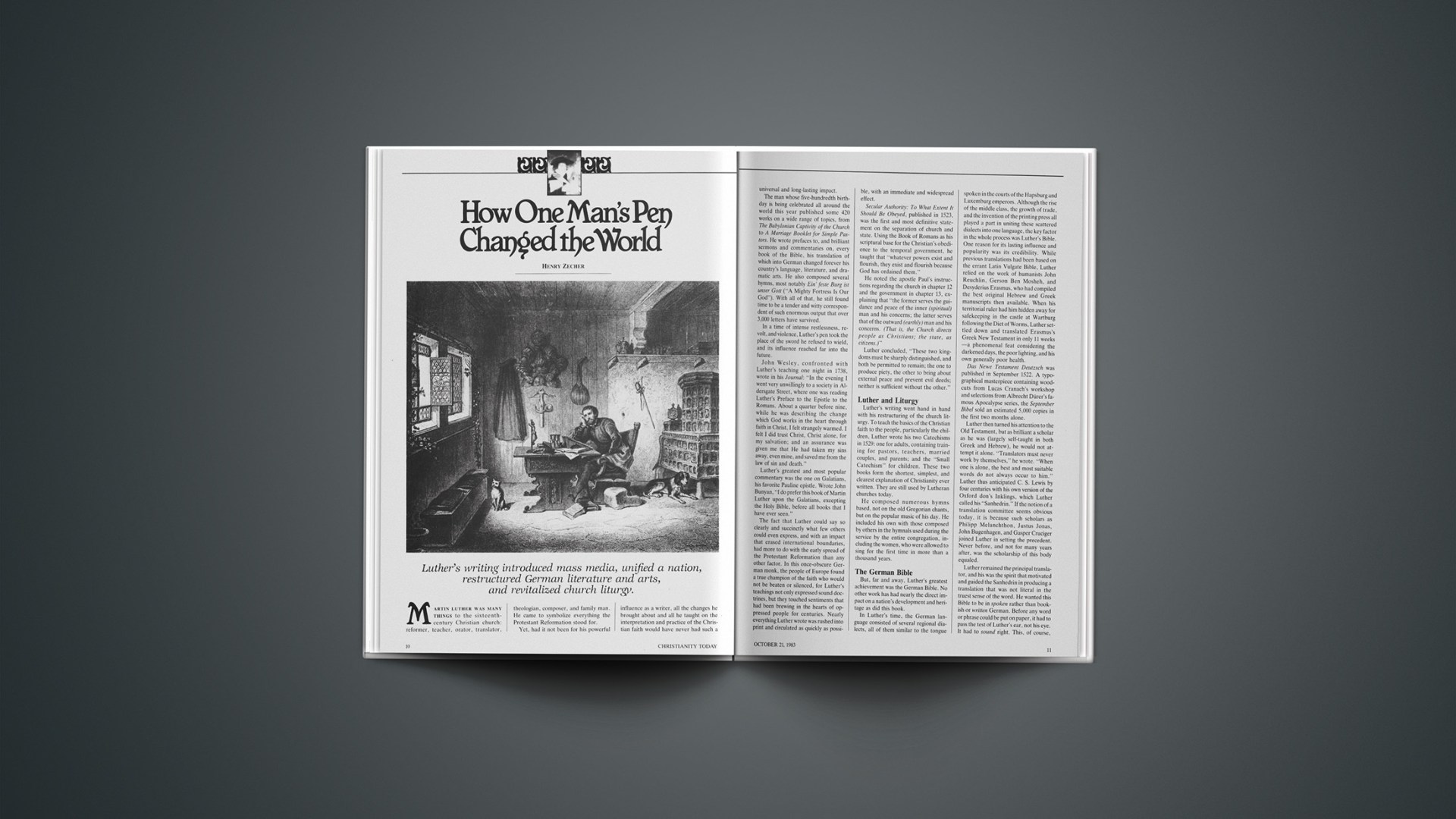

Analyzing character traits from a person’s handwriting is considered more science than superstition today. Witness the many businesses that use scientific handwriting analysis in job testing and interviews. A study of Martin Luther’s handwriting through the eyes of a handwriting expert reveals some likely characteristics of the great Reformer.

On November 10, 1483, at Eisleben, Germany, a child was born who would have the greatest effect on Christianity of anyone since Jesus Christ. His name was Martin Luder—which he later changed to Luther—the son of peasants, the father a laborer in the copper mines of the Harz Mountains.

What kind of a man was Luther? Using graphoanalysis, a scientific method of determining personality characteristics from the strokes made in handwriting, we can learn much about the man. Graphoanalysts think of handwriting as “brainwriting,” because the brain dictates the way we write. The individual actually has little control over many of the formations in his writing. (Perhaps you’ve noticed that you write differently at different times. That’s because you don’t always feel the same.)

The fairly heavy strokes in Luther’s writing show that he felt things deeply. Many of those feelings remained with him a long time, some for life. The forward slant of the writing indicates that emotion played an important part in his thinking and that he had feelings for people and things around him. He was not the kind of monk to crawl into his shell and isolate himself from the world.

Life to Luther was a serious business, for he had strong convictions of right and wrong. When he felt something was wrong, he could become quite depressed over it. The blunt endings on most of his words indicate an ability to make decisions readily. Having made a decision, he usually felt sure it was the correct one, which is shown by the several rigid downstrokes going straight to the baseline.

The narrowness of some of his circle letters (a, o, e, d) shows that he did not always accept the viewpoints of others, especially if they did not conform to his own strict codes and beliefs. The roundness of most of the dots over the dotted letters indicates a strong loyalty both to his principles and to people he felt deserving of it.

Luther was an energetic thinker, analyzing ideas and probing into subjects that aroused his interest. The frequent breaks between letters means that he used instinctive or “gut” feeling in deciding on a course of action. His active imagination tended to run to abstract subjects (philosophy, ethics, religion) more than to material things, although he was not without imagination in that area.

Strong drives made him tackle a task vigorously and sometimes impetuously, with lots of confidence in his ability to see the job through. His accomplishments were due more to energy and conviction than to being well organized; he did not attain leadership and prominence through a desire for responsibility or self-importance but rather through a dogged, energetic pursuit of his ideals. It was more important to Luther to satisfy his conscience than to gain fame or fortune.

The writing shows a stubborn, defiant nature—small wonder that he defied the papacy by nailing his 95 theses to the church door in Wittenberg! Luther did not handle people with kid gloves, being too direct and inclined to speak his mind and let the chips fall where they may. One would always know exactly where one stood with Martin. He was prone to argue and often lost his temper, and there must have been many people who found him difficult in spite of his great honesty and sincerity. He did not seek popularity, but he was the kind of man who would attract some loyal friends and followers.

What kind of career would Luther have followed if he hadn’t become a monk? The aptitudes revealed in his handwriting give us some clues. His depth of feeling and a generally creative nature show a leaning to the arts. (We know that he loved music and played well on the lute.) Literary aptitude is indicated as is some appreciation of the visual arts. He would have made a poor politician, being much too straight-forward and truthful.