Over the last decade, Southern Baptists have made little effort to disguise their civil war.

Moderates in the 14.6 million-member Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) have accused conservatives of waging a battle for political control. Conservatives say their political efforts are necessary due to growing liberalism in the SBC, reflected, they say, by the teachings and writings of some Southern Baptist seminary professors.

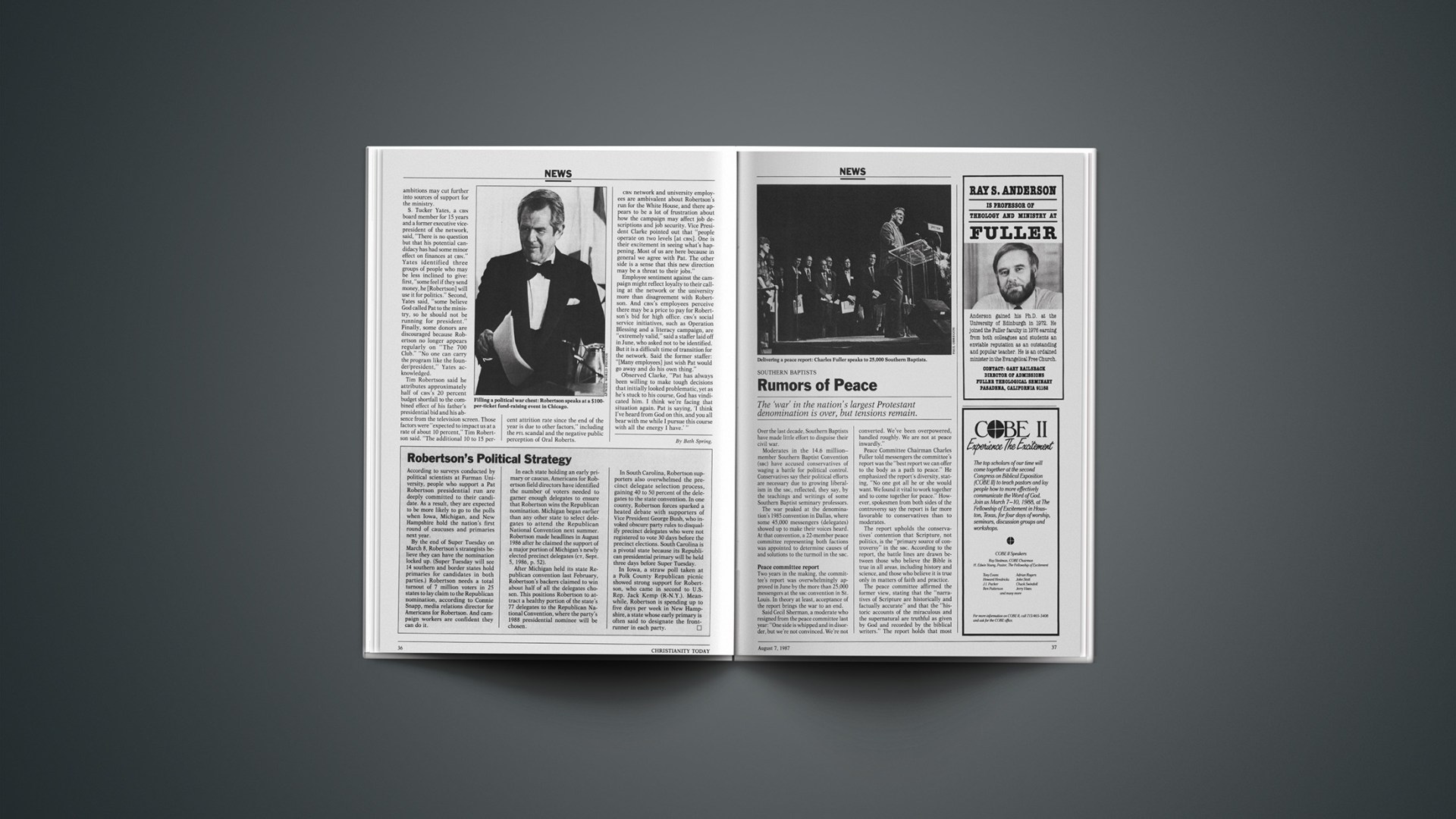

The war peaked at the denomination’s 1985 convention in Dallas, where some 45,000 messengers (delegates) showed up to make their voices heard. At that convention, a 22-member peace committee representing both factions was appointed to determine causes of and solutions to the turmoil in the SBC.

Peace Committee Report

Two years in the making, the committee’s report was overwhelmingly approved in June by the more than 25,000 messengers at the SBC convention in St. Louis. In theory at least, acceptance of the report brings the war to an end.

Said Cecil Sherman, a moderate who resigned from the peace committee last year: “One side is whipped and in disorder, but we’re not convinced. We’re not converted. We’ve been overpowered, handled roughly. We are not at peace inwardly.”

Peace Committee Chairman Charles Fuller told messengers the committee’s report was the “best report we can offer to the body as a path to peace.” He emphasized the report’s diversity, stating, “No one got all he or she would want. We found it vital to work together and to come together for peace.” However, spokesmen from both sides of the controversy say the report is far more favorable to conservatives than to moderates.

The report upholds the conservatives’ contention that Scripture, not politics, is the “primary source of controversy” in the SBC. According to the report, the battle lines are drawn between those who believe the Bible is true in all areas, including history and science, and those who believe it is true only in matters of faith and practice.

The peace committee affirmed the former view, stating that the “narratives of Scripture are historically and factually accurate” and that the “historic accounts of the miraculous and the supernatural are truthful as given by God and recorded by the biblical writers.” The report holds that most Southern Baptists believe Adam and Eve “were real persons” and that the “named authors did indeed write the biblical books attributed to them by those books.”

Although the report maintains that diversity in the SBC “should not create hostility … [or] stand in the way of genuine cooperation,” moderate leaders spoke of defeat and exile within their own denomination. “You have been disenfranchised,” said James Slatton, addressing his moderate colleagues. Slatton, the recognized leader of SBC moderates, said acceptance of the report represents a fundamental change in the SBC, from unity based on a common task (evangelizing the world) to an attempt at unity based on a creed (the inerrancy of Scripture).

Sherman predicted that those with a moderate point of view will now “go into a sullen quiet.… [The] people we have defended no longer care to be defended.” He said he was referring to SBC seminary presidents, who he believes have caved in to conservative pressure.

Moderate Winfred Moore resigned from the peace committee shortly after its report was adopted. He said he objected to the report’s recommendation that the committee’s life be extended up to three years to “observe response.” Moore expressed concern that the panel would become a “police committee” to “monitor or judge the work of our institutions and agencies.…”

The report’s critics are concerned primarily about the recommendation that trustees “determine the theological positions of the seminary administrators and faculty members” in order to “guide them in renewing their determination to [uphold Southern Baptist beliefs].” Some feel this is a call for ruthless housecleaning. But SBC President Adrian Rogers, elected to a third term at the St. Louis convention, said conservative leadership “does not have a firing mentality.”

Presidential Election

Another indication of the conservatives’ victory was the relative ease (by a 60-to 40-percent margin) with which Rogers, a conservative incumbent, won the SBC presidency. This marked the ninth consecutive win for conservatives. The SBC president has substantial power to determine who controls the SBC’S 24 national entities, including its seminaries.

Moderates allege that Rogers has exercised his appointive powers to favor those who share his view of inerrancy. However, stating that conservatives “are not interested in forcing our views” on anyone, Rogers said his appointments “represent who Southern Baptists are.” According to Rogers, the landmark 1963 Baptist Faith and Message statement upholds Scripture as inerrant in all areas. “I could not hold my head up as president of the Southern Baptist Convention,” he said, “if I were to nominate anybody outside that statement.”

Slatton said that for moderate presidential candidate Richard Jackson to have received 40 percent of the vote in a year when there is “discouragement in the ranks” indicates the moderate wing is more substantial than conservatives claim. Slatton maintains also that attendance at recent SBC yearly meetings has not accurately represented the conservative-moderate balance in the denomination. According to research by an independent group, Slatton said, more Southern Baptists would rather be called “liberal,” “progressive,” or “moderate,” than “conservative” or “fundamentalist.”

Other Actions

Other highlights of this year’s SBC meeting include the following:

• Messengers passed 15 resolutions, including one on integrity in stewardship that deplores the recent “tragic revelations of embarrassing misconduct” and mishandling of funds. Although three Southern Baptists now serve on PTL’S reorganized board, the resolution notes that the scandal-plagued ministry is not connected to the SBC.

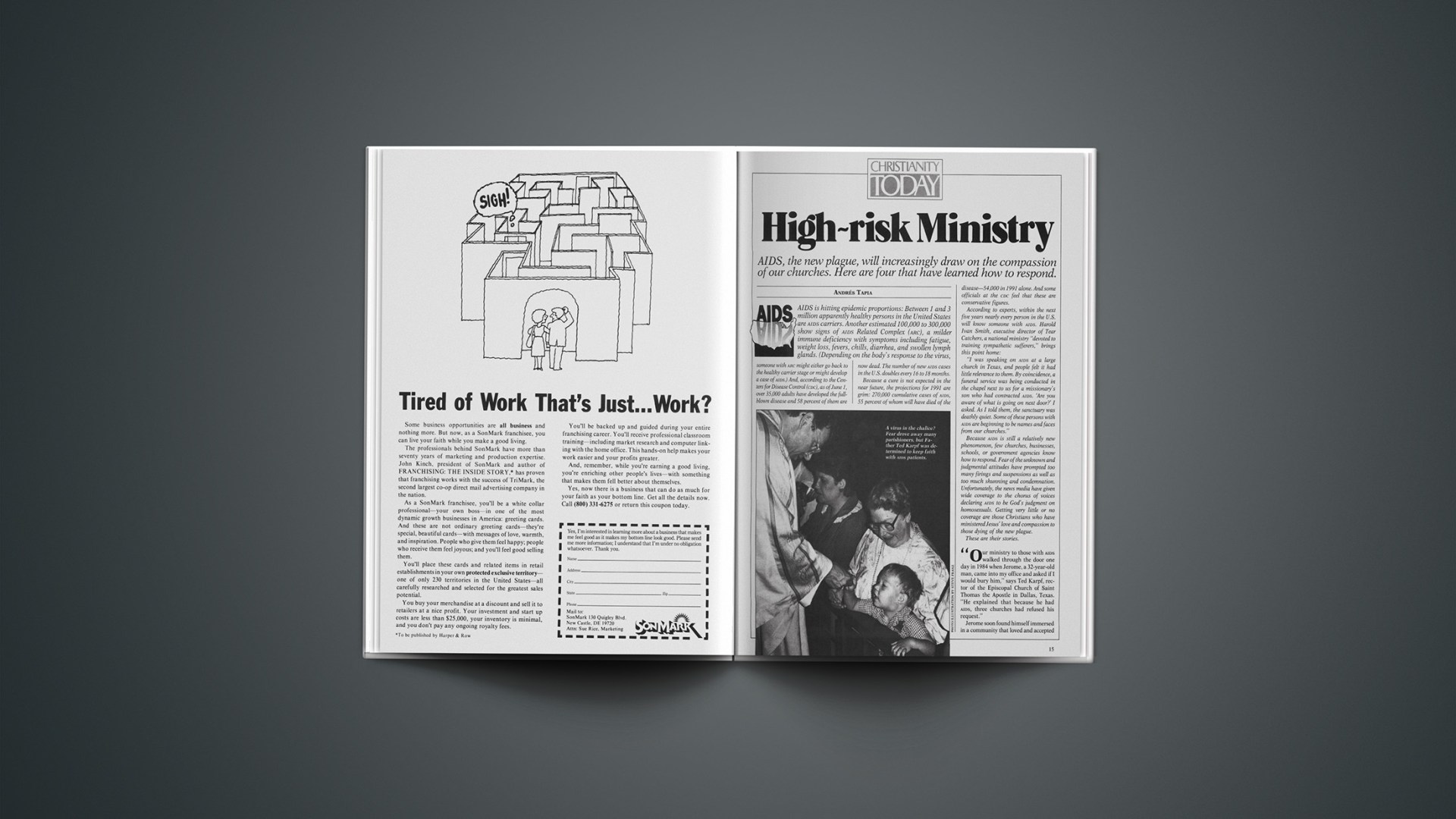

Messengers also passed resolutions making ministry to homeless children a priority, affirming “full-time homemakers,” and calling for obedience to “God’s laws of chastity” as a “major step toward curtailing the threat of AIDS.” The AIDS resolution urges “Christlike compassion in dealing with the hurting victims of AIDS and their families.”

• Former SBC president Jimmy Draper, along with Southern Baptist laymen Ed McAteer and Sam Moore, hosted a reception for presidential hopeful Pat Robertson. The meeting was apparently held to break down barriers that may be limiting Southern Baptist support for Robertson (see related story on p. 34).

• Evangelist Bailey Smith made no apologies for the remark he made in 1980 while SBC president that God does not hear the prayers of Jews. In a speech to Southern Baptist evangelists, Smith said he loves the Jewish people, but that “unless they repent and get born again, they are in trouble.”

By Randy Frame, in St. Louis.

CANADA

Saying No To The Death Penalty

A decisive vote in Canada’s House of Commons against restoring the death penalty has led a Christian leader to call for reforming the entire criminal justice system.

“Now that the capital punishment debate is behind us,” said Ian Stanley, executive director of Prison Fellowship Canada, “Parliament must give attention to the really urgent business of overhaul of the whole criminal justice system.

“The recent debate [over capital punishment] was precipitated by general dissatisfaction with the way the system works,” Stanley said. “It is imperative that Christians come forward with positive proposals.”

A coalition of mainline Protestant and Catholic church leaders figured prominently in the effort opposing capital punishment. However, among evangelicals, only 24 percent opposed imposition of the death penalty under any circumstances, according to a poll published by Faith Today magazine. The remaining 76 percent supported the death penalty—some with qualifications.

Capital punishment has been a festering issue since 1976 when it was abolished by Canada’s Parliament. Although polls indicated widespread public support for reinstating the death penalty, politicians resisted attempts to raise the issue in Parliament.

During the 1984 election campaign, however, Progressive Conservative leader Brian Mulroney promised that, if elected, he would put the issue to a vote in the House of Commons. Although Mulroney said he was personally opposed to capital punishment, in February he permitted the introduction of a motion that would have reinstated the death penalty. When a vote was taken earlier this summer, legislators rejected the motion 148 to 127.

By Leslie K. Tarr.