Author Jeffrey K. Hadden is a professor of sociology at the University of Virginia. He is co-author of Prime Time Preachers (Addison-Wesley), and he is completing work on a second book about the electronic church.

Ever since Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority burst upon the national scene in 1980, a mythology of impending doom has emerged regarding the fate of those who would mix conservative politics and Christian faith. In 1983, National Public Radio reporter Tina Rosenberg argued in The Washington Monthly that Falwell was merely a media creation.

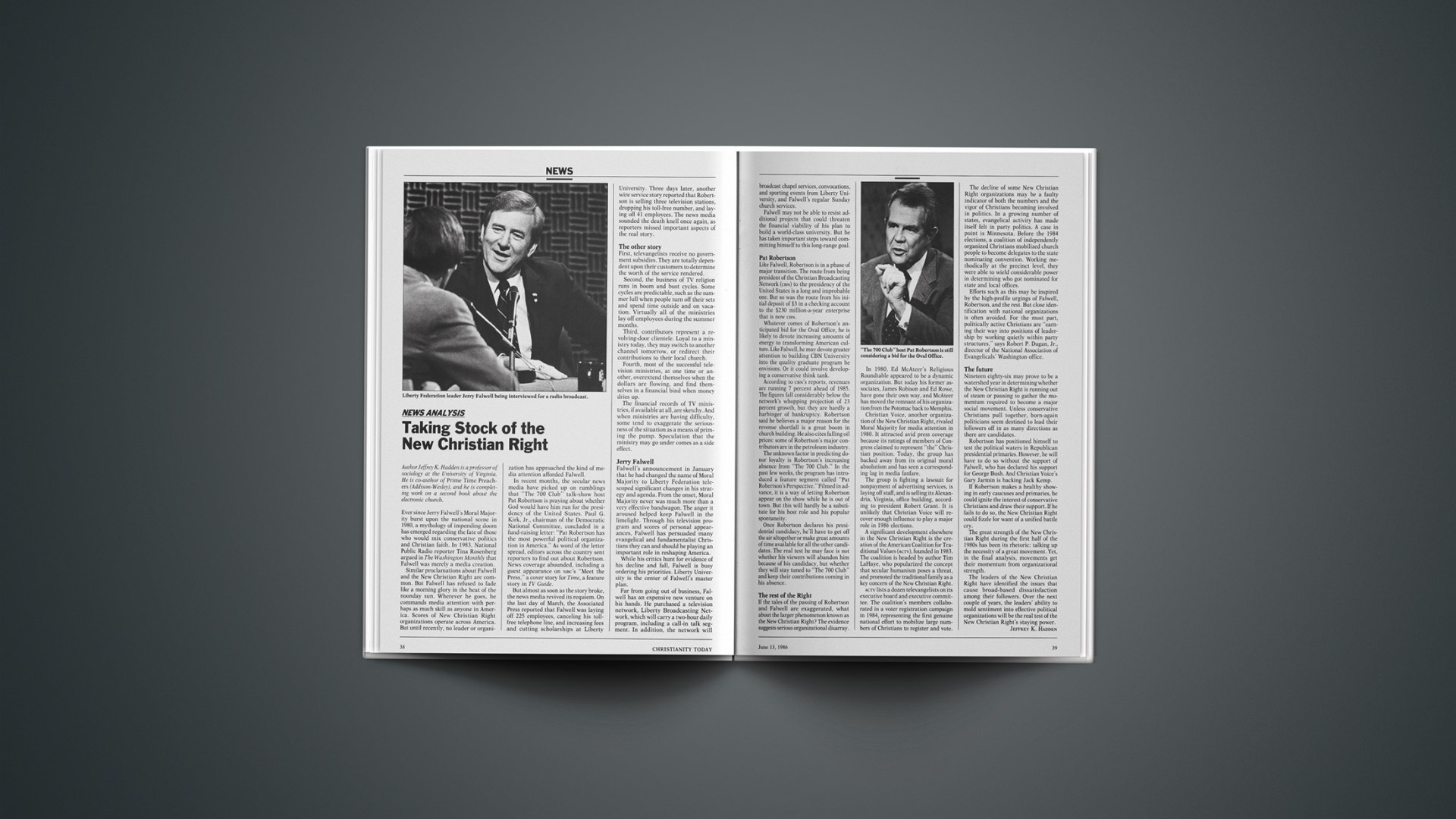

Similar proclamations about Falwell and the New Christian Right are common. But Falwell has refused to fade like a morning glory in the heat of the noonday sun. Wherever he goes, he commands media attention with perhaps as much skill as anyone in America. Scores of New Christian Right organizations operate across America. But until recently, no leader or organization has approached the kind of media attention afforded Falwell.

In recent months, the secular news media have picked up on rumblings that “The 700 Club” talk-show host Pat Robertson is praying about whether God would have him run for the presidency of the United States. Paul G. Kirk, Jr., chairman of the Democratic National Committee, concluded in a fund-raising letter: “Pat Robertson has the most powerful political organization in America.” As word of the letter spread, editors across the country sent reporters to find out about Robertson. News coverage abounded, including a guest appearance on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” a cover story for Time, a feature story in TV Guide.

But almost as soon as the story broke, the news media revived its requiem. On the last day of March, the Associated Press reported that Falwell was laying off 225 employees, canceling his toll-free telephone line, and increasing fees and cutting scholarships at Liberty University. Three days later, another wire service story reported that Robertson is selling three television stations, dropping his toll-free number, and laying off 41 employees. The news media sounded the death knell once again, as reporters missed important aspects of the real story.

The Other Story

First, televangelists receive no government subsidies. They are totally dependent upon their customers to determine the worth of the service rendered.

Second, the business of TV religion runs in boom and bust cycles. Some cycles are predictable, such as the summer lull when people turn off their sets and spend time outside and on vacation. Virtually all of the ministries lay off employees during the summer months.

Third, contributors represent a revolving-door clientele. Loyal to a ministry today, they may switch to another channel tomorrow, or redirect their contributions to their local church.

Fourth, most of the successful television ministries, at one time or another, overextend themselves when the dollars are flowing, and find themselves in a financial bind when money dries up.

The financial records of TV ministries, if available at all, are sketchy. And when ministries are having difficulty, some tend to exaggerate the seriousness of the situation as a means of priming the pump. Speculation that the ministry may go under comes as a side effect.

Jerry Falwell

Falwell’s announcement in January that he had changed the name of Moral Majority to Liberty Federation telescoped significant changes in his strategy and agenda. From the onset, Moral Majority never was much more than a very effective bandwagon. The anger it aroused helped keep Falwell in the limelight. Through his television program and scores of personal appearances, Falwell has persuaded many evangelical and fundamentalist Christians they can and should be playing an important role in reshaping America.

While his critics hunt for evidence of his decline and fall, Falwell is busy ordering his priorities. Liberty University is the center of Falwell’s master plan.

Far from going out of business, Falwell has an expensive new venture on his hands. He purchased a television network, Liberty Broadcasting Network, which will carry a two-hour daily program, including a call-in talk segment. In addition, the network will broadcast chapel services, convocations, and sporting events from Liberty University, and Falwell’s regular Sunday church services.

Falwell may not be able to resist additional projects that could threaten the financial viability of his plan to build a world-class university. But he has taken important steps toward committing himself to this long-range goal.

Pat Robertson

Like Falwell, Robertson is in a phase of major transition. The route from being president of the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) to the presidency of the United States is a long and improbable one. But so was the route from his initial deposit of $3 in a checking account to the $230 million-a-year enterprise that is now CBN.

Whatever comes of Robertson’s anticipated bid for the Oval Office, he is likely to devote increasing amounts of energy to transforming American culture. Like Falwell, he may devote greater attention to building CBN University into the quality graduate program he envisions. Or it could involve developing a conservative think tank.

According to CBN’s reports, revenues are running 7 percent ahead of 1985. The figures fall considerably below the network’s whopping projection of 23 percent growth, but they are hardly a harbinger of bankruptcy. Robertson said he believes a major reason for the revenue shortfall is a great boom in church building. He also cites falling oil prices: some of Robertson’s major contributors are in the petroleum industry.

The unknown factor in predicting donor loyalty is Robertson’s increasing absence from “The 700 Club.” In the past few weeks, the program has introduced a feature segment called “Pat Robertson’s Perspective.” Filmed in advance, it is a way of letting Robertson appear on the show while he is out of town. But this will hardly be a substitute for his host role and his popular spontaneity.

Once Robertson declares his presidential candidacy, he’ll have to get off the air altogether or make great amounts of time available for all the other candidates. The real test he may face is not whether his viewers will abandon him because of his candidacy, but whether they will stay tuned to “The 700 Club” and keep their contributions coming in his absence.

The Rest Of The Right

If the tales of the passing of Robertson and Falwell are exaggerated, what about the larger phenomenon known as the New Christian Right? The evidence suggests serious organizational disarray.

In 1980, Ed McAteer’s Religious Roundtable appeared to be a dynamic organization. But today his former associates, James Robison and Ed Rowe, have gone their own way, and McAteer has moved the remnant of his organization from the Potomac back to Memphis.

Christian Voice, another organization of the New Christian Right, rivaled Moral Majority for media attention in 1980. It attracted avid press coverage because its ratings of members of Congress claimed to represent “the” Christian position. Today, the group has backed away from its original moral absolutism and has seen a corresponding lag in media fanfare.

The group is fighting a lawsuit for nonpayment of advertising services, is laying off staff, and is selling its Alexandria, Virginia, office building, according to president Robert Grant. It is unlikely that Christian Voice will recover enough influence to play a major role in 1986 elections.

A significant development elsewhere in the New Christian Right is the creation of the American Coalition for Traditional Values (ACTV), founded in 1983. The coalition is headed by author Tim LaHaye, who popularized the concept that secular humanism poses a threat, and promoted the traditional family as a key concern of the New Christian Right.

ACTV lists a dozen televangelists on its executive board and executive committee. The coalition’s members collaborated in a voter registration campaign in 1984, representing the first genuine national effort to mobilize large numbers of Christians to register and vote.

The decline of some New Christian Right organizations may be a faulty indicator of both the numbers and the vigor of Christians becoming involved in politics. In a growing number of states, evangelical activity has made itself felt in party politics. A case in point is Minnesota. Before the 1984 elections, a coalition of independently organized Christians mobilized church people to become delegates to the state nominating convention. Working methodically at the precinct level, they were able to wield considerable power in determining who got nominated for state and local offices.

Efforts such as this may be inspired by the high-profile urgings of Falwell, Robertson, and the rest. But close identification with national organizations is often avoided. For the most part, politically active Christians are “earning their way into positions of leadership by working quietly within party structures,” says Robert P. Dugan, Jr., director of the National Association of Evangelicals’ Washington office.

The Future

Nineteen eighty-six may prove to be a watershed year in determining whether the New Christian Right is running out of steam or pausing to gather the momentum required to become a major social movement. Unless conservative Christians pull together, born-again politicians seem destined to lead their followers off in as many directions as there are candidates.

Robertson has positioned himself to test the political waters in Republican presidential primaries. However, he will have to do so without the support of Falwell, who has declared his support for George Bush. And Christian Voice’s Gary Jarmin is backing Jack Kemp.

If Robertson makes a healthy showing in early caucuses and primaries, he could ignite the interest of conservative Christians and draw their support. If he fails to do so, the New Christian Right could fizzle for want of a unified battle cry.

The great strength of the New Christian Right during the first half of the 1980s has been its rhetoric: talking up the necessity of a great movement. Yet, in the final analysis, movements get their momentum from organizational strength.

The leaders of the New Christian Right have identified the issues that cause broad-based dissatisfaction among their followers. Over the next couple of years, the leaders’ ability to mold sentiment into effective political organizations will be the real test of the New Christian Right’s staying power.

JEFFREY K. HADDEN