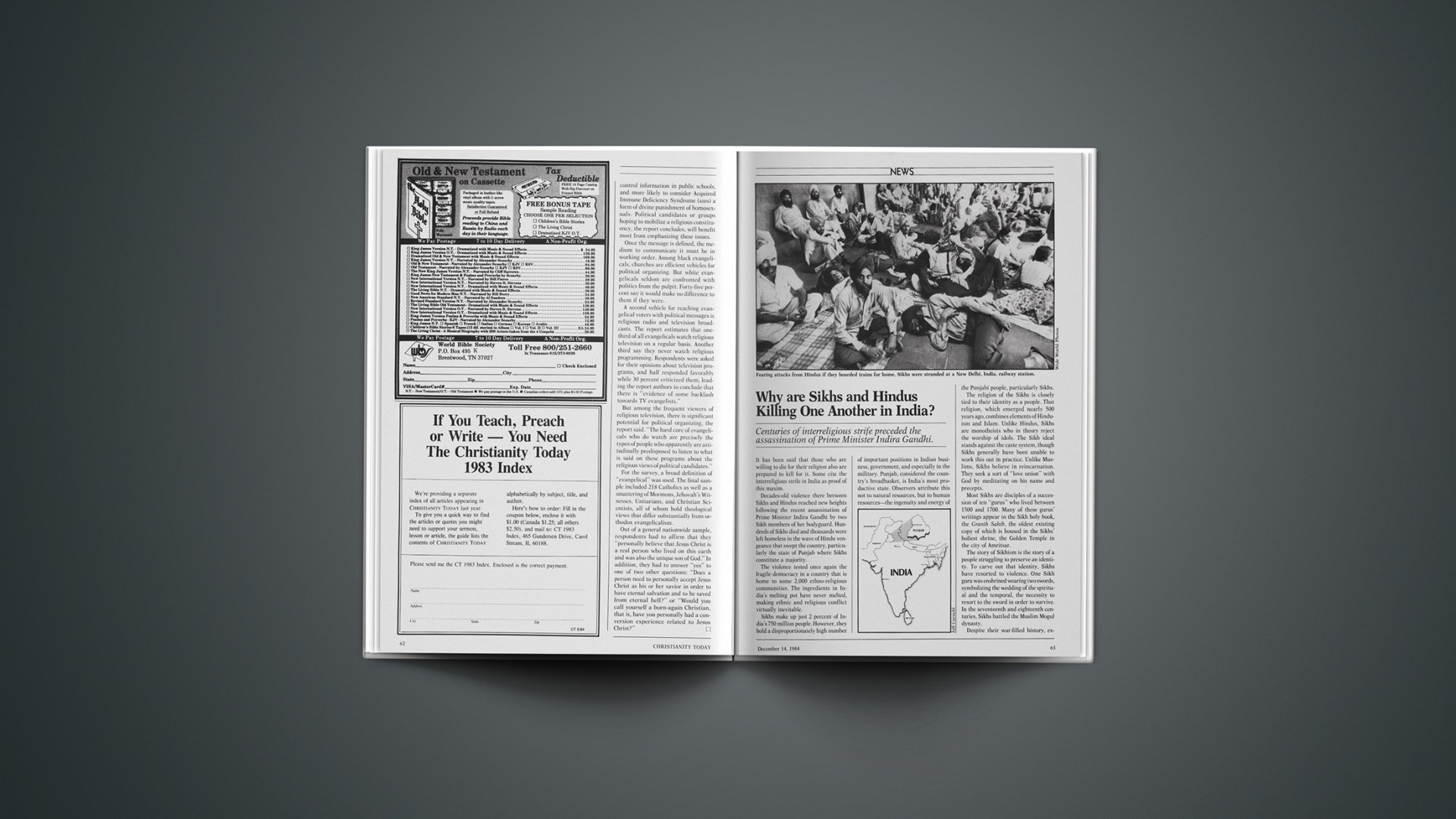

Centuries of interreligious strife preceded the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

It has been said that those who are willing to die for their religion also are prepared to kill for it. Some cite the interreligious strife in India as proof of this maxim.

Decades-old violence there between Sikhs and Hindus reached new heights following the recent assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by two Sikh members of her bodyguard. Hundreds of Sikhs died and thousands were left homeless in the wave of Hindu vengeance that swept the country, particularly the state of Punjab where Sikhs constitute a majority.

The violence tested once again the fragile democracy in a country that is home to some 2,000 ethno-religious communities. The ingredients in India’s melting pot have never melted, making ethnic and religious conflict virtually inevitable.

Sikhs make up just 2 percent of India’s 750 million people. However, they hold a disproportionately high number of important positions in Indian business, government, and especially in the military. Punjab, considered the country’s breadbasket, is India’s most productive state. Observers attribute this not to natural resources, but to human resources—the ingenuity and energy of the Punjabi people, particularly Sikhs.

The religion of the Sikhs is closely tied to their identity as a people. That religion, which emerged nearly 500 years ago, combines elements of Hinduism and Islam. Unlike Hindus, Sikhs are monotheists who in theory reject the worship of idols. The Sikh ideal stands against the caste system, though Sikhs generally have been unable to work this out in practice. Unlike Muslims, Sikhs believe in reincarnation. They seek a sort of “love union” with God by meditating on his name and precepts.

Most Sikhs are disciples of a succession of ten “gurus” who lived between 1500 and 1700. Many of these gurus’ writings appear in the Sikh holy book, the Granth Sahib, the oldest existing copy of which is housed in the Sikhs’ holiest shrine, the Golden Temple in the city of Amritsar.

The story of Sikhism is the story of a people struggling to preserve an identity. To carve out that identity, Sikhs have resorted to violence. One Sikh guru was enshrined wearing two swords, symbolizing the wedding of the spiritual and the temporal, the necessity to resort to the sword in order to survive. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Sikhs battled the Muslim Mogul dynasty.

Despite their war-filled history, experts say the perception that Sikhs are attracted to violence is unjustified. “It’s been confused in people’s minds that all Sikhs are terrorists,” said India scholar Paul Wallace of the University of Missouri. “The overwhelming majority of Sikhs are nonviolent.”

University of Wisconsin professor Robert Frykenberg, born and reared in India as a son of Christian missionaries, said the American news media is partially responsible for the misperception. “To show Sikhs dancing in the streets [celebrating Indira Gandhi’s death] without pointing out the huge moderate block which does not hold to the extremists’ views was inflammatory and irresponsible,” he said. “It probably led to further bloodshed because the reports were shown almost immediately on Indian TV.”

The Sikh identity was dealt a severe blow in 1947. With the partitioning of the Punjab region, western Punjab, the cradle of Sikh culture, became a part of Muslim Pakistan. The eastern Punjab remained Hindu. Three years later, the Indian constitution defined Sikhism not as a distinct religion, but as a Hindu sect. Since then, things have improved for the Sikhs. Frykenberg cited the recent violence as evidence of the improvement. “People become restive when circumstances get better and then something comes along to frustrate the progress.”

Sikhs made moderate advances in the first half of the twentieth century under British rule. Progress continued from 1947 to 1964 when Indira Gandhi’s father, Jawaharlal Nehru, ruled India. In 1966, eastern Punjab was broken into two states. The northern portion retained the name Punjab, and the Sikhs at long last had a state in which they constituted a political majority.

But Wallace said that under Gandhi, the sensitivity that Nehru displayed was “significantly qualified.” Frykenberg added that Gandhi sparked unrest by “systematically destabilizing anyone who opposed her.”

Most observers, including Wallace and Frykenberg, said Gandhi and her Congress-I party intentionally encouraged Sikh extremists in order to pit Sikh against Sikh, thus undercutting Sikh political unity. But in doing so, Wallace said, “they created Frankenstein.”

He said one of the side effects of Gandhi’s interference was the emergence of an influential terrorist leader named Jamail Singh Bhindranwale. Two years ago, Bhindranwale led some 1,000 Sikh terrorists into the Golden Temple at Amritsar. From there, they launched terrorist attacks, killing hundreds of Hindus. Finally, last June, the Indian army moved in with heavy artillery, annihilating the terrorists and defacing some of the buildings on the grounds of the Sikhs’ holy shrine.

This act of aggression enraged even moderate Sikhs, including, in all probability, the two men who later killed Gandhi. Frykenberg said one of the assassins grew up in the same area as Bhindranwale, and quite likely knew his family.

The violence has opened a window of opportunity for India’s small Christian community. “The idea of Eastern religions being peaceful and tolerant has been shatterred,” said Paul Hiebert, professor of missions anthropolgy at Fuller Theological Seminary. Hiebert, who, like Frykenberg, grew up on India’s mission field, said Indian citizens regard Christianity as a religion of war. “They refer to the atom bomb as the ‘Christian bomb,’ ” he said.

“Christians now have the opportunity to reverse that. Among people in the East, peace is not just on the agenda, peace is the agenda for spirituality,” Hiebert said. “If Christianity can be seen as a religion of peace, Christians can have a tremendous impact throughout the region.”

North American Scene

The United Methodist Church’s highest court has upheld a ban on the ordination of “self-avowed, practicing homosexuals.” The ban was passed by the denomination’s general conference in May. However, the church court restricted the authority of Methodist bishops to refuse ministerial appointments to already-ordained homosexuals. A bishop can take such action only if a regional church body already has suspended an ordained homosexual.

The trustees of two Christian liberal arts colleges in the Northeast have voted to merge the institutions. Gordon College, near Boston, and Barrington College, near Providence, Rhode Island, will combine operations beginning with the 1985–86 school year. Barrington’s 110-acre campus will be sold, with the money being used to expand facilities at Gordon’s 900-acre campus (CT, Nov. 9, 1984, p. 66).

The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to decide whether federal aid to parochial schools violates the First Amendment. The case involves New York City’s use of federal funds to send public school teachers into parochial schools to provide specialized instruction. A lower court ruled that the practice violates the First Amendment’s ban on an establishment of religion. However, New York City argues that the practice does not advance religion or excessively entangle government with the church.

Two former Indiana governors and more than 60 religious, educational, and political leaders are combating efforts to legalize gambling in the state. The group plans to finance a lobbying effort to ensure that Indiana will continue to prohibit all forms of gambling, including a state lottery. Mississippi, Utah, and Hawaii are the only other states that outlaw all forms of gambling.

New York’s highest court has ruled that a person can be deemed legally dead when the brain ceases to function, even if heartbeat and breathing are being maintained artificially. With the ruling, New York joins 37 other states that have expanded the traditional definition of death to include the functioning of the brain.

World Scene

An interracial Christian training center for youth has opened near Johannesburg, South Africa. A project of Youth for Christ/Southern Africa, the center offers short-term courses in leadership and the Bible. Young people—both black and white—from southern Africa, Great Britain, New Zealand, and the United States have received training there.

A West German television documentary reported that some 2,500 witches and satanic priests are active in that country. The program said more than 2 million West Germans have paid for “occult services,” including prophecies, curses, and “death rituals.” The program was broadcast despite the objections of the West German Evangelical Alliance. Alliance chairman Fritz Laubach said the documentary should have included “warning words of the Bible” against occult practices.

The Church of England’s controversial bishop of Durham has described the Resurrection as a “conjuring trick with bones.” David Jenkins made the statement during a BBC radio program. The bishop did not explain what he meant by “conjuring trick.” But he repeated his view that Christians do not need to believe in the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection as absolute facts. Jenkins’s liberal views have raised a stir in the Church of England since July when he was consecrated as the church’s fourth most-senior cleric (CT, Sept. 7, 1984, p. 74).

A Nicaraguan Catholic bishop has publicly criticized the Sandinista government, saying it is not sincerely seeking peace and is imposing “new oppressions.” Bishop Pablo Antonio Vega’s language was stronger than that used in the Nicaraguan bishops’ pastoral letter criticizing the government last April. The bishop said Sandinista ideology “promotes and institutionalizes violence.” His statement is expected to increase friction between the government and the church.

Official figures indicate that the Church of England’s membership is once again on the decline after a modest improvement in the early 1980s. However, some question whether clergymen underreport membership to reduce the amount of assessment, based on membership, that parishes pay to the denomination. Official figures show Sunday attendance down by 2.8 percent.

The head of the Jesuit order says he supports the teachings of liberation theology. Jesuit superior general Peter-Hans Kolvenbach says members of his order will continue to assist efforts to achieve social justice in Latin America. The Vatican has criticized liberation theology, saying it relies too heavily on Marxist analysis.