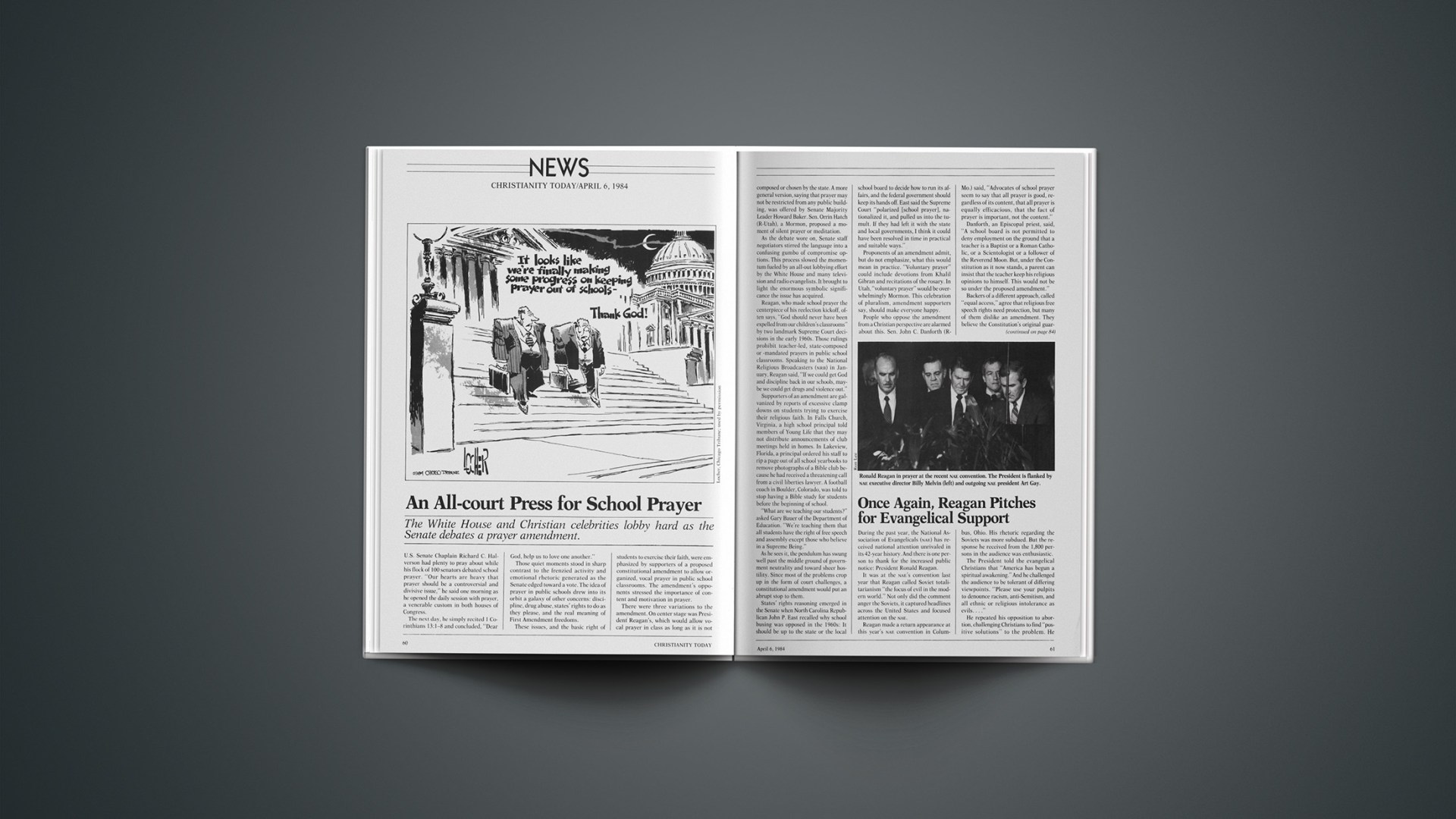

The White House and Christian celebrities lobby hard as the Senate debates a prayer amendment.

U.S. Senate Chaplain Richard C. Halverson had plenty to pray about while his flock of 100 senators debated school prayer. “Our hearts are heavy that prayer should be a controversial and divisive issue,” he said one morning as he opened the daily session with prayer, a venerable custom in both houses of Congress.

The next day, he simply recited 1 Corinthians 13:1–8 and concluded, “Dear God, help us to love one another.”

Those quiet moments stood in sharp contrast to the frenzied activity and emotional rhetoric generated as the Senate edged toward a vote. The idea of prayer in public schools drew into its orbit a galaxy of other concerns: discipline, drug abuse, states’ rights to do as they please, and the real meaning of First Amendment freedoms.

These issues, and the basic right of students to exercise their faith, were emphasized by supporters of a proposed constitutional amendment to allow organized, vocal prayer in public school classrooms. The amendment’s opponents stressed the importance of content and motivation in prayer.

There were three variations to the amendment. On center stage was President Reagan’s, which would allow vocal prayer in class as long as it is not composed or chosen by the state. A more general version, saying that prayer may not be restricted from any public building, was offered by Senate Majority Leader Howard Baker. Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), a Mormon, proposed a moment of silent prayer or meditation.

As the debate wore on, Senate staff negotiators stirred the language into a confusing gumbo of compromise options. This process slowed the momentum fueled by an all-out lobbying effort by the White House and many television and radio evangelists. It brought to light the enormous symbolic significance the issue has acquired.

Reagan, who made school prayer the centerpiece of his reelection kickoff, often says, “God should never have been expelled from our children’s classrooms” by two landmark Supreme Court decisions in the early 1960s. Those rulings prohibit teacher-led, state-composed or -mandated prayers in public school classrooms. Speaking to the National Religious Broadcasters (NRB) in January, Reagan said, “If we could get God and discipline back in our schools, maybe we could get drugs and violence out.”

Supporters of an amendment are galvanized by reports of excessive clamp downs on students trying to exercise their religious faith. In Falls Church, Virginia, a high school principal told members of Young Life that they may not distribute announcements of club meetings held in homes. In Lakeview, Florida, a principal ordered his staff to rip a page out of all school yearbooks to remove photographs of a Bible club because he had received a threatening call from a civil liberties lawyer. A football coach in Boulder, Colorado, was told to stop having a Bible study for students before the beginning of school.

“What are we teaching our students?” asked Gary Bauer of the Department of Education. “We’re teaching them that all students have the right of free speech and assembly except those who believe in a Supreme Being.”

As he sees it, the pendulum has swung well past the middle ground of government neutrality and toward sheer hostility. Since most of the problems crop up in the form of court challenges, a constitutional amendment would put an abrupt stop to them.

States’ rights reasoning emerged in the Senate when North Carolina Republican John P. East recalled why school busing was opposed in the 1960s: It should be up to the state or the local school board to decide how to run its affairs, and the federal government should keep its hands off. East said the Supreme Court “polarized [school prayer], nationalized it, and pulled us into the tumult. If they had left it with the state and local governments, I think it could have been resolved in time in practical and suitable ways.”

Proponents of an amendment admit, but do not emphasize, what this would mean in practice. “Voluntary prayer” could include devotions from Khalil Gibran and recitations of the rosary. In Utah, “voluntary prayer” would be overwhelmingly Mormon. This celebration of pluralism, amendment supporters say, should make everyone happy.

People who oppose the amendment from a Christian perspective are alarmed about this. Sen. John C. Danforth (R-Mo.) said, “Advocates of school prayer seem to say that all prayer is good, regardless of its content, that all prayer is equally efficacious, that the fact of prayer is important, not the content.”

Danforth, an Episcopal priest, said, “A school board is not permitted to deny employment on the ground that a teacher is a Baptist or a Roman Catholic, or a Scientologist or a follower of the Reverend Moon. But, under the Constitution as it now stands, a parent can insist that the teacher keep his religious opinions to himself. This would not be so under the proposed amendment.”

Backers of a different approach, called “equal access,” agree that religious free speech rights need protection, but many of them dislike an amendment. They believe the Constitution’s original guarantees of free exercise of religion are as valid as ever and might be called into question by an amendment that suddenly tacked on school prayer. “The God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Jesus does not need a hall pass in any school,” said Tom Getman, chief legislative aide to Sen. Mark O. Hatfield (R-Oreg.). Hatfield and Sen. Jeremiah Denton (R-Ala.) are sponsoring legislation to permit Bible clubs and off-hour studies on school property.

The President and supporters of his amendment had a difficult time moving Capitol Hill, but they set in motion a mountain of public opinion. Sports figures, including Washington Redskins coach Joe Gibbs and Dallas Cowboys coach Tom Landry, gave personal testimonies before a special House of Representatives hearing. The gridiron rivals sat side by side, and Gibbs described how God permeates every aspect of his family’s life. Redskin place-kicker Mark Moseley believes prayer in school is necessary because “if their family fails them [in religious instruction], school is the only place children will hear about God.

At the same hearing, former football star Rosey Grier quietly described how he had verged on committing suicide at a low point in his life. What kept him from it was his memory of the Lord’s Prayer, recited during grade school. The nuances of the several prayer proposals before Congress seemed unimportant to these advocates. Moseley said he did not prefer any particular measure over another. “All we’re asking is if kids want to pray, schools should allow them to.”

A sweeping Christian media blitz orchestrated by the White House left no doubt about which proposal should steer the bandwagon. Reagan highlighted his prayer amendment in speeches to the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), the NRB, and in a Saturday radio broadcast. Excerpts of the President’s remarks were heard on James Dobson’s “Focus on the Family” radio program and Pat Robertson’s “700 Club.” Administration spokesmen produced editorial page articles on prayer and testified on Capitol Hill.

While House aide James Baker III described the amendment to Dobson’s estimated five million listeners, and overwhelming numbers of them responded with calls to Congress. Sen. Don Nickle (R-Okla.) received 2,000 letters and phone calls in two weeks. “Last year’s abortion vote didn’t receive anywhere near this much attention,” Nickles’s assistant Paul Lee said. “And that one was a lot more clear-cut from a Christian standpoint.”

Dobson’s program mentioned only the President’s amendment. A homemaker in Burke, Virginia, Judi Brotzman, called her two senators after hearing the Dobson show. “I trust him,” she said of Dobson. “I’ve found nothing offensive or off the mark in what he’s said or written. His concerns are for the family and mine are also.” When she placed her calls, she did not know there were other prayer proposals. “I wondered later why Dobson didn’t mention them,” she said.

For his interview with Baker, Dobson was given background material supplied by the White House, including a list of suggested questions. Pebb Jackson, vice-president of Dobson’s organization, said, “We were very aware that there were other amendments, but we knew the President’s amendment included voluntary vocal prayer and prohibited prayers written by the state, and that is what we preferred.” Dobson said, “Not every Christian will see this issue in exactly the same way. Nevertheless, it is my responsibility to speak my own conscience on our radio broadcast and I did that.”

In Hatfield’s office, up to 150 callers each day voiced overwhelming support for an amendment but seemed poorly informed about alternatives. When Getman explained Hatfield’s “equal access legislation” to an Oregon constituent, the caller demanded, “What business does [Hatfield] have introducing a bill?”

According to Getman, many parents changed their minds when they realized their children could be asked to participate in offering prayers outside the Christian tradition. “I’d rather have my daughter compose her own prayer in her head,” one mother acknowledged.

The debate has had noticeable effect on some Senate staff members. Paul Lee said, “People are beginning to ask themselves, ‘Do I pray? How important is this to me? What is my relationship with God?’ ”

From Halverson’s perspective, the time and energy invested by senators on both sides of the issue was impressive. “It ought to mean something to the nation that this powerful legislative body is taking prayer so seriously.”

Once Again, Reagan Pitches For Evangelical Support

During the past year, the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) has received national attention unrivaled in its 42-year history. And there is one person to thank for the increased public notice: President Ronald Reagan.

It was at the NAE’s convention last year that Reagan called Soviet totalitarianism “the focus of evil in the modern world.” Not only did the comment anger the Soviets, it captured headlines across the United States and focused attention on the NAE.

Reagan made a return appearance at this year’s NAE convention in Columbus, Ohio. His rhetoric regarding the Soviets was more subdued. But the response he received from the 1,800 persons in the audience was enthusiastic.

The President told the evangelical Christians that “America has begun a spiritual awakening.” And he challenged the audience to be tolerant of differing viewpoints. “Please use your pulpits to denounce racism, anti-Semitism, and all ethnic or religious intolerance as evils.…”

He repeated his opposition to abortion, challenging Christians to find “positive solutions” to the problem. He reiterated his support for group prayer in public schools, tuition tax credits, and a strong national defense.

One of three standing ovations followed Reagan’s call for evangelical support of the proposed school prayer amendment. He also asked the audience to support a bill that would give students the right to use public school facilities for religious purposes. The following day, convention delegates passed a resolution supporting both measures.

While Reagan spoke, a few hundred demonstrators stood outside the convention center. Some were there in support of the President’s appearance, but others chanted anti-Reagan slogans. One man was arrested after he tried to force his way into the ballroom where Reagan was speaking.

A separate group of Reagan opponents staged a peace witness after the President left the convention center. The Christian pacifists, from Athens, Ohio, held placards and handed out leaflets outside the main meeting hall during the remainder of the NAE convention. One of them, Art Gish, a former Church of the Brethren pastor, was briefly detained by convention center security officers for violating a no-solicitation regulation. But he was released at the request of Darrell Fulton, NAE’s director of business administration.

In addition to their presence outside the meeting hall, the peace witnesses joined an ad hoc meeting approved by the NAE’s executive committee. Some 30 convention participants came to discuss the biblical teachings on war.

In business sessions, the NAE:

• Passed a resolution urging Congress and the President to reduce the federal budget deficit.

• Reaffirmed its opposition to the proposed Equal Rights Amendment as it is currently worded.

• Urged its member denominations, congregations, and organizations to conduct voter registration drives.

• Named U.S. Senator William Armstrong (R-Colo.) its 1984 Layman of the Year.

• Elected Robert W. McIntyre, a general superintendent of the Wesleyan Church, as its new president.

• Welcomed the 500,000-member Church of the Nazarene into membership. The NAE claims some 40,000 constituent congregations from 76 denominations, representing some 4 million evangelical Christians.

RON LEEin Columbus

The Crystal Cathedral Gains Only A Partial Tax Exemption

The California Board of Equalization has rendered a middle-of-the-road decision on the tax status of the Crystal Cathedral. The board’s determination was met with ambivalence by Robert Schuller and the congregants of his Crystal Cathedral church.

Had the board endorsed the recommendations of its investigators and totally denied the church tax-exempt status, the church would have lost all of the $465,000 it has paid. But with the ruling, as much as $302,000 could be returned to the church.

Schuller’s tax headaches began in 1982 when California authorities balked at the use of the Crystal Cathedral by profit-making businesses and performing artists. Schuller says his church exists to serve the community. He sees nothing wrong with making it available for community use as long as the activities are wholesome (CT, Aug. 5, 1983, p. 52).

Board investigators reasoned that since the church facility is rented—not donated—its tax-free status gave it an unfair advantage over other renters of building space.

In its recent judgment, the board granted tax-exempt status on the entire cathedral for 1981. (The board determined that concerts and rentals to profit-making organizations did not begin until late in the year.) For 1982, the board denied tax-free status on the church’s sanctuary and on about 30 of its auxiliary rooms. When the controversy arose in 1982, the church suspended the practices being questioned by the board.

Schuller and his congregation will now decide whether to let the matter rest or take it to court. That decision won’t come until the state determines the specific amount of money to be returned to the church.

Orange County tax assessor Brad Jacobs says he will need considerable guidance from the board of equalization if he is to carry out its wishes. He says the board’s ruling will make tax-exempt status more difficult to determine.

Ptl Explains Bakker’S Costly Hotel Visit

The PTL organization has clarified reports of talk-show host Jim Bakker’s stay at a Buena Vista, Florida, hotel.

CHRISTIANITY TODAY reported last October that Bakker spent four nights in a suite at the Palace Hotel at a cost of $1,000 a night (CT, Oct. 21, 1983, p. 44). Richard Dortch, corporate executive director of PTL ministries, says Bakker’s chief of security chose the expensive suite for security reasons. (The suite has eight rooms, but just one entrance.) Bakker had been receiving death threats, presumably because of the television personality’s aggressive antiabortion campaign. The incident was first reported in the Orlando Sentinal Star. CT carried its brief report after a PTL spokesman neither denied the accuracy of the Star article nor elaborated on it. Several months after the CT article was published, PTL released details of the incident to CT.

Dortch, a PTL board member who joined PTL’s staff last November, says it was his idea to get Bakker away from the organization’s offices in Charlotte, North Carolina, while security measures at PTL headquarters were reevaluated. Buena Vista, Florida, was chosen because it was a center for hotel construction. Dortch says Bakker and several members of his staff used the time in Buena Vista to tour construction sites to pick up ideas for a hotel now being built at PTL’s Heritage USA facility.

He says 14 people shared the costly hotel suite. Dortch says the bill was paid not from funds donated to PTL, but by Heritage USA, which operates as a business, not as a ministry.

PTL is one of only two major television ministries that submit to the guidelines of the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability. The other is the ministry of evangelist James Robison.

The U.S. Senate Confirms An Ambassador To The Vatican

The U.S. Senate has approved the nomination of William Wilson as the first American ambassador to the Vatican since 1867. The 81-to-13 vote indicated that there was not as much Senate opposition to Vatican diplomatic ties as many had thought.

Opponents of the appointment, including the National Council of Churches and Americans United for Separation of Church and State, stress that the issue is not Wilson but the principle of the separation of church and state. The National Association of Evangelicals and the Southern Baptist Convention also opposed the appointment.

U.S. Senator Richard Lugar (R-Ind.) testified that the appointment is not “the first step toward an erosion of the historical separation of church and state.” He said formal ties with the Vatican would be “good for U.S. diplomacy and security.”

In opposition, U.S. Senator Mark Hatfield (R-Oreg.) testified that in addition to violating the church-and-state separation principle, official ties with the Vatican would “demean the Pope’s status” by making him primarily a political rather than a spiritual leader.

The House Appropriations Subcommittee has approved the redirecting of funds to support the mission to the Vatican. The Senate is expected to do the same. When the matter leaves Congress, Americans United plans to file suit against the U.S. government. Spokesman Joseph Conn said the Vatican appointment “is clearly a violation of the Constitution.”

Fundamentalists Leave Jail, But Nebraska Church Schools Are Still In Trouble

After spending three months in a Nebraska jail, six fundamentalist Christian fathers are free. The men had been jailed for refusing to testify about the Faith Baptist Church School in Louisville, Nebraska.

Faith Baptist has wrangled with the state for seven years over teacher certification and school accreditation (CT, Feb. 17, 1984, p. 32). Its school continues to operate in defiance of Nebraska law.

After the men’s attorney, Michael Farris, appealed to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun to unravel what had become a legal quagmire, Cass County prosecutor Ron Moravec offered a compromise. He dropped the contempt charges against the men and canceled warrants for the arrests of their wives, who had fled the state with their children. In exchange, the men agreed not to send their children to Faith Baptist School until the state recognizes the school as operating legally. Warrants are still out for the arrests of Faith Baptist pastor Everett Sileven and his daughter, a former teacher at the school. The two also have fled the state.

Some 20 fundamentalist pastors who want to operate schools free from government control have been drawn into this bitter clash between church and state. In mid-February it looked as if the end was in sight. Nebraska governor Robert Kerrey endorsed a bill that fundamentalists found acceptable. The measure would have allowed church schools to operate without state certification as long as students tested favorably on national standardized exams. If students failed the tests, the state could prosecute parents, but not churches, according to the proposed legislation.

Coordinators of the protest movement in Louisville had charged earlier that Kerrey was being controlled by the Nebraska State Education Association (NSEA). The NSEA—which contributed heavily to his election campaign—opposes any change in certification laws.

But the governor shattered that notion by siding with the four-member commission he appointed to study the controversy. That commission determined that the state is denying First Amendment freedoms to churches that choose to operate uncertified schools.

NSEA public relations director Barc Bayley said he was “neither able nor willing” to explain why his organization opposed the student-testing proposal. The NSEA lobbied against the measure, so despite Kerrey’s support, Nebraska’s legislature defeated it by a 26-to-20 vote.

In mid-March, the legislature came one step closer to passing a bill that calls for the testing of teachers prior to permitting them to teach. Fundamentalists oppose the requirement, saying it is merely another form of teacher certification.

Robert Gelsthorpe, pastor of the North Platte (Neb.) Baptist Church, had been hoping the legislature would pass a bill he could accept. The pastor was reporting to the local sheriff’s office for six hours every day his uncertified school held classes. Now he will report to his school instead. He expects to be arrested and sentenced to a jail term. Gelsthorpe says he hopes the legislature will reconsider its stance before it recesses on April 6.

Meanwhile, the Nebraska Supreme Court has agreed to hear the oral arguments of constitutional attorney William Ball, who is representing Park West Christian School in Lincoln, Nebraska, in its legal battle with the state. Ball says the Nebraska courts have not heard a thorough presentation of the First Amendment issues pertaining to the church-school controversy.

World Scene

The Bible was published in four additional languages last year. The American Bible Society says the entire Bible is available in 283 languages. At least one book of the Bible is available in 1,785 languages.

Grenada’s preinvasion Marxist government had prepared plans to suppress the Caribbean nation’s churches. The U.S. State Department says documents seized after the American invasion show that the government feared a major church-led resistance. The documents indicate that the government considered monitoring the church’s activities, membership, and financing.

Church officials estimate that 20 to 30 percent of Puerto Rico’s 3.1 million inhabitants have left the Catholic church for Protestant churches. Most of the switching occured after Protestants stepped up their missionary efforts less than 40 years ago.

The government of Singapore is encouraging well-educated people to have more children and less-educated people to have no more than two. The program is based on the theory that children born to scholars will have a better chance to become productive citizens. Educated mothers will be given priority when enrolling their children in the best schools. Second on the list will be less-educated mothers who agree to be sterilized after their first or second child.

Japan has only one Protestant church for every 19,400 people. The Church Information Service says several major Japanese cities, with a combined population of more than 370,000, do not have any Protestant congregations.

Roman Catholicism is no longer Italy’s state religion. An agreement signed by the Vatican and the Italian government curtails some of the church’s privileges. Religion classes in public schools will become elective courses. Previously, children were required to attend. In addition, church marriage annulments must now be approved by Italian courts. However, the Vatican will remain a sovereign state run by the Pope.

A Romanian Baptist human rights leader was found dead in January. Nicolae Traian Bogdan had been missing for a month. A medical examiner said Bogdan, 25, committed suicide. But Bogdan’s associates suspect that he was murdered. The Baptist leader was wanted by the secret police for unapproved religious activities.

If the growth of Mozambique churches continues at its present rate for the next 20 years, the entire country will be evangelized. Robert Foster, international director of Africa Evangelical Fellowship, estimates that in some districts more than 50 percent of the people are born-again Christians. The government expelled missionaries in 1959, but has eased restrictions on religious activities in recent years.

The Africa Inland Church plans to open a missionary college in Kenya by May 1985. The college will train nationals for outreach into unevangelized areas in Kenya and surrounding countries. It will be the first school of its kind in east and central Africa.

Yugoslav officials held a Baptist leader for questioning on the opening day of the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo. They also withdrew permission for Baptists to distribute leaflets inviting Olympics visitors to a coffee house in a church. Authorities ordered the Baptists to collect all leaflets already distributed, but they did allow the coffee house to remain open.

Some 197 million people—about 4 percent of the world’s population—consider themselves atheists. In addition, statistics released by the Vatican indicate that atheism is the state religion in 30 countries. The number of atheists increases by about 8.5 million each year.

Deaths

G. Aiken Taylor, 64, president of Biblical Theological Seminary, Hatfield, Pennsylvania, for 24 years the editor of Presbyterian Journal, moderator of the Presbyterian Church in America General Assembly (1978), former vice-president of the National Association of Evangelicals; March 6, at his home in Colmar, Pennsylvania, of cardiac arrest.

Roland H. Bainton, 89, professor emeritus of church history at Yale Divinity School, author of Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther; February 13, in New Haven, Connecticut, after an extended illness.

Southern Baptist Committee Votes Against Full Ties With Canadians

For several years, the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) and some Canadian Baptist churches have considered establishing formal ties. Sixty-two Baptist congregations in Canada have ties to Southern Baptist regional bodies in either Ohio or the Pacific Northwest.

At issue is whether the Canadian Baptist churches should be permitted to send messengers (delegates) to the annual Southern Baptist denominational meeting (CT, March 16, 1984, p. 48). Chances of that happening in the near future appear slim. A 21-member committee appointed to study the issue has come out against the seating of Canadian messengers.

Specifically, the committee concluded that the SBC constitution should not be changed to add the words “and Canada” to define the geographical boundaries of the 14-million-member denomination. The committee will forward its recommendation to the SBC convention in June.

Despite its stand against formal ties, the committee urges “increasing involvement between churches, associations, and state conventions in the United States and churches in Canada.” The committee also recommends the formation of a Canada planning group, consisting of representatives from several Southern Baptist agencies, including the home and foreign mission boards.