American journalism experienced a minor apocalypse in January.

The Los Angeles Times laid off more than 20 percent of its newsroom. Time cut 15 percent and Business Insider 8 percent. The Wall Street Journal laid off 20 people in its DC bureau. Sports Illustrated laid off so many people that it is expected to close entirely. Pitchfork, also subject to mass layoffs, already closed up shop as an independent outlet and will now exist as a subsection of GQ. And a news startup called The Messenger shut down entirely, after just a year in existence—though in that case, where $50 million in investments produced just $3 million in revenue, the story may be less about journalism than about simple mismanagement.

All told, more than 500 journalism positions went away last month, continuing a two-decade trend of industry contraction. Jobs and entire outlets are falling left and right—last year, an average of 2.5 newspapers shut down every week in the United States—and there’s no reason to think they’re coming back. Journalists can be hyperbolic and unduly self-flattering when talking about the decline of our industry, but it really is shrinking at a remarkable rate.

Still, I say January’s apocalypse was “minor” because this is but one round of many. A few months prior, it was The Washington Post shedding jobs. It’s always happening somewhere. Even a multi-outlet layoff and shutdown blitz like this one is but the sounding of a single trump. There will be more. In fact, as Post columnist Perry Bacon Jr. recently argued, it may not be too soon to say journalism will never be broadly profitable again.

I’m still hopeful that we’ll figure out a new business model, one that works in the digital era and doesn’t depend on advertising or social media, with all the unfortunate incentives they bring. But if that’s a pipe dream, as it may well be, I have a proposal for fellow Christians: Consider a journalism tithe.

It doesn’t have to be a literal tithe—though if you want to donate 10 percent of your income to support good journalism, don’t let me stop you. My actual suggestion, though, is less ambitious. It is simply that Christians should deliberately continue our long history of supporting writers (and artists and musicians) working to reveal, examine, and advance truth in our particular context. It is that we become patrons of journalism, and not only in the modern sense (I am a patron of this coffee shop) but in the older sense too—the kind of patronage that paid for the artistic flourishing of the Renaissance.

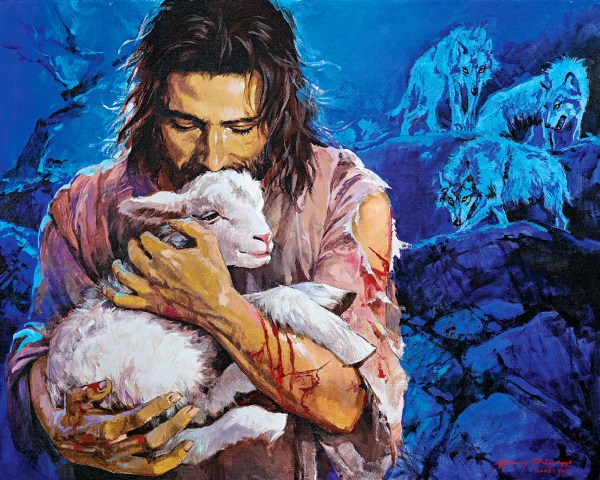

You may remember this model of arts funding from history class. In Renaissance Italy, as CT has noted, “Christianity, society, and art were inextricably linked. Works of art were not made to hang passively in museums. They were essential parts of the public landscape, with specific purposes,” including political and spiritual aims.

“Patrons who commissioned these works—whether popes, churches, monastic orders, town guilds, or individual citizens—did so because they knew that art was powerful. It could establish social status, assert authority, teach doctrine, evoke emotions, incite someone to prayer or action, and lead to social change.”

In our more literate culture, paintings and sculpture typically don’t play that role in the public square. Instead, for better and worse, journalism often does. So just like visual arts in the Renaissance, the style and content of journalism today is “not just a matter of taste. It [can] have profound—even eternal—consequences.” Patronage of good journalism can help keep this essential part of the public landscape focused on truth.

A few caveats are in order here. Most of us are not Medicis and will never have a Brunelleschi on the payroll. We will not fund the journalistic equivalent of il Duomo. By its nature, journalism is more ephemeral and time-bound. It is culturally influential in aggregate, but only rarely does any single article have lasting effect. Journalism will always be the sum of many little things. But it is worthwhile to be trustworthy with little things, to use even small amounts of money well (Luke 16:10–13; 21:1–4).

Another caveat is that much depends on that last word: well. I began reading Bacon’s piece expecting to disagree with his journalistic priorities, because his headline mention of “mission” journalism led me to think—in light of recent debates about journalistic norms and purpose—he’d call for activism in the guise of reporting.

I thought wrong. His actual recommendation is to prioritize three kinds of journalism: “Government and policy news, particularly at the local and state levels; watchdog journalism that closely scrutinizes powerful individuals, companies and political leaders; and cultural coverage, from important books and movies to faith and spirituality.”

This strikes me as exactly right, though I’d add two more specifications. One is that quality matters as much as topical focus. Bad journalism about politics and especially faith is worse than none at all. The other is that we needn’t exclusively patronize explicitly Christian journalism, but it should receive special consideration: “Why spend money on what is not bread, and your labor on what does not satisfy? Listen, listen to me, and eat what is good, and you will delight in the richest of fare” (Is. 55:2).

Finally, the obvious: I am a journalist saying you should give money to journalists. On this subject, I am as biased as they come. I think that journalism, for all its foibles and failures, plays a crucial role in a free society with a limited government; that it may need to evolve but should not be permitted to go extinct; that it is a powerful weapon in defense of religious liberty and other First Amendment rights; and that Christian journalism will only grow more needful as our society continues to secularize. Journalists are uniquely positioned to explain Christianity to a culture forgetting what it means.

Preserving journalism as an industry does benefit me personally, but these bigger goods matter far more than the future of my career. So don’t worry, I’m not going to end this with a link to my Venmo. You could, however, mosey over to CT’s donate page and start your patronage now.

Bonnie Kristian is the editorial director of ideas and books at Christianity Today.