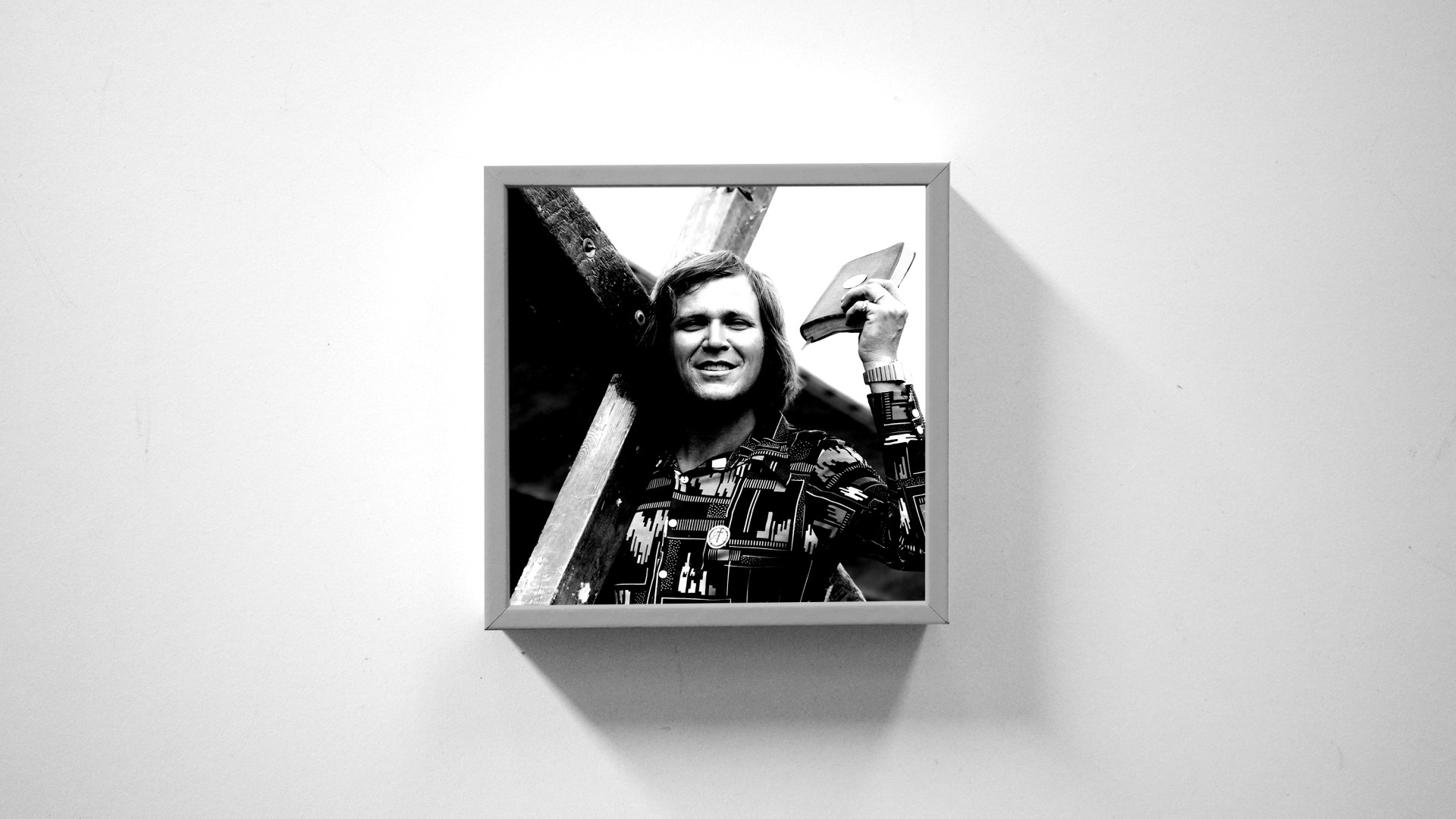

People had a lot of questions when they saw a hippie minister with slightly shaggy hair hauling a 12-foot cross with a wheel across North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa, hauling it down highways, up mountains, into deserts and jungles, through war zones, through cities and remote villages, and into countries where he did not know the language or understand the customs.

They asked what he was doing. Where he was going. And most of all, why.

Arthur Blessitt would answer with the gospel. He would say, “Jesus, man, he loves you,” and tell them the cross was a sign of how much. He would say, “If you would like to know Jesus and invite him into your heart, please pray this prayer with me now, Dear God, I need you …”

Blessitt did that for 43,340 miles, by his count. Which worked out to about 86 million steps and shoes he had to resole or replace several times every year.

He started in Hollywood in an impractical pair of sandals that he quickly replaced and went across the country to Washington, DC, and then on to 323 other countries, island groups, and territories. He set a Guinness World Record for longest ongoing pilgrimage and kept going for several more decades after that. He carried his cross all over the world for more than 50 years.

In his not-so-humble moments, Blessitt called this “one of the most dramatic and enduring pilgrimages in the history of man.” But he would also say his own role should not be overinflated. What had he done, except walk? Except be obedient to the voice that told him to go?

“I was just a donkey and pilgrim, lifting up the cross and Jesus,” Blessitt said.

Everywhere he went, people asked him to explain himself, and he told them about Jesus.

The evangelist died on January 14, 2025, at the age of 84. In a final statement posted to his website, Blessitt said he was looking forward to walking in glory.

“These feet that walked so far on roads of dirt and tar will now be walking on the streets of gold,” Blessitt wrote. “Ready to see Jesus again!”

Blessitt was born on October 27, 1940, in Greenville, Mississippi, to Virginia and Arthur Blessitt. The elder Arthur served in the Air Force in World War II and was stationed afterward in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Louisiana again.

The family was not especially religious but attended a Baptist revival when young Arthur was 7. It was held in a bush arbor—a temporary structure in the woods, made of brush and branches piled on top of fresh-cut poles—and the boy wanted to go forward during an altar call. Blessitt’s parents said he was too young to make a decision for Jesus. On the way home, as he recalled in his memoir, he pleaded and pleaded until his father hung a U on the dark Louisiana road, headed back to the revival, found the minister about to leave in his car, and said, “My son wants to give his life to Jesus.”

Blessitt told everyone he knew about his newfound salvation, leading his sister to Christ and handing out tracts and talking about Jesus in the bars where his father went to drink—until the elder Arthur, too, accepted Jesus.

Blessitt felt a call to ministry when he was 15 and went to Mississippi College and then Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary to prepare. He got ordained in a Baptist church and lasted one semester in seminary before feeling compelled to spend all his time evangelizing.

He ended up in Elko, Nevada, preaching in the brothels that were legal in the state, and then in Los Angeles, where the 1960s counterculture was exploding. In West Hollywood, he found a whole generation experimenting with drugs and music, new lifestyles, and new ideas, all searching for something better than their parents had given them.

“Kids are totally disillusioned with the phony concept of life,” he told a British reporter seeking to understand the hippie phenomenon. “They are contemptuous of the great American dream of money, two cars in the garage, cooler TV, coziness, and complacency. Jesus offers life: L-I-F-E.”

Blessitt, experienced at evangelizing in bars, made his way through the clubs on the Sunset Strip, including the famous Whisky a Go Go, before deciding to start his own: a nightclub for Jesus.

It was a safe and free place for people to go—strung-out kids, street hustlers, bikers, drug dealers, drag performers, and rock musicians. Blessitt gave out coffee, Kool-Aid, bagels donated by a Jewish deli, and New Testaments with psychedelic-looking covers. His wife, Sherry, said he should call it “His Place,” so he did, and he made a big cross to hang on the wall.

The cross came down when His Place was evicted by the landlord. Blessitt carried it outside, chained himself to it, and announced he was going on a hunger strike to protest this blatant attempt to banish Christian witness from Sunset Boulevard. He fasted for 28 days, Blessitt later wrote, before the owner of another building offered him a building for His Place.

Blessitt was only in the new location for a little while, though, when he heard Jesus speak to him.

“Not in an audible voice,” Blessitt later explained, “but in my heart and mind. I know HIS voice.”

Jesus said, “I want you to take that cross that is hanging on the wall in His Place and carry it across America.”

Blessitt said, “Thank you, Jesus, wow!”

There were lots of reasons to think this was a bad idea, but the 29-year-old evangelist was committed to being obedient to what he heard God say, regardless of the consequences. A few hundred people, including his wife and young children, gathered to see him start off on Christmas Day 1969. He led the crowd in a chant:

“Give me a J.”

“J!”

“Give me an E.”

“E!”

He spelled out Jesus and then asked, “What does that spell?”

The crowd said, “Jesus!”

Blessitt said, “What does America need?”

And they answered, “Jesus!”

He headed to DC. It wasn’t only the nation’s capital that needed Jesus, though, so after arriving in the summer of 1970, Blessitt decided to continue to Florida. But it wasn’t only America, either, so he went to Canada, and then to the ends of the earth.

Blessitt wrote about his journeys in his diary and later his memoirs with boundless cheerfulness. He had an apparently inexhaustible optimism for what he believed God was doing and always ran into people ready to hear how Jesus loved them. He told stories of amazing encounters, dramatic conversions, and miracles. Though ordained a Baptist, as time went on he increasingly spoke like a charismatic.

“Well, TODAY THE GLORY FELL!” he wrote in the late 1980s. “I know it’s strange, but there is a moment on almost every walk in every country where the glory comes, when there is liberty—there is a breakthrough.”

Following the Spirit could be dangerous. Blessitt wrote that someone tried to set his cross on fire in Indiana and a group of men on motorcycles stole it in Assisi, Italy. He was thrown in jail multiple times and assaulted by police at least once. He was chased by an elephant in Tanzania, a crocodile in Zimbabwe, a green mamba in Ghana, and men with stones in Morocco.

In America, he was shot at several times. Once, Blessitt said he jumped in a ditch and hid. Another time, he didn’t know why he hadn’t been hit. Maybe the men just missed, he reflected later, or maybe an angel had intervened, deflecting the bullets.

Blessitt ignored a doctor’s advice to get surgery for an aneurysm when he first set out and was fine, which he considered a miracle. He made up his mind to ignore all danger from then on. If he believed he was called by God, that overrode everything else.

“The call of God is not conditional,” Blessitt wrote. “I’d rather die in the will of God than live outside it.”

That commitment wasn’t a burden, for Blessitt, but a great adventure. People didn’t realize how exciting it could be to serve Jesus, he said. When he thought back at the end of his life to what he’d done and where he’d been, he couldn’t help but exult.

“Thank you Jesus for calling me to evangelism,” Blessitt wrote. “I have preached in houses of prostitution, homosexual churches, Hell’s Angels camps, rock festivals, in bars, nightclubs, go-go clubs, nude clubs, love-ins, on the streets, on sidewalks, on porches, in football stadiums, at automobile races, wrestling matches, dirty movie-porno clubs … even an occasional church!”

Blessitt is survived by his first wife, Sherry; his second wife, Denise; sons Arthur Joel, Arthur Joshua, Arthur Joseph, and Arthur Jerusalem; and daughters Gina, Joy, and Sophia.

He asked that there be no funeral or memorial services.

“The greatest thing you could do would be to go out and lead one more soul to be saved,” Blessitt said. “Share Jesus with someone today.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated Blessitt’s age at his death.