When my friend Dima is kept awake at night, he goes out onto his eighth-floor apartment balcony in Kyiv’s eastern suburbs to pray. In the skies above, wave upon wave of Iranian-made Shahed drones pass overhead—Kyiv’s eastern flank is the most vulnerable to air attacks. With panoramic views of the city, Dima silently watches and prays.

The roar of the drones is considerable. They are nothing like the flimsy, pocket-sized photographers’ gadgets I had envisaged before my visit last September. Shahed drones come in various models, but perhaps the most feared are the large, triangular ones: They are the height of a tall man and resemble miniaturized stealth bombers. Each is packed with explosives, and they arrive in overwhelming numbers. The Ukrainian people must endure aerial bombardment night after night.

Dima works for his local church in outreach and youth ministry and naturally has much there to pray about. But as drones tear across the sky, it is impossible not to pray for equally pressing concerns: for lives to be spared and for drones to be shot down. Surely such aims must take precedence in both life and prayer.

Eighty-six years ago, C. S. Lewis wrestled with similar questions. After Germany refused to back down from its invasion of Poland, Great Britain and France declared war in September 1939. The following month, Lewis, the Oxford literary scholar, found himself preaching a sermon he titled “Learning in War-Time” on the first Sunday of the academic year. He chose to tackle a question that would have troubled everyone present in the congregation that day: How could they continue academic pursuits now that there was “a war on”? Lewis’s response offers wisdom that is remarkably relevant still, not only for the likes of Dima in Ukraine but for us all.

When I first saw the images of hundreds of Russian tanks bearing down on Kyiv in February 2022, the many Ukrainian friends I had come to respect and love quickly came to mind. I had visited the country several times, beginning in 2016, as part of my work for Langham Preaching, a program of Langham Partnership started by John Stott in 2002 to develop grassroots expository preaching movements, now in more than 100 countries.

I met Sergiy Tymchenko, a Baptist pastor and founding director of Realis (the Research Education and Light Center). He had encountered Stott soon after the Soviet Union’s collapse and, in due course, was named a Langham Scholar to do a PhD in public theology in Britain.

The very notion of theological engagement with the public square was inconceivable under Communism, and afterward still suspect. So Sergiy’s vision seemed alien to those who, like him, had grown up under the Soviet Union’s antireligious ideology. But he was committed to serving Ukraine’s church and society as various needs arose in those exciting and troubling years. That meant developing counseling training programs, which were almost nonexistent in churches at that time. Since invasion has now traumatized an entire nation, this vision was sadly prescient.

Furthermore, the war has also proved the wisdom of Sergiy’s passionate support for introducing chaplaincies (military, prison, and hospital) into Ukrainian life. These had been inconceivable in a culture forged by decades of Communist atheism.

The primary focus of our collaboration, however, came through Sergiy’s desire to enhance local church ministries across Ukraine. We began seminars in earnest in 2017 in Irpin, near the Realis Center in western Kyiv.

So when the BBC showed footage of Ukrainian forces’ defensive destruction of an Irpin bridge in 2022, as well as news of the most appalling atrocities in neighboring Bucha, everything suddenly gained horrific proximity for me.

Lewis knew war from firsthand experience. He matriculated at Oxford in the summer of 1917, knowing his undergraduate studies would be curtailed by the Great War, then in its third year. After volunteering for military service and completing his basic training at Oxford, Lewis was commissioned as a junior officer and plunged into the infamous trenches at the Somme in northern France. He remained there for the next five months until being wounded by friendly fire and invalided out in April 1918.

That conflict left an indelible mark on Lewis and his generation. Lewis was no pacifist even before his Christian conversion, but he did later say he respected, despite disagreeing with, those who genuinely were.

The fact that Lewis volunteered to serve in the war lends his October 1939 sermon a greater moral authority. That address, given at University Church at St Mary the Virgin in Oxford, was published under the title “Learning in War-Time” in The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses.

Could the university even justify staying open, Lewis asked? Perhaps it was more sensible to close the humanities’ faculties to assign every resource to the war effort. After all, how on earth might the study of Petrarchan sonnets, J. S. Bach’s masterpieces, or Renaissance portraiture possibly defeat Nazism? Such were the insecurities circulating in many university towns as Lewis ascended St Mary’s grand pulpit.

Although Lewis did not expound a biblical text, there is no doubt that everything he said was grounded in his Christian faith. But that is not where he began:

A university is a society for the pursuit of learning. … Why should we—indeed how can we—continue to take an interest in these placid occupations when the lives of our friends and the liberties of Europe are in the balance?

I found myself asking a similar question last year, after the UK Foreign Office eased its travel advice for western Ukraine. I was desperate to see friends but anxious not to compound burdens. I had never visited, let alone ministered in, a war zone before. Was it appropriate to be there in any capacity as a noncombatant?

As I reread “Learning in War-Time,” not only did it provide impetus for my two-day preaching workshop and weekend seminar on the importance of the arts in wartime; Lewis’s sermon became the subject of a lecture in its own right.

A key question we must answer is: What has the war changed? Pose that question to any Ukrainian, and the response is, invariably, “Everything!” No doubt those suffering the aftermath of a hurricane, the effects of seismic economic challenges, or communal grief after a mass killing can relate. Those from Ukraine’s east have endured the destruction and occupation of entire communities since Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea.

Once the full invasion was launched, millions fled the country to uncertain futures. Whether they left or stayed, nothing could ever be the same again.

During my visit last year, it was certainly a shock for this privileged Brit to experience nightly air-raid sirens for the first time, despite locals appearing to barely acknowledge them.

Reminders of war were pervasive. Highway billboards still advertised the same old stuff—new cellphones or kids’ fashions—but they were now juxtaposed with recruitment posters for regiments or drone squads. Every few miles in Kyiv’s outskirts, soldiers loitered at military checkpoints as the regular commuter traffic flew past; but roadblocks with antitank defenses, affectionately known as Czech hedgehogs, could be retrieved from the roadside and made operational in seconds.

In the center of Kyiv, I was relieved to see how intact the historic districts remained. Sergiy and I made the most of the autumnal sunshine, taking long walks across the magnificent city. We entered a large Baptist church in his neighborhood, one whose history dates to before the Soviet era. Its reverberating foyer contained the usual noticeboards of schedules and study topics. But one wall now presented color photos of roughly 40 men in military fatigues and, at its base, a row of four in stark monochrome: the fallen. All were members of this congregation.

During my 10 days in Ukraine, I did not meet a single person without friends or family at the front. Almost all had lost someone. Everything had changed.

Alamy

Alamy Getty

GettyRead against the backdrop of lethal drones and aching grief, Lewis’s sermon makes a startlingly insensitive—and perhaps offensive—point. Lewis insisted that nothing has changed. It is important, he said, “to try to see the present calamity in a true perspective. The war creates no absolutely new situation; it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it.”

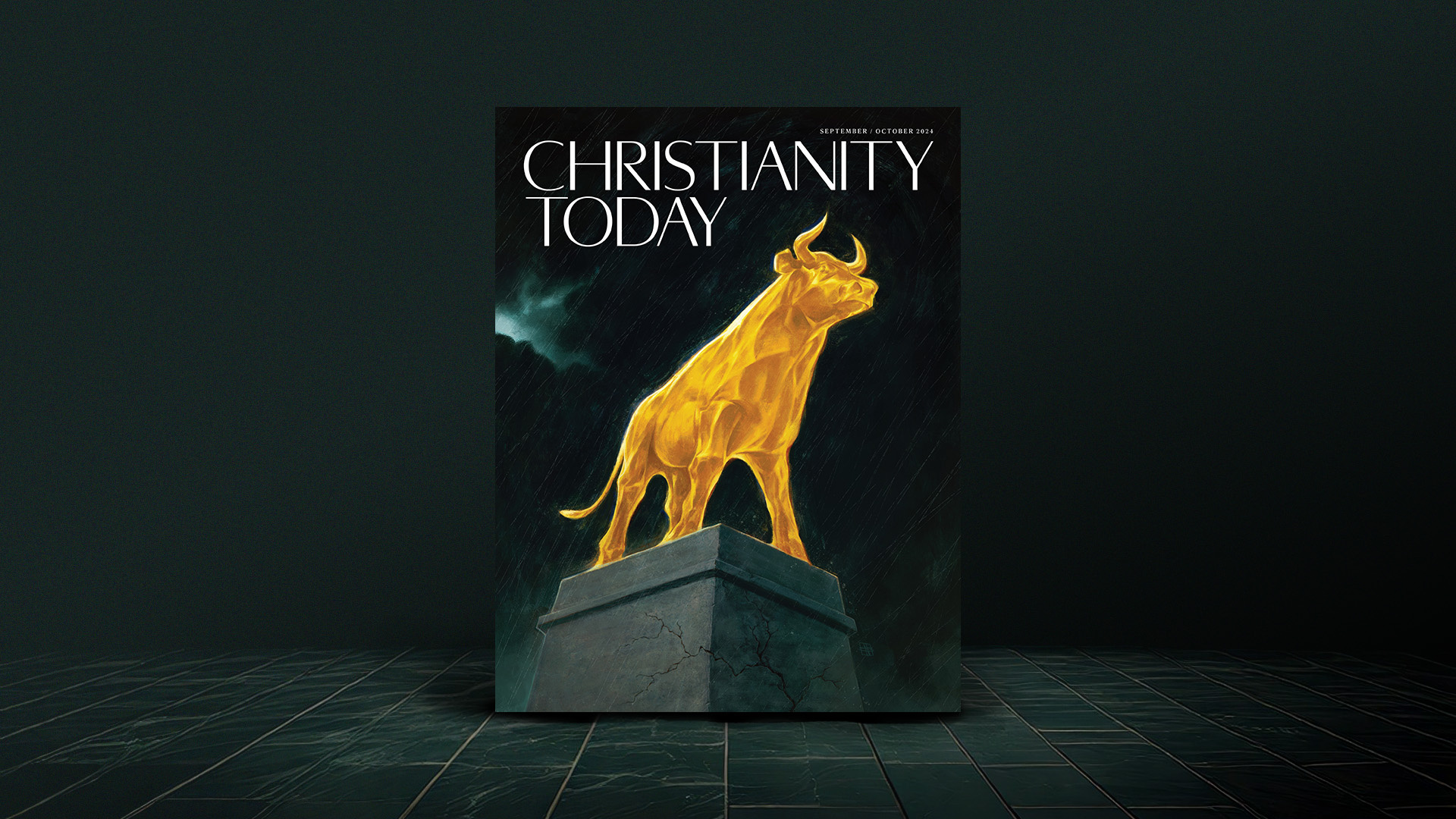

The key to his argument comes from his surprising entry point. After suggesting that the challenge of academia during a war could be considered akin to the proverbial Nero who fiddled while Rome burned, Lewis dared to mention what he called the “crude monosyllable” of hell. His justification was the teaching of the Lord Jesus himself, and his reason was that an eternal perspective is essential to his entire argument.

The reality of divine justice offers the ultimate benchmark for what is of true and lasting value. Neither the Second World War nor the Russian invasion of Ukraine—nor the current horrors in the Middle East—makes the slightest difference to that. That may sound glib to those suffering, yet it does not alter the fact of it. Lewis’s point is simply that eternity has always been life’s ultimate measure, war or no war.

The crucial question, therefore, is not which activities may be justified in wartime but which activities are worth doing at any time. For something to be worth doing, it must have inherent value, whatever the circumstances and despite human mortality.

This doesn’t mean that wartime doesn’t influence our work and our perspective. “Yet war does do something to death,” Lewis continued. “It forces us to remember it.” This is certainly happening in Ukraine.

Andriy is a Kyiv pastor who was previously a well-known journalist. He regularly visits the frontline and field hospitals as a volunteer chaplain. He was in no doubt of Lewis’s point. Before the war, many people were noncommittal or even resistant to matters of faith. It is entirely different now. Andriy barely has a single conversation with the active or wounded that does not concern eternity and divine justice.

Another friend of mine, Sasha, in Lviv, learned three days before we met that one of his oldest Christian friends had been killed at the front. His grief was intensified by the impending birth of his first child. Quietly agonizing, Sasha said in English, “Just what kind of world are we bringing him into?”

In light of such horrors, not devoting everything to the war effort can seem frivolous at best and obscene at worst. Surely our attitude must be all hands on deck? Maybe not. Lewis’s approach is carefully reasoned, working through a perspective that would seem absurd to nonbelievers but compelling for believers.

Because Christ sacrificed everything for us, it stands to reason that he deserves our everything in response (1 John 3:16). Consequently, only one object is worthy of our total devotion: God himself. Lewis insisted nothing else comes remotely close, be it a career, a family, an academic pursuit, or even a war effort. Lewis illustrated this with the concept of training to become a lifeguard, an inherently good thing to do:

We may have a duty to rescue a drowning man and, perhaps, if we live on a dangerous coast, to learn lifesaving so as to be ready for any drowning man when he turns up. It may be our duty to lose our own lives in saving him. But if anyone devoted himself to lifesaving in the sense of giving it his total attention—so that he thought and spoke of nothing else and demanded the cessation of all other human activities until everyone had learned to swim—he would be a monomaniac. The rescue of drowning men is, then, a duty worth dying for, but not worth living for.

The analogy is apt for Ukrainian forces desperately fighting to defend their country, as well as for any nation or community facing peril on a grand scale. How can we avoid becoming obsessive, especially at perilous times? Lewis’s solution is to ensure we do everything “as working for the Lord” (Col. 3:23). This Pauline principle subverts the old sacred-secular divide by insisting that a life of sacrificial worship embraces far more than just the “holy” or religious parts of life. It is a matter of whole-life discipleship.

Furthermore, as creatures created in God’s image, we long for what is true, beautiful, and good. As Lewis wrote, “An appetite for these things exists in the human mind, and God makes no appetite in vain.” So it is no accident when some seek to plumb the depths of truth, beauty, and goodness. That is inherently worth doing, war or no war.

Now, a country at war faces unique demands. Conscription is perhaps necessary, and it necessarily rips people out of their everyday lives. Lewis was not arguing for the precedence of academic study; his understanding of just war theory would suggest that there are circumstances when it is right to take up arms. He was simply saying that academic study, even study of the humanities, during wartime (albeit for a minority) is a legitimate vocation. If something is justifiable in peacetime from an eternal perspective, it is entirely justifiable in wartime.

This does not mean everybody will grasp this. I know that my grandfather, ordained to Church of England ministry not far from Oxford in 1940, often encountered incredulity and even hostility after the war years when explaining his lack of military experience.

So it was very moving to chat with a Ukrainian man I’ll call Petro as our Realis seminar closed. He had come at the last minute, despite being a senior energy specialist with responsibility over several power stations in Ukraine’s bitterly contested east. Two days before the seminar, one of his facilities was almost completely destroyed in a Russian attack. He assumed that leaving it would be impossible. On inspection the next morning, however, there was simply nothing he could do to repair it. He looked exhausted and hollowed out when he arrived at the seminar.

After three days, however, Petro seemed a little brighter. “Thank you so much for being willing to come to Ukraine,” he said through Andriy’s interpretation. “We need this. We need to learn more about preaching. We need to learn about what is beautiful in the world. Even now. Especially now. These things matter more than ever.”

I then remember Dima, praying on his balcony as drones fill the skies. Lewis’s perspective must resonate with him as he brings his requests before God. Yes, he prays for war to end. But he also prays for all the things that make life rich and livable, war or no war.

Mark Meynell has been director (Europe and Caribbean) for Langham Preaching since 2014. In 2025, he is focusing his attention on writing and teaching while serving as an associate of Langham Partnership. He writes at markmeynell.net.