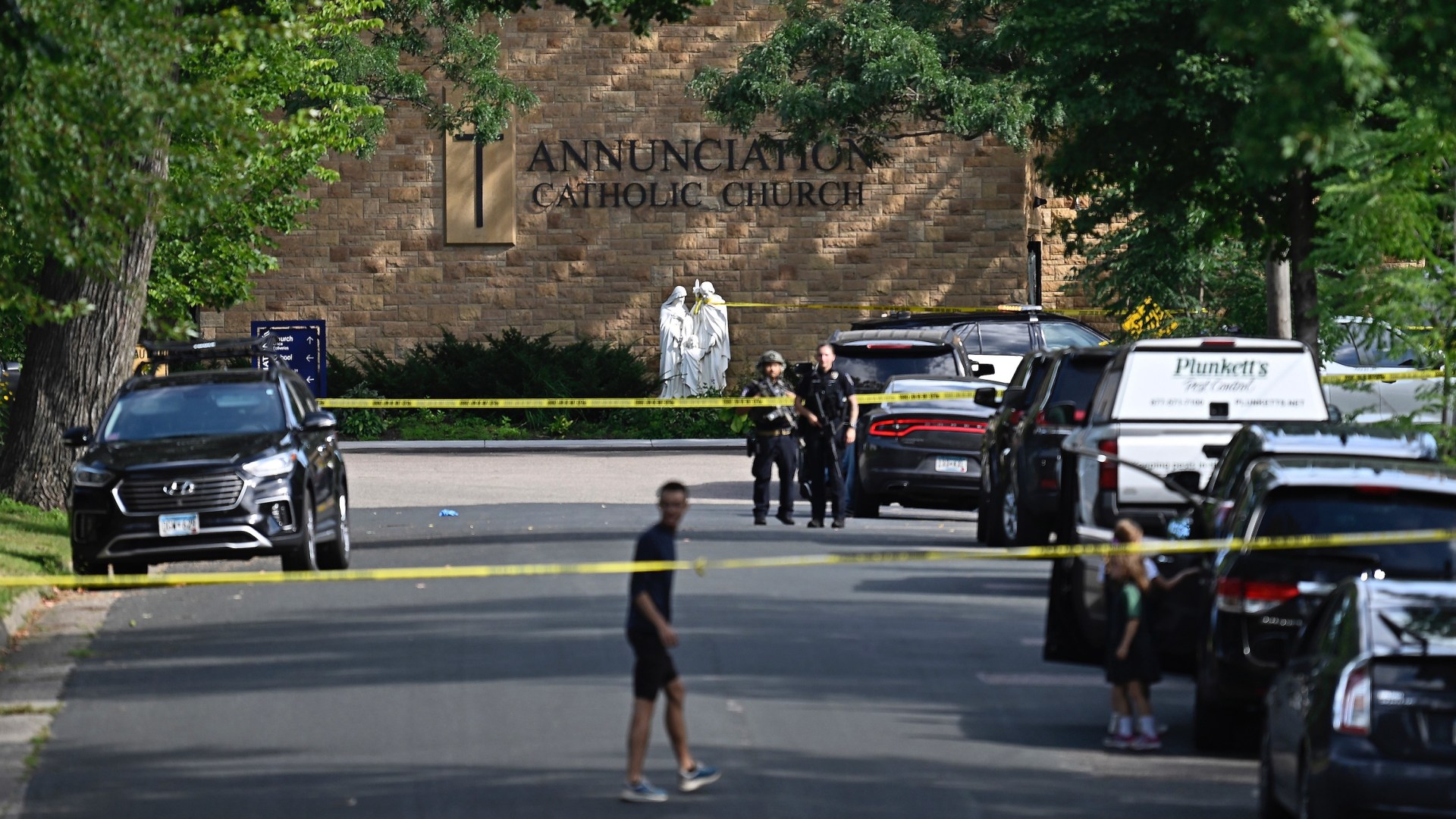

The school is situated two blocks from Greenwood’s gutted downtown, where mom-and-pop shops alternate with swaths of broken, boarded-up, or empty windows.

Photography by Timothy Ivy for Christianity Today

Photography by Timothy Ivy for Christianity TodayThomas “T. Mac” Howard, who founded DSA in 2012 after teaching math at a poorly rated local high school, talked about his philosophy for the school while elementary-grade boys played soccer in their new gym. The kids run around for an hour before their first class, in addition to recess after lunch. “The more energy they can burn, the better [they can] focus on class,” Howard said.

Many students arrive at DSA reading well below grade level after spending time at low-performing public schools. Nearly one-fourth of the boys who stay in the local public schools drop out, and the ACT scores of those who stay at the high school are around 20 percent below the national average.

But for $75 a month, low-income families can send their sons to DSA, which is housed in three steel-clad buildings across the street from a pawn shop covered in ivy and a rundown house nearly concealed by a porch of old furniture.

DSA’s mark system is part of a highly structured disciplinary plan. Students receive demerits for failing to turn in homework, speaking out of turn during class, and more. Two marks, and they’re stuck eating “silent lunch” away from their friends. More, and they must stay after school to write one page per mark.

The strictness doesn’t keep classrooms from coming alive, though. In fourth-grade English, hands shot up to answer Kristen Montgomery’s rapid-fire questions about verbs and adverbs. Beneath a tall brick wall painted with the word “CADILLAC”—left over from this building’s past life as a dealership—some of the boys fidgeted or lip-trilled, but they paid attention.

In fifth-grade social science, students shouted replies to Edna Williams’s booming questions about the tortoise and the hare. In tenth-grade English, nine students discussed a novel, connecting the teenage characters’ experiences to their own. During lunch, the cafeteria buzzed with conversation (probably boosted by a strict no-phones policy).

Class sizes at DSA are small, with just 15 fourth graders enrolled last fall and about 9 students per graduating class. Mississippi Delta parents are not beating on the DSA doors for their children to get in. Howard says, “The verdict of the Black community is still out on Delta Streets.”

Downtown, a statue of Emmett Till stands just 36 miles from the courthouse where an all-white jury acquitted the Black teen’s white murderers in 1955. Segregation died on paper in 1964 but isn’t yet buried. Milton Glass, pastor of the New Green Grove Church of Faith, told CT of a common “stigma”—which he repudiates—that “private school is for white people.”

Photography by Timothy Ivy for Christianity Today

Photography by Timothy Ivy for Christianity TodayWhites fleeing desegregation started many private schools in Mississippi, and most white students in Greenwood go to one. Greenwood High’s student body is 95 percent Black, and most of the teachers there are Black too. Howard is white, as are most DSA teachers. Howard acknowledges that DSA struggles to recruit and retain Black teachers; public schools can offer higher salaries.

Coretta Green, a Black teacher set to become the school’s first elementary principal this fall, has learned that it’s important to provide immediate incentives for students. Kids “fight harder” when rewards are on the line, she said. She started buying goodie bags for students herself. Now, she has added awards for perfect weekly attendance, student of the month, fewest marks, and honor roll.

Green appreciates working for a Christ-centered school with morning devotions—and the student body comes with another bonus: “No girl drama.” But that also keeps some boys away, as do the limited opportunities for athletic recognition. (DSA’s small teams struggle to compete against bigger schools.)

Another barrier to entry is the tuition. For some families, even $75 a month may be unaffordable. “If it was free,” Glass said, “you would have a whole lot more.”

Ty Korsmo is a journalist based in Houston, Texas.