When the government put its abortion ban up for a referendum vote seven years ago, Evangelical Alliance Ireland executive director Nick Park and his team crisscrossed the country to speak at Catholic Masses about the issue.

Now, the evangelical advocates say they are ready to launch a similar tour across Irish churches if assisted dying comes up for legislative debate.

In a country with a history of deep sectarian divides, the pro-life cause remains a source of unity and shared convictions among Christians in Ireland. As the neighboring United Kingdom advances a bill to allow terminally ill patients to end their lives, Ireland’s Protestant and Catholic leaders have grown more concerned about the issue and the possibility of similar moves degrading the value of life in their own country.

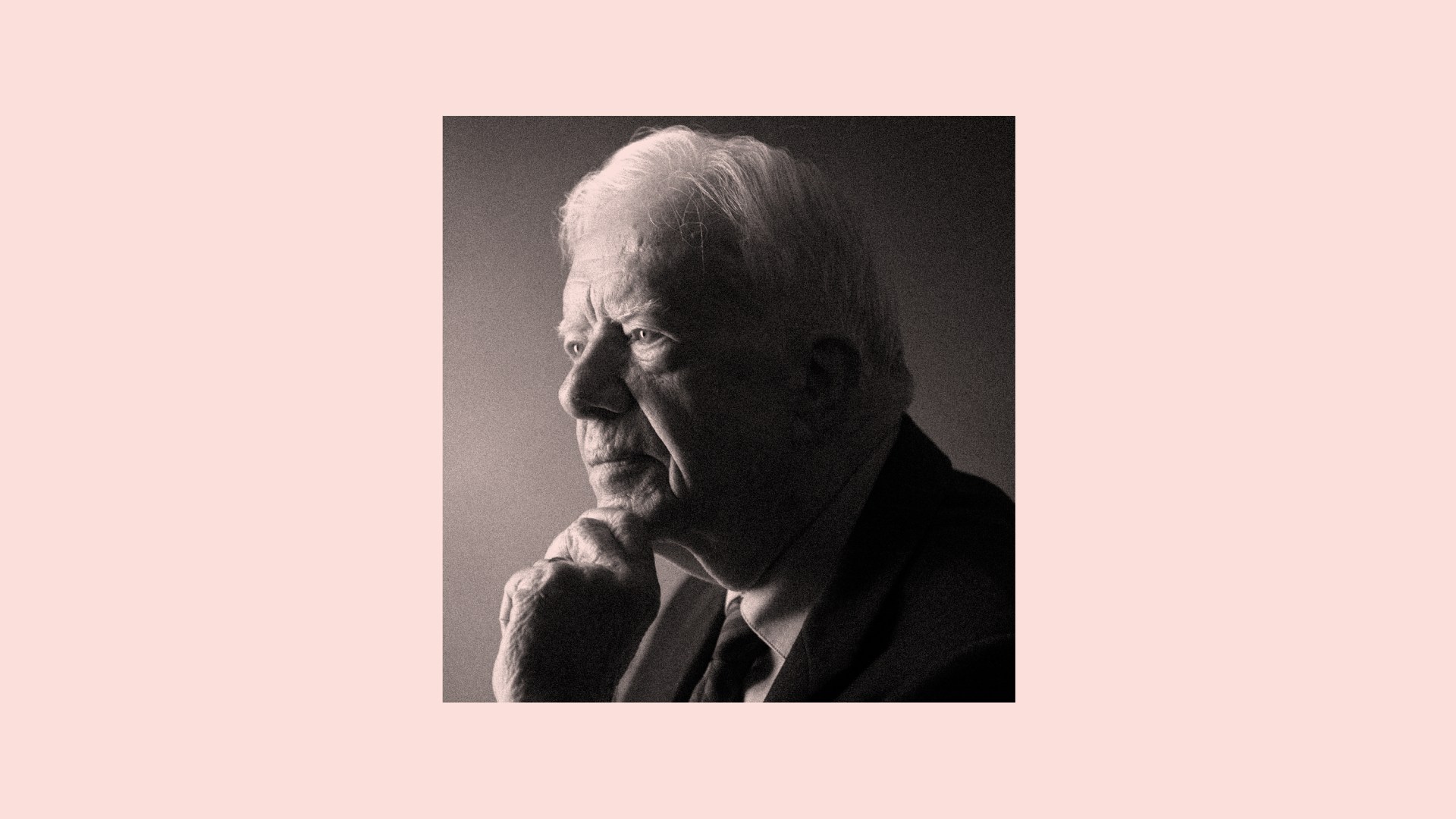

“I think it would be an absolute tragedy,” Park said in an interview. “Once you start chipping away at a basic core gospel principle that human life is sacred, it has unforeseen consequences.”

Last March, the Irish legislature’s Joint Committee on Assisted Dying published a report recommending that assisted dying be legalized in certain restricted circumstances. In October, the Dáil, the lower house of the Irish legislature, voted 76 to 53 in favor of noting the report, a move that drew criticism from Christians across the country.

In response, Catholic bishops in Ireland called on members of the church to advocate against such proposals.

“Assisted suicide, far from being an expression of autonomy, is a failure of care,” they wrote. “By legislating for assisted suicide or euthanasia, the State would contribute to undermining the confidence of people who are terminally ill, who want to be cared for and want to live life as fully as possible until death naturally comes.”

A bill to legalize assisted dying was proposed in the Dáil, but the dissolution of the legislature and the ensuing November 29 general election precluded any deliberation on it.

The election results could decrease the chances of legislation on assisted dying or at least delay such proposals for months: The key sponsor of the previous assisted dying bill lost his seat in the election, and the two parties that won the most seats are consumed with the task of forging a coalition government.

Still, faith leaders in Ireland worry that the recent vote in the UK could renew momentum for a similar movement in Ireland. A recent poll conducted by the Irish Examiner found that 57 percent of people in rural Ireland support legalizing assisted dying, while 21 percent are opposed.

When the UK bill was being debated, the Methodist Church in Ireland released a statement saying, “Once assisted suicide is approved by the law, a key protection of human life falls away.”

The Church of Ireland, which is the country’s largest Protestant denomination, argued that legalizing assisted dying would put pressure on the elderly and other vulnerable populations to end their lives.

“As Christians we believe that all life is created in the image of God, as a gift from Him, and has intrinsic value, regardless of who we are, our personal circumstances and our abilities and limitations,” its statement read. “If we accept that, in some cases, there are those who by means of age, disability or illness would qualify for assisted suicide, have we not judged their life to have less value?”

Dr. Michael Trimble, a consultant in acute internal medicine with the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast and a member of the Church of Ireland’s Church and Society Commission, said in an interview that legalizing assisted dying in Ireland would likely have a detrimental impact on vulnerable populations. (The UK bill currently does not apply to Northern Ireland, and a majority of the Northern Ireland members of Parliament voted against the UK bill.)

“Once you’re over the line that assisted suicide is acceptable, then the slippery slope is very real,” Trimble said, “If you cross the robust barrier of ‘We don’t kill people,’ it’s very hard to put up any other barriers that are strong enough to withstand challenge.”

“If the church is not speaking out on behalf of the vulnerable, then it’s failing in its mission,” he added.

Park said his organization is prepared to coordinate with both Protestant and Catholic communities to advocate against future proposals for legalizing assisted dying.

“It’s been a key cornerstone of Irish society for a long time that people that are ill, people that are disabled, people that have a life that some would say is a lower quality of life, are actually very special and have a lot to contribute to society,” he said.

Approving assisted dying would be a drastic departure from how Irish society has treated vulnerable people in the past, Park said.

“When you have somebody with special needs, the Irish-language term for that person is literally translated as ‘child of God.’ And I think that shows something about where the Irish heart has always been,” Park said. “But now this idea that somebody, because of terminal illness, that their life isn’t as important, that would be quite a shocking turnaround for us.”