As a professor, I discourage students from using smartphones during class. Nevertheless, they always pull them out as soon as class is over or during breaks in longer sessions. I feel this pull myself—the fear of missing something, the desire for dopamine. Perhaps we all need to practice better self-control. But clearly, our devices are designed to keep us hooked.

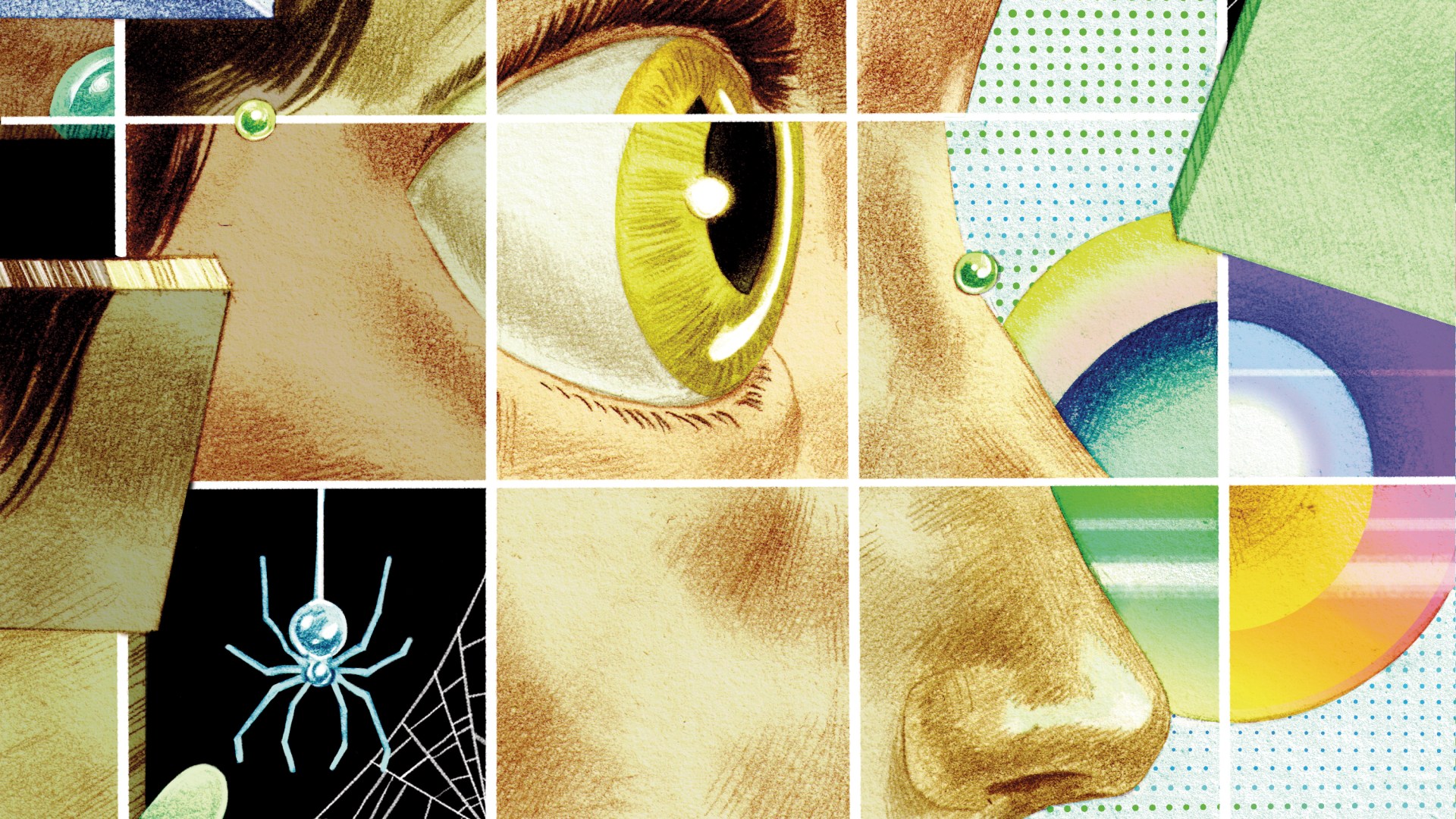

Hooks, like webs and nets, are meant to trap prey. This observation from Paul Kingsnorth captures the heart of his new book, Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity. For Kingsnorth, our screen addiction suggests a larger captivity to an “unprecedented technological network of power and control,” which he calls “the Machine.”

As Kingsnorth defines it, the Machine started as the basic ideology of modern life, best summed up as a preference for “the mechanical over the natural, the planned over the organic, the centralised over the local, the system over the individual and the community.” He sees it as the malign force behind slavery, colonization, overconsumption, and environmental degradation.

More recently, he argues, it has taken concrete form through technologies—especially digital technologies—that promise control but make us ever more dependent. Kingsnorth writes in an apocalyptic mode, seeking to unveil how we are losing our humanity—and calling us to resist before it is too late.

Kingsnorth is an English poet and essayist living in western Ireland. At one time he was an environmental activist who protested by “chaining [himself] to bulldozers” and “living in treehouses.” Nowadays, he channels those impulses into writing.

As a former practitioner of Wicca who (to his own surprise) converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Kingsnorth’s perspective does not fit cleanly into common political or theological categories. His current publisher positions him in “the tradition of Wendell Berry, Jacques Ellul, and Simone Weil,” and like these thinkers, he does not give anyone a free pass.

Against the Machine is a trenchant and terrifying account of what modern people have sacrificed in exchange for technology’s promise of power and autonomy. As Kingsnorth writes, “We have less agency, less control, less humanity than ever before. In the future that is offered to us we are not even cogs in the Machine, for the Machine can increasingly operate without human input.”

If this sounds a bit like science fiction, Kingsnorth wants readers to make the connection. He describes the 1999 film The Matrix as “the most symbolically prophetic film yet made about the 21st century.” Like the Matrix, he writes, the Machine is “designed to promote an illusion of freedom and choice to people who have neither.” In the film, humans exist primarily to power the artificial superintelligence that runs the world. Its genius is to absorb those who seek to resist.

Are we living in the Matrix? Not quite, though it is increasingly difficult to escape the hooks of our digital connectedness. My wife works in health care, and although our jobs have little in common, we share complaints about the comprehensive software “solutions” we’re compelled to navigate. When my university adopted a new software system from the Oracle Corporation, my colleagues and I joked about its name: “Let’s ask the Oracle.” “The Oracle will solve all of our problems.” “The Oracle is sending me on a journey.”

Technologies like these are designed to bring greater security and stability to increasingly complex professions and institutions. But do we really want the same software to manage hospitals, universities, and city governments? One “tech stack” to rule them all?

Perhaps this makes sense in economic terms. But it’s possible to discern a darker underlying logic, wherein a push for ever-improving outcomes dictates ever-greater efficiency—which, in turn, demands the imposition of ever-greater uniformity. Indeed, as I read Kingsnorth’s book, I thought of an 1869 lecture by the Dutch thinker Abraham Kuyper: “Uniformity: The Curse of Modern Life.” There is a difference, Kuyper argued, between organic, unplanned harmony and uniformity dictated from above (especially by the state).

Kingsnorth frames the curse of modern life with the language of uprooting. Traditionally, cultures have been anchored to what he calls the “four P’s”: our past (our history and ancestry), our people (the story of who we are), our place (our embeddedness in a particular setting), and prayer (our religious tradition). But the goal of the Machine, as Kingsnorth sees it, is detaching us from everything we know and love to rearrange people and cultures in a more uniform fashion.

This process replaces the four P’s with four S’s: science (which offers a “non-mythic” story of where we come from), the self (whose good we pursue above all else), sex (which provides the ultimate tool for expressing individual identity), and the screen (which distracts us from reality and directs us to “the coming post-human reality”). For Kingsnorth, this common ideology lies behind both progressive leftism and market liberalism.

The Machine might expand our menu of lifestyle options. Yet in embracing it, Kingsnorth argues, we unmake our humanity, losing our roots and plunging ourselves into a crisis of meaning. We have sought autonomy, but its price has been alienation—from the land, from each other, even from our own bodies. As Kingsnorth argues, proceeding along this path will destroy our planet, our cultures, and our homes, leaving us to gamble on new technologies to rescue us from the wreckage.

For Kingsnorth, the Machine is more than a metaphor. Artificial intelligence, in his view, embodies the spirit it has manifested since the Industrial Revolution. He notes how developers speak of AI as a form of intelligence they are “ushering” into the world, quoting Ray Kurzweil’s answer to the question if God exists: “Not yet.”

Rod Dreher recently suggested that ChatGPT is like a new Ouija board, a dangerous power we don’t fully understand. Kingsnorth entertains this as a serious possibility, drawing parallels between the spirit of the Machine and the spirit of the Antichrist. He believes “there is a throne at the heart of every culture” and something insidious “is crawling towards the throne.”

Many readers, especially those who have embraced new technologies, will find Kingsnorth’s project alarmist. By and large, I want to affirm the intrinsic goodness of technological innovation while resisting its idolatrous tendencies. Nevertheless, I find myself haunted by the dehumanizing—even diabolical?—tilt embedded in top-down systems (like Oracle), which by design treat people more like things. Kingsnorth has convinced me that careful theological reflection is needed on “principalities and powers” as they relate to our technological age.

Reflection, of course, is not enough. To what degree should we opt out of our digitally mediated world, seeking radically alternative forms of life? To what degree can we? Kingsnorth recalls a pilgrimage to Mount Athos in Greece. He was shocked to see monks with long beards and black robes tapping away on iPhones: “Even here, I thought, even them. If even they can’t make a stand, who possibly could?”

Indeed, Kingsnorth calls for resistance despite strongly suspecting the battle is lost. The West, he writes, is dead, and we are living in its ruins. Accordingly, we cannot rebuild large-scale civilizations, but only smaller communities on the margins, communities that embrace limits, lean into the local, and “learn again the meaning of worship and commitment.” As he writes, Westerners have to “learn how to inhabit again. We have to learn how to live sanely in our lands. How to write poems and walk in the woods and love our neighbours. How to have the time to even notice them.”

Such small interventions might seem unequal to the pervasive despair threaded through these pages. Yet the book reminded me of an insight from theologian Norman Wirzba: When we love particular places and particular people, we find space for hope. As Kingsnorth alternates between prophetic exposé and poetic lament, he revels in small things, in “community bonds, local economics and human-scale systems.” Perhaps he is not yet ready to hope; nevertheless, there are still things—and people—to love.

Still, as I consider my students, I wonder if they need a deeper hope, grounded not in the direction of our culture but in the covenantal love of the Creator for his creation—a living hope inspired most profoundly by the Resurrection. This hope helps us celebrate the good of creation and work for its continual renewal. It also reassures us that there are other powers at work in the world than the will of evil.

Kingsnorth begins with an epigraph from G. K. Chesterton. This makes it appropriate to recall some lines from Orthodoxy, where Chesterton says we are most human when joy becomes the most fundamental thing about us:

Melancholy should be an innocent interlude, a tender and fugitive frame of mind; praise should be the permanent pulsation of the soul. Pessimism is at best an emotional half-holiday; joy is the uproarious labour by which all things live.

In this spirit, we can rejoice that our world belongs to God; even the Machine is only an interlude. Resisting it might be grimly necessary. But in light of the Resurrection, our resistance can still be exhilarating.

Justin Ariel Bailey is a professor of theology at Dordt University. He is the author of Interpreting Your World: Five Lenses for Engaging Theology and Culture.