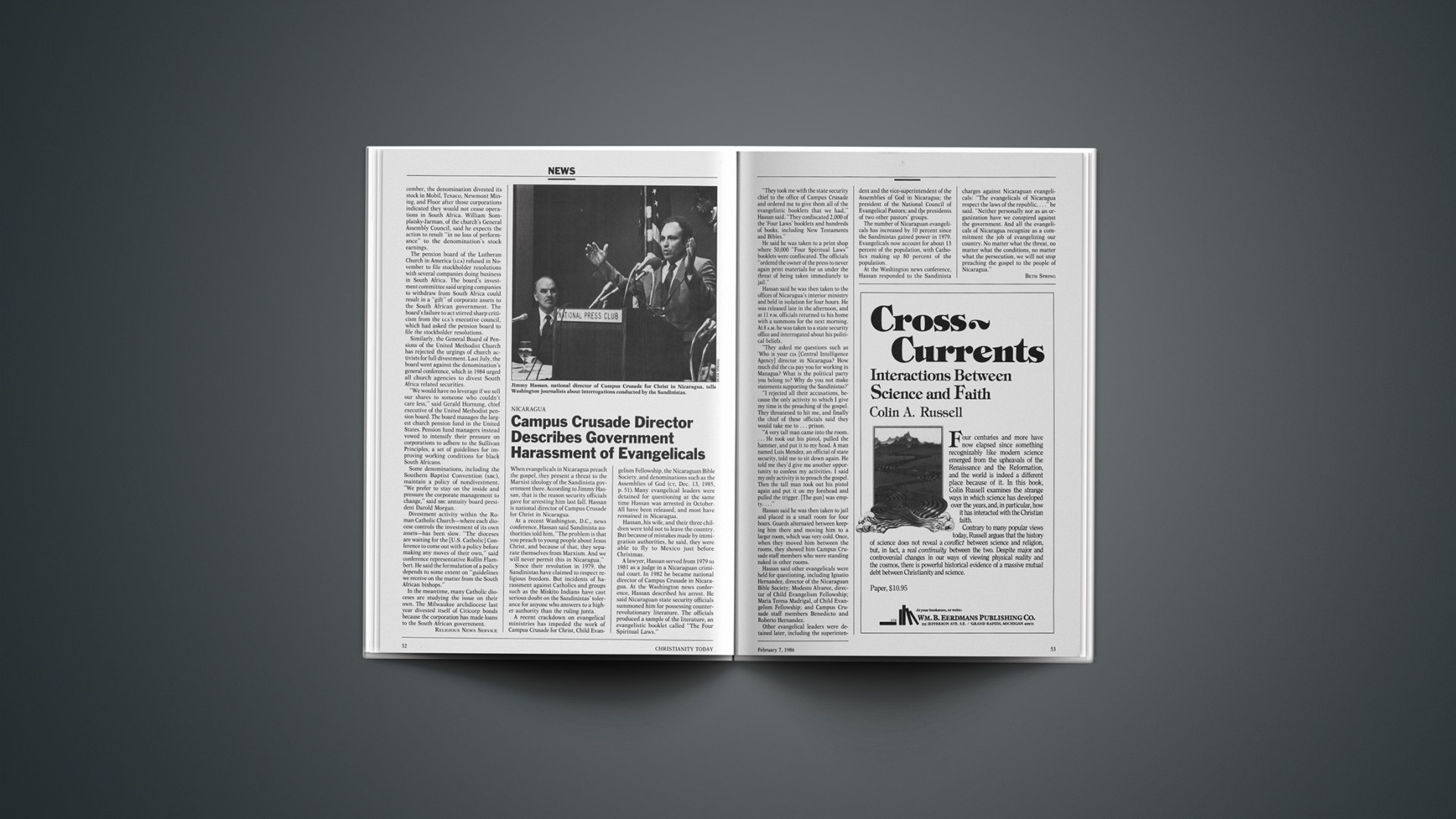

When evangelicals in Nicaragua preach the gospel, they present a threat to the Marxist ideology of the Sandinista government there. According to Jimmy Hassan, that is the reason security officials gave for arresting him last fall. Hassan is national director of Campus Crusade for Christ in Nicaragua.

At a recent Washington, D.C., news conference, Hassan said Sandinista authorities told him, “The problem is that you preach to young people about Jesus Christ, and because of that, they separate themselves from Marxism. And we will never permit this in Nicaragua.”

Since their revolution in 1979, the Sandinistas have claimed to respect religious freedom. But incidents of harassment against Catholics and groups such as the Miskito Indians have cast serious doubt on the Sandinistas’ tolerance for anyone who answers to a higher authority than the ruling junta.

A recent crackdown on evangelical ministries has impeded the work of Campus Crusade for Christ, Child Evangelism Fellowship, the Nicaraguan Bible Society, and denominations such as the Assemblies of God (CT, Dec. 13, 1985, p. 51). Many evangelical leaders were detained for questioning at the same time Hassan was arrested in October. All have been released, and most have remained in Nicaragua.

Hassan, his wife, and their three children were told not to leave the country. But because of mistakes made by immigration authorities, he said, they were able to fly to Mexico just before Christmas.

A lawyer, Hassan served from 1979 to 1981 as a judge in a Nicaraguan criminal court. In 1982 he became national director of Campus Crusade in Nicaragua. At the Washington news conference, Hassan described his arrest. He said Nicaraguan state security officials summoned him for possessing counter-revolutionary literature. The officials produced a sample of the literature, an evangelistic booklet called “The Four Spiritual Laws.”

“They took me with the state security chief to the office of Campus Crusade and ordered me to give them all of the evangelistic booklets that we had,” Hassan said. “They confiscated 2,000 of the ‘Four Laws’ booklets and hundreds of books, including New Testaments and Bibles.”

He said he was taken to a print shop where 50,000 “Four Spiritual Laws” booklets were confiscated. The officials “ordered the owner of the press to never again print materials for us under the threat of being taken immediately to jail.”

Hassan said he was then taken to the offices of Nicaragua’s interior ministry and held in isolation for four hours. He was released late in the afternoon, and at 11 P.M. officials returned to his home with a summons for the next morning. At 8 A.M. he was taken to a state security office and interrogated about his political beliefs.

“They asked me questions such as ‘Who is your CIA [Central Intelligence Agency] director in Nicaragua? How much did the CIA pay you for working in Managua? What is the political party you belong to? Why do you not make statements supporting the Sandinistas?’

“I rejected all their accusations, because the only activity to which I give my time is the preaching of the gospel. They threatened to hit me, and finally the chief of these officials said they would take me to … prison.

“A very tall man came into the room.… He took out his pistol, pulled the hammer, and put it to my head. A man named Luis Mendez, an official of state security, told me to sit down again. He told me they’d give me another opportunity to confess my activities. I said my only activity is to preach the gospel. Then the tall man took out his pistol again and put it on my forehead and pulled the trigger. [The gun] was empty.…”

Hassan said he was then taken to jail and placed in a small room for four hours. Guards alternated between keeping him there and moving him to a larger room, which was very cold. Once, when they moved him between the rooms, they showed him Campus Crusade staff members who were standing naked in other rooms.

Hassan said other evangelicals were held for questioning, including Ignatio Hernandez, director of the Nicaraguan Bible Society; Modesto Alvarez, director of Child Evangelism Fellowship; Maria Teresa Madrigal, of Child Evangelism Fellowship; and Campus Crusade staff members Benedicto and Roberto Hernandez.

Other evangelical leaders were detained later, including the superintend dent and the vice-superintendent of the Assemblies of God in Nicaragua; the president of the National Council of Evangelical Pastors; and the presidents of two other pastors’ groups.

The number of Nicaraguan evangelicals has increased by 10 percent since the Sandinistas gained power in 1979. Evangelicals now account for about 13 percent of the population, with Catholics making up 80 percent of the population.

At the Washington news conference, Hassan responded to the Sandinista charges against Nicaraguan evangelicals: “The evangelicals of Nicaragua respect the laws of the republic, …” he said. “Neither personally nor as an organization have we conspired against the government. And all the evangelicals of Nicaragua recognize as a commitment the job of evangelizing our country. No matter what the threat, no matter what the conditions, no matter what the persecution, we will not stop preaching the gospel to the people of Nicaragua.”

WORLD SCENE

INDIA

Mobilizing Missionaries

At a recent missions conference in southern India, participants heard native evangelists from northern India describe beatings they received for preaching the gospel. Still, some 300 pastors and evangelists from the southern state of Kerala volunteered to do pioneer mission work in northern India. Some 800 other pastors pledged to recruit at least one missionary from each of their congregations.

Sponsored by Gospel for Asia, the conference challenged participants to do mission work in northern states where Hindus and Muslims predominate. The 300 volunteers will leave the southern state of Kerala, which is 30 percent Christian in a nation that is 90 percent Hindu.

K. P. Yohannan, president of Gospel for Asia, called the churches in Kerala “the sleeping giant of India.” In the past, young people from Kerala made up a significant portion of the street evangelists working in the northern part of the country. However, Yohannan said, many of Kerala’s young people are accepting jobs in the oil-rich nations of the Middle East, preventing them from doing mission work in northern India.

SOVIET UNION

Crackdown on Alcohol Abuse

The Soviet Union’s Supreme Court has announced a series of penalties for alcohol abuse, making several acts criminal offenses for the first time.

Selling or giving alcohol to minors, illegal brewing, and drinking outdoors will be punished, although specific sentences were not made public. In addition, the court said the state may take children of alcoholics into compulsory care.

The new measures are seen as part of an intensified effort by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to clamp down on alcohol abuse. The newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda reported that two members of the Young Communist League’s central committee were dismissed for excessive drinking and other offenses. Soviet citizens consume an average of 30 liters of vodka annually.

CHINA

A Catholic Church Reopened

China’s Patriotic Catholic Association has restored and reopened a nineteenth-century church in Peking that can hold 3,000 people. It was the third Catholic church to be reopened in the capital since 1976. An estimated 30,000 Catholics live in Peking.

City officials approved $300,000 for the reconstruction of the Church of the Savior. Closed since the 1950s, the church was used as a warehouse by Maoist Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution, a period during which Chinese Christians suffered severe persecution.

Some observers say the government is relaxing its attitude toward Catholics. Vatican radio said 51 Catholic churches recently were reopened in China’s Fujian Province alone.

However, China continues to crack down on priests and parishioners suspected of maintaining ties with Rome. The Chinese Catholic Church broke with the Vatican in 1957 under government pressure. The church ordains its own bishops and priests, and still follows pre-Vatican II practices, including the celebration of Mass in Latin. The Chinese government’s Religious Affairs Bureau estimates there are as many as three million Catholics in the country.

WEST GERMANY

Cult Hotline

The Catholic archdiocese in Cologne, West Germany, has set up a telephone hotline to help family members and friends of those influenced by new religious sects. An estimated 30 cults are represented in the city.

Callers often complain that a friend or family member has broken off contact with them after becoming interested in a cult. “We try to get rid of exaggerated fears while at the same time explaining how the sects operate, so that the relatives and friends have some idea of what they’re dealing with,” said a 27-year-old hotline worker.

Followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, the Indian guru who last year left the United States, have their European headquarters in Cologne. Another cult in the city is reviving worship of pre-Christian Germanic gods. Experts say 80 percent of the cults in Cologne have established bases there in the past ten years.

Wener Hoebsch, cult specialist for the Cologne archdiocese, says established churches have not made themselves attractive to those who grew up without a close church connection. He said it is those people who are attracted to the new religious sects.

AFRICA

Improved Food Outlook

A United Nations official says improved harvests in several African countries have given the continent enough food to feed itself this year.

Bradford Morse, director of the Office for Emergency Operations in Africa, said relief agencies will need more than $500 million to buy that food and transport it to the 19 million Africans still facing starvation. If donor countries contribute grain instead of cash, he said, African farmers will be unable to sell their harvests, weakening their incentive to grow more food.

“There is enough food in Africa to feed Africa,” Morse said. “It would be nonsensical to ship food when food is already available there.” In all, Morse said African countries will need more than $ 1 billion in drought-related assistance this year, compared to $2.9 billion in 1985.

Emergency conditions remain in 6 of the 20 countries affected by the drought, Morse said. Eight other countries still need immediate help. Some countries, like the Sudan, are agriculturally self-sufficient, but they are unable to buy and ship food to devastated regions. The Sudan, Angola, Botswana, Cape Verde, Ethiopia, and Mozambique still face mass starvation. Three million Africans are homeless as a result of the famine.