In 1998, I found myself in a prison chapel. I had been in a chapel like this before, to coldly negotiate with a God I barely trusted, but there was something different this time.

I was jittery as I sat down and looked around at the other inmates singing unfamiliar songs. Instead of joining them, I let my mind drift back to all the things that had gone wrong in my life. It was an extensive list. I was a drug lord at the end of my rope.

The singing ended, and the preacher got up behind a makeshift pulpit. As he read Psalm 139, something inside me began to shift. O Lord, you have searched me and you know me. The words broke through the miserable fog in my brain and birthed an unexpected sense of peace.

It was the first time I had ever known such peace. And it would change my life.

I grew up as the youngest of five boys in an immigrant family. My parents had made their way from the Dominican Republic to the United States in 1965 after the assassination of President Rafael Trujillo.

Raising five boys was sometimes overwhelming for my parents as they worked constantly to meet the demands of life in New York City, especially with a language barrier. My mom, a practicing Catholic, and my father, a Protestant, tried to instill Christian values in us rowdy boys, and I attended church at an early age. But I only understood Christianity superficially at that time.

In the early ’70s when I was a teenager, I thought if I could dress and act a certain way, I’d be accepted by the other kids in the diverse neighborhood of Queens where I lived. Things took a bad turn, though, when I started fighting with other kids and experimenting with marijuana and other drugs.

My brother Emilio was in a gang, and I admired his emblemed jacket, his cool sense of belonging and power. I wanted to be like him. So when I was 13, I joined a gang too. There were thrilling moments but also terrible ones—like the day I witnessed my gang leader get shot and killed. But it wasn’t enough to turn me away completely, and before long, I landed in juvenile detention for robbery.

In high school, I thought I had changed my ways after meeting Alexandra, the girl who would become my wife. We eventually married and had our first child, but we were buried under financial problems. I began thinking that if I connected with Emilio, who was then involved in drug distribution, I could make things right at home.

And so I began to immerse myself in the ins and outs of drug trafficking. I eventually oversaw the whole eastern seaboard. Millions of dollars passed through my hands. I became a drug baron, living in luxury and excess, glutted on parties, mansions, celebrities, women.

Our financial problems were gone, but now there were other troubles. For one, I was always looking behind my back with apprehension. Would I get caught?

My fears were realized in 1996. Police arrested me and seized $3.8 million worth of cocaine, and my drug kingdom collapsed.

After much negotiating, my attorneys were able to reduce my life sentence. One day while in prison, I went to the chapel, thinking I could also negotiate with God to further intervene in my case. I was used to working things so that I’d have my way. I bargained with God, saying if he allowed me to be released earlier, I wouldn’t drink alcohol for six months. There were no words of repentance or a desire to seek him—it was pure selfishness, a transaction. Still, God heard my prayer. I was released from prison after only a year and a half.

That summer, I ran into an old acquaintance at a local bar. He turned out to be the second-in-command of a large cocaine distribution network for which Emilio also worked. We started talking, and the acquaintance offered me millions of dollars in cocaine if I wanted in.

My heart raced, thinking of the riches I could once again possess. The Bible says in Proverbs that as a dog returns to its vomit, so do fools return to their folly (26:11). In the same way, I accepted the offer and was once again involved in distribution.

But it’s not only dogs that return to messes. God does too.

That fall, I was arrested again, along with my brother Emilio, by the US Drug Enforcement Administration. I faced 18–25 years of incarceration in federal prison.

Shortly after, I was released on bail—but failed to report to my court appearance and became a fugitive. My life felt empty and void, and the little I knew about God seemed to fade. I felt the only recourse I had was to party all night and forget about my woes and worries. Though I wasn’t physically imprisoned, I felt trapped.

One night after getting drunk, I went home, knowing that would be the first place the cops would look for me. I was tired of being a fugitive, and the police found me in the morning. On my way to jail, I asked them to open the back door so I could end my life.

Little did I know that my brother Emilio, who had been in prison this whole time, had surrendered his life to Jesus at a chapel service. He had also prayed to God, pleading, “Lord, send my brother to the same facility where I am housed. I want him to know you as Lord and Savior.”

God answered that prayer. When I arrived at the facility, I was sent to the same housing unit as my brother. Emilio praised God when he saw me, but I responded by looking at him with indifference.

As the months passed, I grew increasingly depressed. My wife had left me, my friends had abandoned me, and I was desperate for a way out. But Emilio refused to let me wallow in self-pity. One night, he said, “Come to the service with me. God can help you through this.”

I shrugged. I needed help from something or someone. Why not God? I had once trusted God, however imperfectly, to get me out of jail. Even though I had strayed far from him since then, maybe this time he could do something about the ache inside me that wouldn’t go away.

And so I found myself in the prison chapel once again.

The preacher explained that whatever had landed us in prison was a result of sin and that God wanted to give us peace and salvation. He quoted Romans 5:8: “God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” He said, “Christ wants to meet you right now.”

It was as if his words were meant just for me. I couldn’t help but reflect on all the things I had done or experienced in my life and where they had led me—prison, literally and figuratively. Even if I escaped from prison, I could never escape the prison of my past. Just as that thought formed in my mind, the preacher said, “God has a way out for you.”

My heart pounded hard in my chest. Did God tell him to say that?

The preacher continued, “God wants you to know that he can fill that void. Christ can make you a new person.” The fog cleared in my mind. When the preacher invited us to come and pray, I walked to the front of the chapel and fell to my knees, sobbing.

The weight of my sins and their far-reaching consequences hit me. I thought about all the people I had wronged, the lives wrecked by addiction, my broken family. I said, “God, forgive me.” As the words tumbled out, a warmth enveloped me. It felt as if God had physically reached inside me, taking out all the guilt and shame, all the dark deeds, and filled that space with light. He had answered my prayers and saved me when I least deserved it.

I became a new man. I realized that all the drugs, alcohol, and wealth couldn’t compare to the immense love and peace of God. All I wanted was more of God, more of Jesus. Even though I was still in a physical prison, I was spiritually free in my mind, body, and soul. Praise the Lord!

Things were still hard, though, especially when it came to my marriage with Alexandra. After many months of sending letters to her and of my parents trying to intervene on my behalf, God stepped in. I remember fasting and praying for my wife for three days. On the third day, God answered my prayers yet again: She came to see me.

My wife wanted a divorce. But I shared about the hope within me and said that Jesus could give her the same experience of true freedom. I went on to tell her that even if she left me, Jesus loved her, and that all I wanted for her was salvation.

Alexandra began to cry and said, “I want what you have—I see you in such peace.” She continued, “My life is a mess. I drink all day and night, and I have also been unfaithful to you.” As we confessed our sins to one another, God began to restore our marriage right then and there. And, best of all, Alexandra accepted Jesus as her Lord and Savior too.

Today, I am an author, pastor, and speaker, sharing hope in chapels, churches, and venues around the world about the one who heard my prayers and saved my life, Jesus Christ. I have spoken to children and college students, law enforcement officers and governors. Christ has shown me that the hands that were once used to destroy people’s lives are now being used to restore and build up others in Jesus. My life is Christ and Christ alone! This is who I am now.

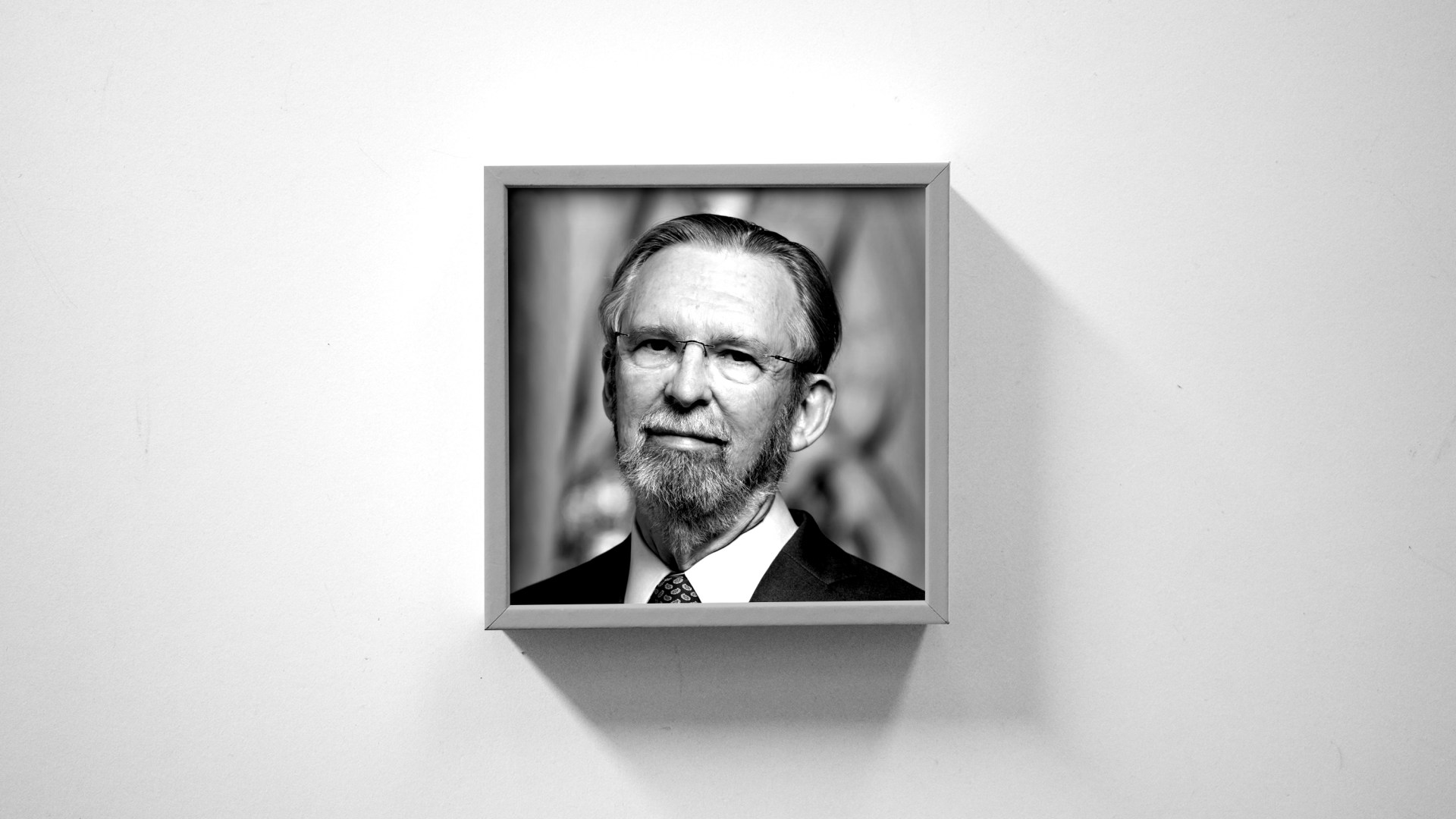

Herman Mendoza is lead pastor of Iglesia Promesa Internacional, director of PowerHouse Kids Ministry, and author of Shifting Shadows: How a New York Drug Lord Found Freedom in the Last Place He Expected. His story has been adapted into a film, Drug Lord’s Redemption.