Founded 75 years ago, World Vision has grown into the largest evangelical humanitarian organization in the world. World Vision’s US office, the largest of its many global affiliates, is also one of the top recipients of US foreign aid grants.

This year, the Trump administration froze or canceled most projects overseen by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the now-shuttered humanitarian arm of the federal government. In March, as Christian humanitarian groups met with State Department officials to try to save some programs, leaders from World Vision said the charity might need to lay off as many as 3,000 employees due to the funding cuts.

While other faith-based aid groups have spoken out publicly, World Vision has remained mostly quiet. The foreign aid shutdown came just after World Vision launched an ambitious new goal of reaching 300 million people worldwide through its sponsorship, water, health, and food programs.

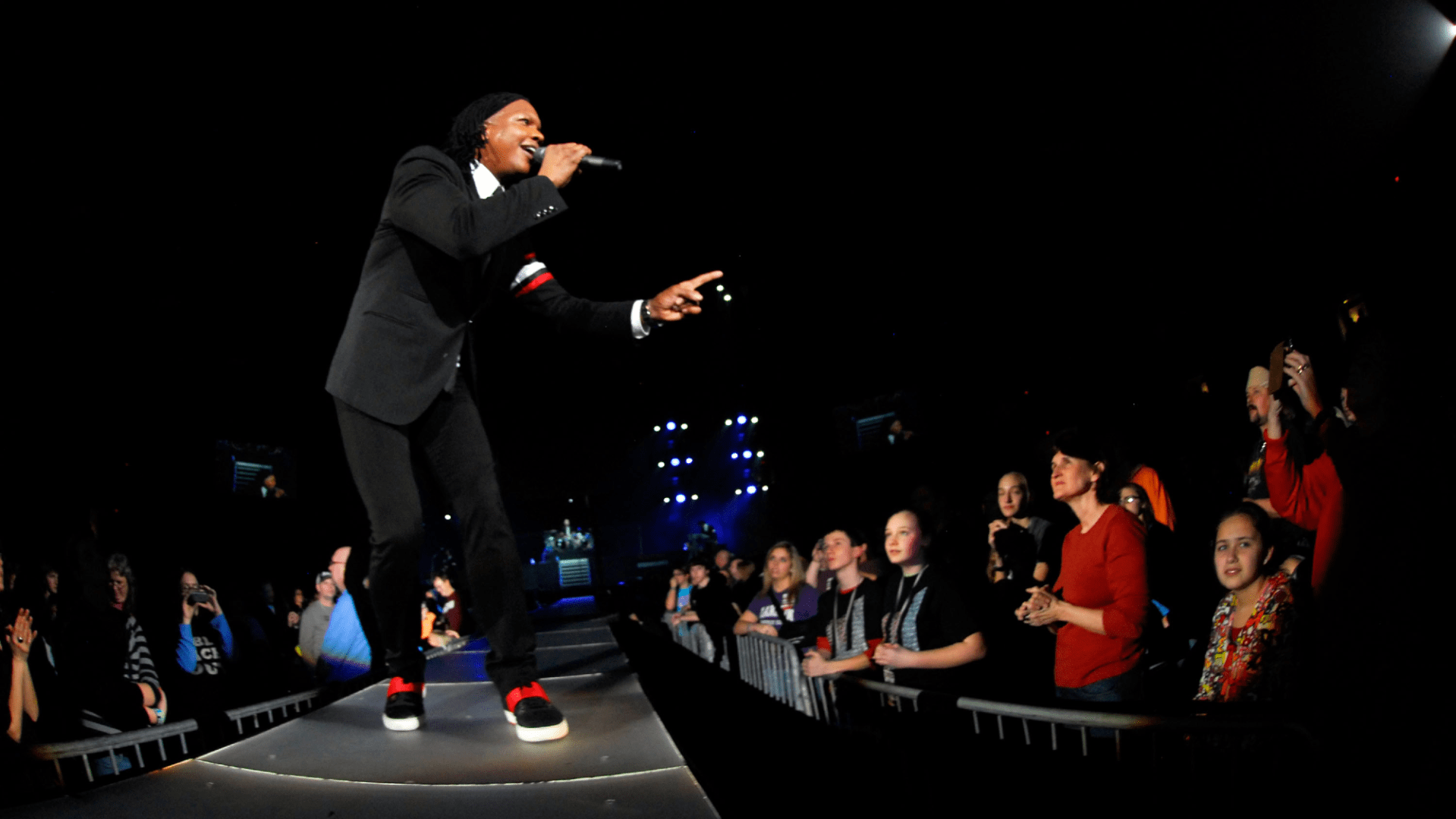

In early July, CEO Edgar Sandoval spoke with Andy Olsen, CT’s senior features writer, about World Vision’s staffing cuts and the role of government funding in faith-based aid. The conversation is below, edited for length and clarity.

We are talking a few days after the official closure of USAID. Over the last few years, World Vision has received more than $400 million a year in foreign aid grants—including cash and noncash items like food commodities. That’s roughly a third of your annual revenue. How have government funding cuts and pauses affected your budget?

Even before the USAID cuts, there was already a significant gap in funding. There were more humanitarian needs than available funding. And now with these cuts, depending on what happens next year, it only makes a challenging situation even more challenging.

We have a very diversified portfolio of funding, as you know, and the vast majority is private donations. But the US government is an important part of our portfolio. In 2025 we’re looking at losing about $170 million, which amounts to about 10 percent of our total budget.

Before we heard about the stop-work orders, we had already heard about a desire to review foreign aid. I welcome that wholeheartedly. We should always be looking at getting more efficient and better at what we do. I spent 25 years of my life, before coming to this Christian ministry, in corporate America. We were constantly looking at inefficiencies and getting rid of them. Any well-functioning body has some level of inefficiency.

Now, a lot of this funding is truly lifesaving funding for people who live in the most unimaginably challenging environments and conditions. There are no local markets. There are no infrastructures. These people need a safety net to help them build a life and a livelihood. So when we received stop-work orders, we immediately got to work looking for waivers for some of our programs that were lifesaving. Even though it was challenging and a bit confusing at times, we were able to restore many of the grants that were stopped temporarily.

Can you help me understand how World Vision’s programs break down between privately funded work and government-funded work? Are those funding streams and the programs they support entirely separate? Or are they intertwined in such a way that the impacts of cuts are felt across the organization?

Yes and yes. Our flagship program is our child-sponsorship program. And that is very strong and continues to get stronger over recent years. We also layer other private funding in the communities where we’re doing child sponsorship, to accelerate the impact. What we do with US grants is extend our reach at a massive scale. In some instances, the grants are in the communities where we work with sponsorship, but in many instances they’re not—particularly for humanitarian crises and natural disasters.

What makes these cuts very challenging is that we’re not talking about, call it, one-off programs, like installing a water well or a clinic. We’re talking about massive programs at scale. We’re talking about lifesaving food assistance to 500,000 people, vaccinations to 400,000 people, every month monitoring entire regions for diseases and disease prevention. Replacing that funding doesn’t happen overnight. The vast majority of our funding is donor designated, meaning it was donated for a particular purpose in a particular place for a particular time period. And we honor donor promises. We can’t just unplug and do something else to cover the gap.

Are there programs that World Vision has outright had to cut? Are there communities in the world that last year were receiving support from a World Vision program and now are not?

Yes, absolutely. I’ll give you an example. I was in Ethiopia a week and a half ago. What I saw was both encouraging and devastating. I visited one of our warehouses where we store food. This is food that’s been sourced from American farmers—sorghum, peas, et cetera. We were doing one of the last food distributions for that area. It’s an area that’s been going through a very challenging drought. I saw the crops dying because there’s no rain, and this is supposed to be the rainy season. People are working hard, but the rain doesn’t come, and they can’t feed their children.

When I walked into the community for our food distribution, the community just broke out in a big applause. What struck me at the time is, first, they probably didn’t know that the program was coming to an end. But second, they were clapping for America. They know this is from America. They told me, We’re so grateful for America. America has a good heart. Americans are generous. Please tell Americans how much we appreciate them and that they are helping us save our children’s lives.

There is a chance that we may restart in January if we get a reinstatement on the grant. But as of right now, we’re planning to shut it down.

Speaking of food aid, I was reading a statement that Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued on July 1, officially announcing the closure of USAID. He wrote, “Where there was once a rainbow of unidentifiable logos on lifesaving aid, there will now be one recognizable symbol: the American flag. Recipients deserve to know the assistance provided to them is not a handout from an unknown NGO, but an investment from the American people.”

Anyone who’s worked in foreign aid is accustomed to seeing bags of rice or whatnot that are stamped with the American flag and the motto “from the American people.” Do you see evidence to support the critique that aid recipients somehow don’t understand where the aid’s coming from?

The flag is there on every bag. And “from the American people.” I feel proud to represent America when I go out there and see the help that the US government is bringing to these families.

We just want to help people thrive. We think foreign aid—when properly administered like we do through World Vision and many other organizations—it saves lives. It saves lives here in America. It saves lives across the world. It creates resilient communities. It eradicates disease completely, and it creates goodwill. And all of that I think leads to a safer, stronger, more prosperous USA. Whether I put World Vision’s logo or not is not the key priority for us.

Jon Warren / World Vision

Jon Warren / World VisionThe administration has said that foreign aid needs to advance the nation’s interests, that a key objective of foreign aid is to encourage global political and ideological alignment with the current administration. I don’t think that’s an entirely new way for American presidents to approach aid. I’m curious how a Christian organization like World Vision navigates those kinds of expectations while also managing the more straightforward humanitarian and faith objectives of its programs.

We are a Christian ministry motivated by our faith, following what we believe are God’s wishes for every follower of Jesus Christ, which is to help the poor and the oppressed. We appeal to many different sources of funding. The vast majority are Christian private donors. But we believe God has blessed World Vision with the capabilities to do things at a scale that not many organizations can, Christian or secular. If we can be viewed as a partner of choice to the US government to accomplish that work, to help people lift themselves out of extreme poverty, to live through food emergencies, to have vaccinations so that the children don’t die, we’ll do that.

Once the administration and Congress decide what they’re going to fund, we are just focused on maintaining our status as a partner of choice to implement and to implement with excellence. For instance, World Vision is the number one nonprofit provider of clean water in the world. We’re the number one distributor of the World Food Program. In fact, we distribute more American farming commodities around the world than anybody else. And so that’s what we’re focused on. As part of the knowledge that we’ve gained over the years, we’re advocating for ‘Hey, keep some key programs that the government funds.’

An important point here that I’d like to make is this: Foreign aid is less than 1 percent of the federal budget. The American people know that foreign aid is good. In fact, the vast majority overwhelmingly support keeping the 1 percent. The issue is that most Americans believe that the foreign aid budget is somewhere between 10 and 20 percent of the total budget. But when you actually explain and they understand that it’s 1 percent or less, they overwhelmingly support it.

But to be clear, World Vision staff are not submitting reports to the government outlining how your programs are serving US interests. This is not a thing?

I’m not aware of submitting any reports of that nature. We agree with the government on objectives, on the type of outcomes that we’d like to see, and then we measure those, and we measure those with a lot of discipline and with a lot of work. That’s the only way we’ve been able to earn and maintain our preferred status, not only with the government but with most of our private donors. We do reports for them all the time to make sure that their investment is achieving what we said it would.

That said, I would be very quick to say that all of these things, again, they do help America. For instance, let’s just take the emergency food that I mentioned. That infrastructure supports an estimated 60,000 jobs right here in the US, when you consider the entire supply chain, from the farmers to the trucks that transport farm commodities to the ports.

Can we talk a little bit about layoffs? What the impact has been?

The decision to let go of staff is one of the hardest decisions a leader can make. We don’t make those lightly. It was challenging to have to say goodbye to about 11 percent of our staff here in the US, which is proportional to the 10 percent cuts that we saw. It’s particularly challenging in a ministry like ours where people have been called to do this work.

On the field-staff side, because it’s directly funded by grants, there have been stops and starts as we have reinstated grants. Initially we thought there would be maybe 2,000 or so people that we would have to let go. The actual number has turned out be a lot less. I don’t think we’ve let go even 900 so far, because many other programs were reinstated. But if they go away completely, then we may have to do some more things, particularly on the field side.

I’d like to talk about public perception. As you are well aware, Elon Musk called USAID “a criminal organization” and “one of the biggest sources of fraud in the world.” Secretary Rubio said executives at aid organizations “enjoyed five-star lifestyles funded by American taxpayers, while those they purported to help fell further behind.” The leaders that he’s talking about are people like you. How do you wrestle with that?

Well, I’m not sure they’re talking about me. I can only comment about what I’ve seen in all of my travels to all of the countries. I have seen fully committed Americans who’ve given their entire professional lives to serve their country. They are doing really good work.

Both the statistics and the stories bear that out. Let’s look at what’s happened with foreign aid and with America’s leadership in foreign aid over the years, over the decades. We’ve had 26 million people who are alive today because of PEPFAR, the signature American program against HIV and AIDS. We have 7.8 million children who were born HIV free as a result of that program. The world has eradicated smallpox. We’ve had, I think, more than a 95 percent reduction in polio. Malaria in Africa has been cut by 50 percent. Child mortality has been cut by out whopping 59 percent.

I just came back from Ethiopia, as I mentioned. I spoke to a community leader. This strong man, he broke down and started to tear up as he played back to me the possibility that the food would stop coming to his community. He was very grateful to Americans. He said, “If and when the food leaves, death will come into my community.”

Are we in a moment when World Vision has to sell itself or resell itself to Christians who have grown skeptical of faith-based aid in recent years?

We’re always telling our story and telling the story of what God is doing through World Vision. I don’t know that that’s necessarily “selling” World Vision or “selling” aid to the most vulnerable. I think Americans have incredibly generous hearts. They are very generous. We’re just all bombarded with so many priorities and with so many things, and it is our role to remind people of what God expects of every Christ follower. There are over 2,000 scriptural references to helping the poor and the oppressed. I mean, it couldn’t be more clear.

Have you met recently with members of the administration or senior leaders at the State Department?

We have a lot of engagement with the Hill, with our administrators. I was there back when the cuts began, and I travel regularly also to meet with them. What I would say is that there’s still a level of uncertainty, but I remain hopeful. I believe that our leaders want to do the right thing. They understand lifesaving aid is important, and it is my hope that they will see organizations like World Vision as one of those that they can count on to deliver on their objectives.

How often do you get to the field?

Three times a year or so.

Do you have a favorite place?

Every time I visit a country, it becomes my favorite. I’m just so inspired by the work that our staff does. They’re so committed. They put themselves in the hardest places. They serve their communities. Eighty percent of our staff live in the communities where we serve, and many of them do so at a great personal cost. They leave their families in other cities for months at a time. And when I ask them, “Why do you do this?” it doesn’t matter whether I’m in Africa, Latin America, Asia. Wherever I am, the answer is the same: “Our calling from God to serve our people.”