NEWS

MIDDLE EAST

Palestinian Christians are hopeful that recent confrontations will bring an end to Israeli domination.

Since December, conflict between Israelis and Palestinians has escalated into a grim stalemate with few signs of resolution. The violence has highlighted concerns among Palestinian Christians, many of whom feel that U.S. Christians wrongly support Israel uncritically.

Last month a Christian Zionist Congress convened in Jerusalem, calling on Christians to “come together to honor the Jewish state and pledge their ongoing support for her.” Meanwhile, the Middle East Council of Churches issued a statement designed to help Western Christians realize how Arab believers view their circumstances.

The council statement read in part: “The indigenous churches of the Middle East are keenly aware of the human rights violations presently inflicted on the unarmed Arab population of the occupied territories and Gaza, and they refuse to make God the author of such treatment.”

For Palestinians, Muslim and Christian, the recent unrest signals a fundamental change in tactics and self-understanding. Despite nearly 200 fatalities in the past six months, Palestinians report their morale remains high.

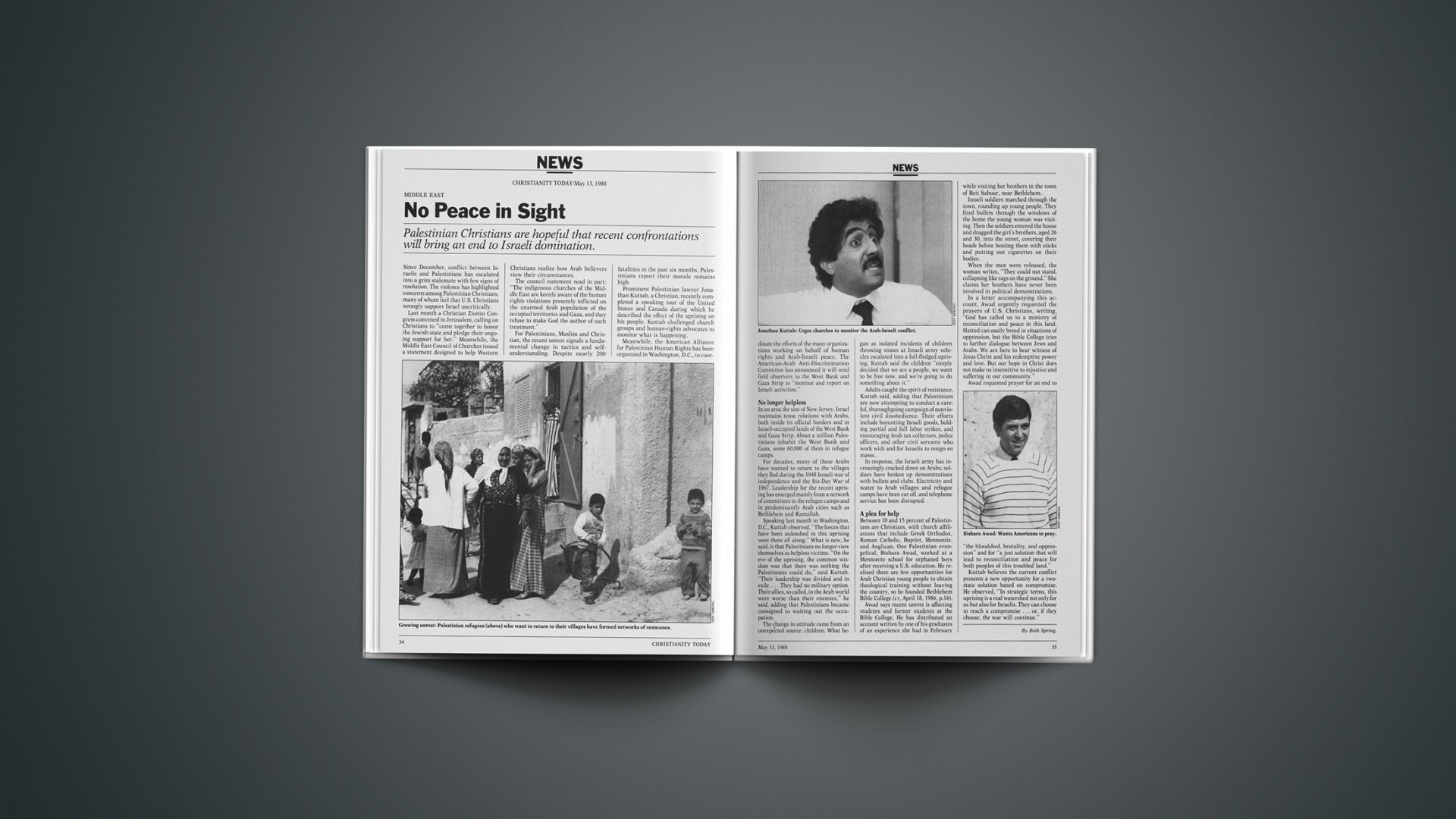

Prominent Palestinian lawyer Jonathan Kuttab, a Christian, recently completed a speaking tour of the United States and Canada during which he described the effect of the uprising on his people. Kuttab challenged church groups and human-rights advocates to monitor what is happening.

Meanwhile, the American Alliance for Palestinian Human Rights has been organized in Washington, D.C., to coordinate the efforts of the many organizations working on behalf of human rights and Arab-Israeli peace. The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee has announced it will send field observers to the West Bank and Gaza Strip to “monitor and report on Israeli activities.”

No Longer Helpless

In an area the size of New Jersey, Israel maintains tense relations with Arabs, both inside its official borders and in Israeli-occupied lands of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. About a million Palestinians inhabit the West Bank and Gaza, some 60,000 of them in refugee camps.

For decades, many of these Arabs have wanted to return to the villages they fled during the 1948 Israeli war of independence and the Six-Day War of 1967. Leadership for the recent uprising has emerged mainly from a network of committees in the refugee camps and in predominantly Arab cities such as Bethlehem and Ramallah.

Speaking last month in Washington, D.C., Kuttab observed, “The forces that have been unleashed in this uprising were there all along.” What is new, he said, is that Palestinians no longer view themselves as helpless victims. “On the eve of the uprising, the common wisdom was that there was nothing the Palestinians could do,” said Kuttab. “Their leadership was divided and in exile.… They had no military option. Their allies, so called, in the Arab world were worse than their enemies,” he said, adding that Palestinians became consigned to waiting out the occupation.

The change in attitude came from an unexpected source: children. What began as isolated incidents of children throwing stones at Israeli army vehicles escalated into a full-fledged uprising. Kuttab said the children “simply decided that we are a people, we want to be free now, and we’re going to do something about it.”

Adults caught the spirit of resistance, Kuttab said, adding that Palestinians are now attempting to conduct a careful, thoroughgoing campaign of nonviolent civil disobedience. Their efforts include boycotting Israeli goods, holding partial and full labor strikes, and encouraging Arab tax collectors, police officers, and other civil servants who work with and for Israelis to resign en masse.

In response, the Israeli army has increasingly cracked down on Arabs; soldiers have broken up demonstrations with bullets and clubs. Electricity and water to Arab villages and refugee camps have been cut off, and telephone service has been disrupted.

A Plea For Help

Between 10 and 15 percent of Palestinians are Christians, with church affiliations that include Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Baptist, Mennonite, and Anglican. One Palestinian evangelical, Bishara Awad, worked at a Mennonite school for orphaned boys after receiving a U.S. education. He realized there are few opportunities for Arab Christian young people to obtain theological training without leaving the country, so he founded Bethlehem Bible College (CT, April 18, 1986, p. 16).

Awad says recent unrest is affecting students and former students at the Bible College. He has distributed an account written by one of his graduates of an experience she had in February while visiting her brothers in the town of Beit Sahour, near Bethlehem.

Israeli soldiers marched through the town, rounding up young people. They fired bullets through the windows of the home the young woman was visiting. Then the soldiers entered the house and dragged the girl’s brothers, aged 26 and 30, into the street, covering their heads before beating them with sticks and putting out cigarettes on their bodies.

When the men were released, the woman writes, “They could not stand, collapsing like rags on the ground.” She claims her brothers have never been involved in political demonstrations.

In a letter accompanying this account, Awad urgently requested the prayers of U.S. Christians, writing, “God has called us to a ministry of reconciliation and peace in this land. Hatred can easily breed in situations of oppression, but the Bible College tries to further dialogue between Jews and Arabs. We are here to bear witness of Jesus Christ and his redemptive power and love. But our hope in Christ does not make us insensitive to injustice and suffering in our community.”

Awad requested prayer for an end to “the bloodshed, brutality, and oppression” and for “a just solution that will lead to reconciliation and peace for both peoples of this troubled land.”

Kuttab believes the current conflict presents a new opportunity for a two-state solution based on compromise. He observed, “In strategic terms, this uprising is a real watershed not only for us but also for Israelis. They can choose to reach a compromise … or, if they choose, the war will continue.”

By Beth Spring