NEWS

They got 14 years in jail for smuggling drugs; they say they didn’t do it (sort of); Colson can’t help them.

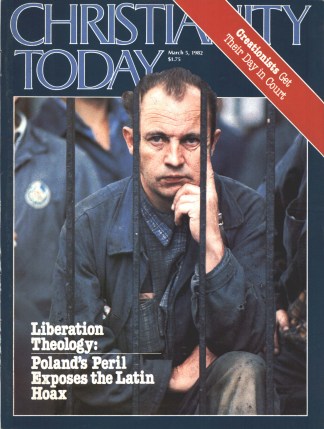

Charles Colson is accustomed to dealing with hardened criminals through the organization he heads, Prison Fellowship (PF). Now, however, he has embarked on a concerted campaign to free two American women tourists in their sixties who have been sentenced to 14 years in an Australian prison on a drug-smuggling conviction. The women say they were framed. The case of the “drug grannies” is becoming something of a sensation in Australia.

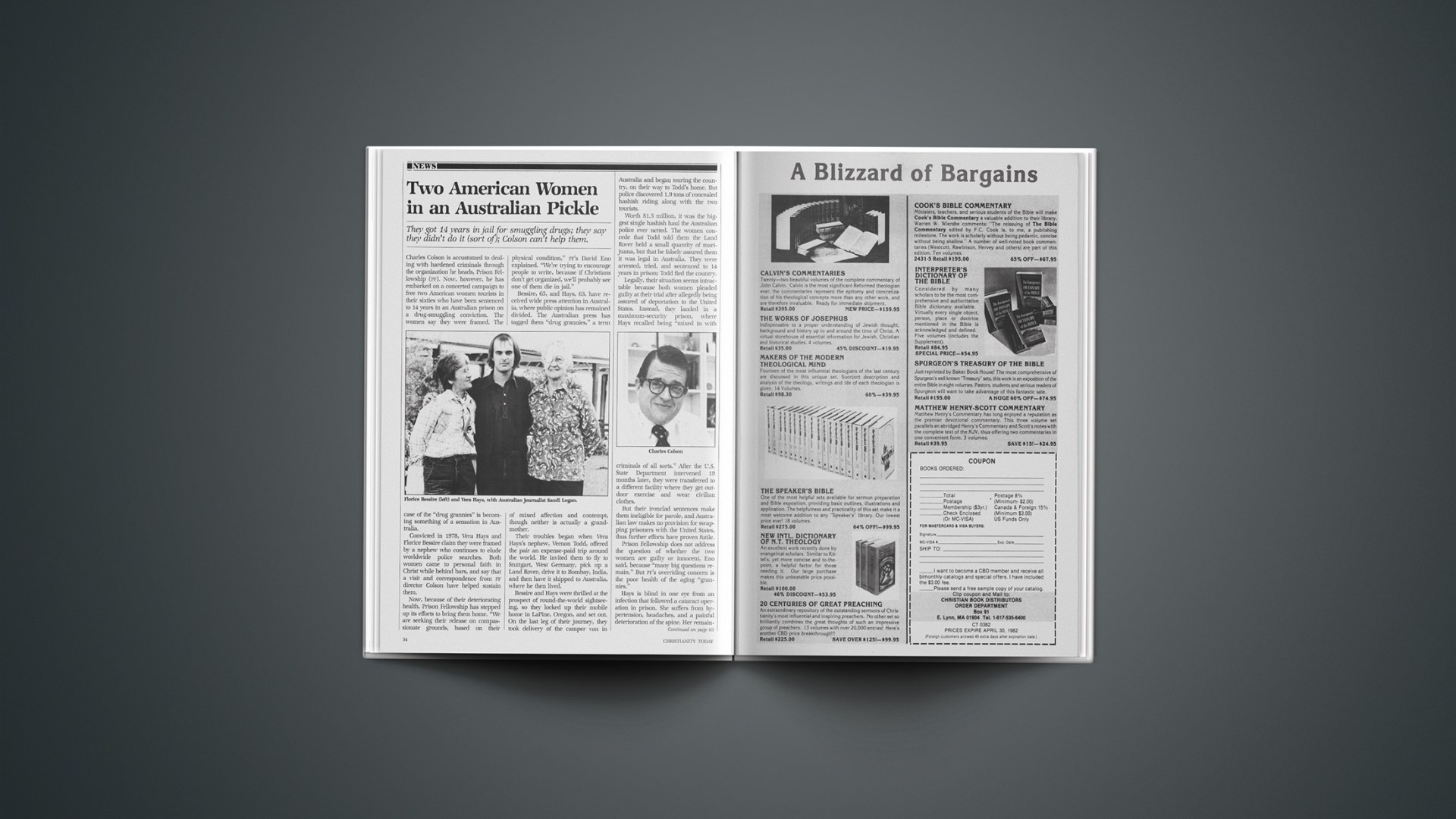

Convicted in 1978, Vera Hays and Florice Bessire claim they were framed by a nephew who continues to elude worldwide police searches. Both women came to personal faith in Christ while behind bars, and say that a visit and correspondence from PF director Colson have helped sustain them.

Now, because of their deteriorating health, Prison Fellowship has stepped up its efforts to bring them home. “We are seeking their release on compassionate grounds, based on their physical condition,” PF’S David Eno explained. “We’re trying to encourage people to write, because if Christians don’t get organized, we’ll probably see one of them die in jail.”

Bessire, 65, and Hays, 63, have received wide press attention in Australia, where public opinion has remained divided. The Australian press has tagged them “drug grannies,” a term of mixed affection and contempt, though neither is actually a grandmother.

Their troubles began when Vera Hays’s nephew, Vernon Todd, offered the pair an expense-paid trip around the world. He invited them to fly to Stuttgart, West Germany, pick up a Land Rover, drive it to Bombay, India, and then have it shipped to Australia, where he then lived.

Bessire and Hays were thrilled at the prospect of round-the-world sightseeing, so they locked up their mobile home in LaPine, Oregon, and set out. On the last leg of their journey, they took delivery of the camper van in Australia and began touring the country, on their way to Todd’s home. But police discovered 1.9 tons of concealed hashish riding along with the two tourists.

Worth $1.5 million, it was the biggest single hashish haul the Australian police ever netted. The women concede that Todd told them the Land Rover held a small quantity of marijuana, but that he falsely assured them it was legal in Australia. They were arrested, tried, and sentenced to 14 years in prison; Todd fled the country.

Legally, their situation seems intractable because both women pleaded guilty at their trial after allegedly being assured of deportation to the United States. Instead, they landed in a maximum-security prison, where Hays recalled being “mixed in with criminals of all sorts.” After the U.S. State Department intervened 19 months later, they were transferred to a different facility where they get outdoor exercise and wear civilian clothes.

But their ironclad sentences make them ineligible for parole, and Australian law makes no provision for swapping prisoners with the United States, thus further efforts have proven futile.

Prison Fellowship does not address the question of whether the two women are guilty or innocent, Eno said, because “many big questions remain.” But PF’S overriding concern is the poor health of the aging “grannies.”

Hays is blind in one eye from an infection that followed a cataract operation in prison. She suffers from hypertension, headaches, and a painful deterioration of the spine. Her remaining eye also has developed cataracts. The older lady, Bessire, says her worst moments are “when I see Vera suffering.” Bessire herself contends with chronic arthritis and has had a series of minor infections since being imprisoned.

Despite their physical trials, the two say their new-found faith in God is a source of constant strength. “My communication lines with God were down, but since I’ve landed in this predicament I have realized what had happened to me,” Bessire recounted in an interview with Australian journalist Sandi Logan. “Prison is one place you really sit down and take stock of yourself, and realize your shortcomings, and there were many. God has forgiven me and even in here I can find peace and glory in our Lord.”

Hays said she was consumed with bitterness and hatred toward her nephew after being jailed. “I had to stop that. I had to turn to God and pray to God to stop my hating and to turn it to love and forgiveness.” Hays also prayed for a sign that the Lord was listening. She is sure it arrived in the form of a visit from Mrs. Charles Thornley, active with Gideons International in Australia. The Thornleys visited the two women every Sunday and eventually led Hays to Christ.

Since then, fellowship provided by PF/Australia volunteers and others have bolstered the pair’s spirits and enabled them to minister as well. Hays said, “We have helped a lot of young girls who we have taken under our wing and set on the right track.”

In a letter to PF International’s vice-president, Kathryn Grant, Bessire and Hays wrote, “The times have been very trying, but we know our Lord is omnipresent, and no matter where we are, his hand never leaves ours. Our faith is food for the soul, and we will never go hungry.”

Their ardent wish is to return home, but only the Australian government can grant a release. Colson has repeatedly appealed to authorities to “temper justice with mercy.”

BETH SPRING