When Eric Foley heard that police had detained six Americans in late June for doing a “rice-bottle launch” in South Korea, he felt a dull wave of dread pass through his body.

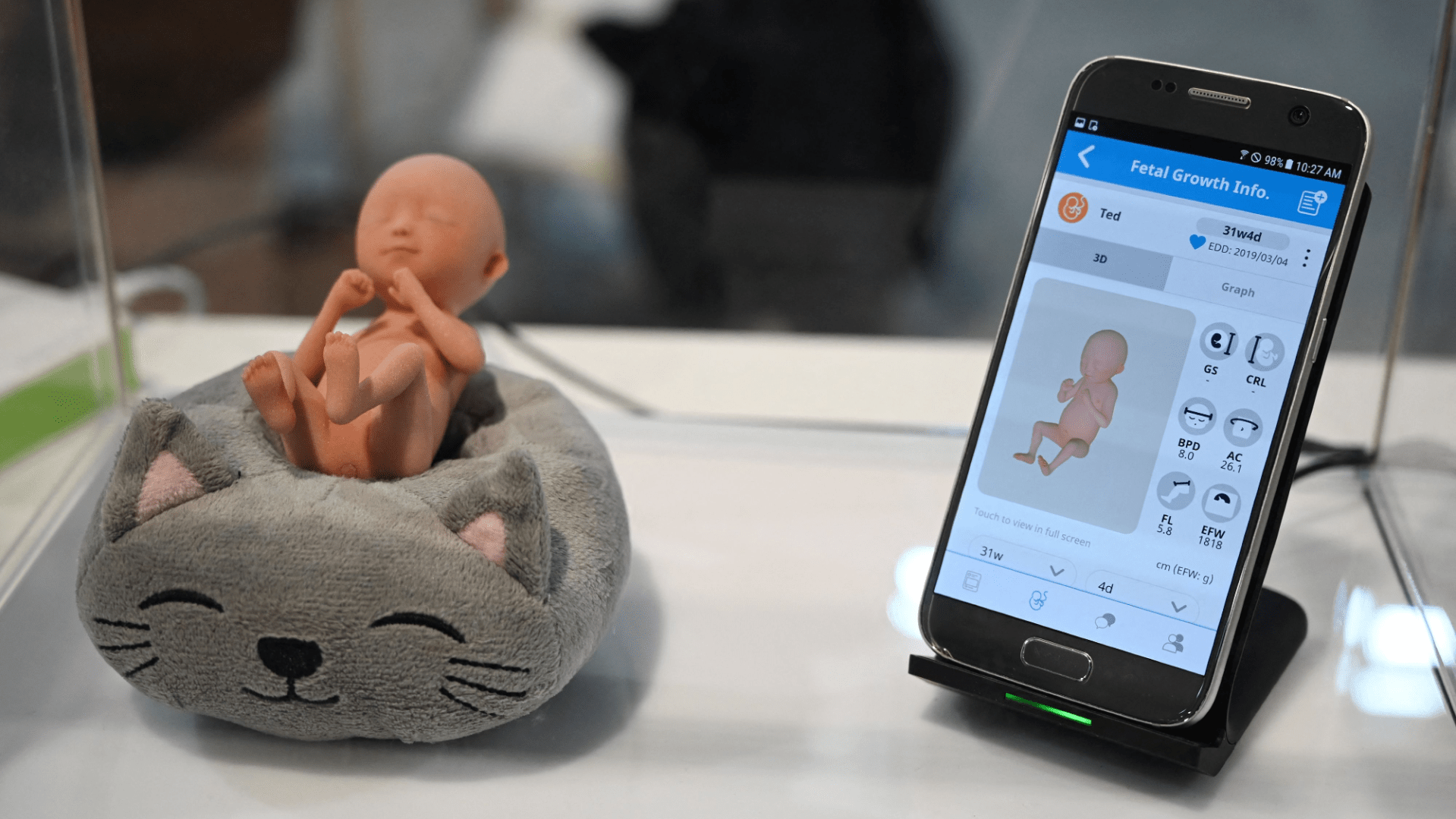

The group had attempted to throw 1,600 plastic bottles filled with Bibles, rice, $1 bills, and USB sticks in the sea off the shore of Ganghwa Island, which lies close to the southern part of North Korea, in hopes that they would float toward the North. Police investigated the Americans for allegedly violating a law on the management of safety and disasters.

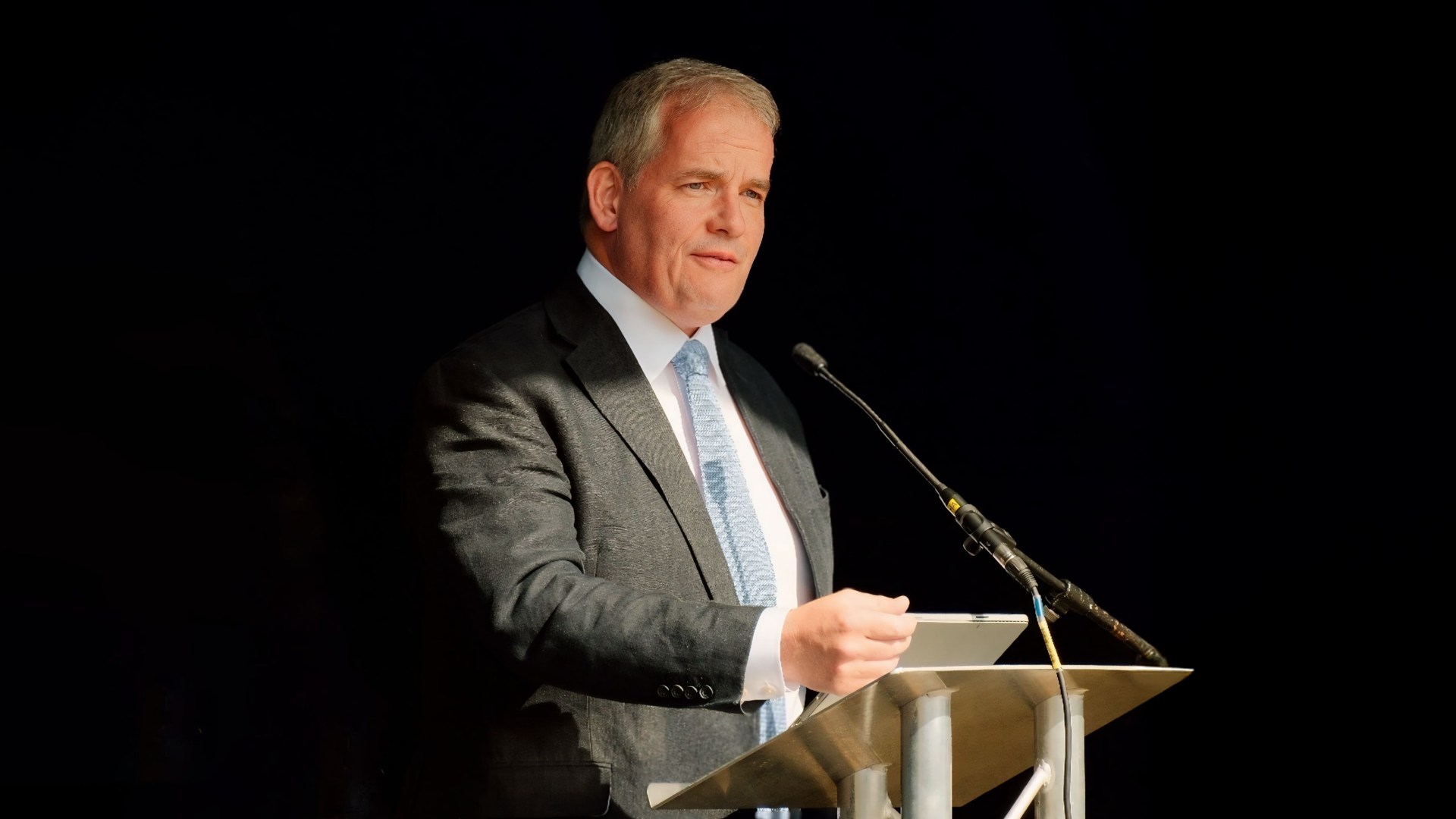

Foley immediately recalled June 2020, when South Korean police charged him and his organization, Voice of the Martyrs Korea (VOMK), for using balloons to send Bibles to North Korea. After an investigation, police ultimately decided not to pursue the charges against him.

“None of this dampened my resolve to keep my promise to underground Christians to get more Bibles into North Korea,” Foley said.

Information on who the six Americans are has not been released. A US State Department spokesperson told CT they are aware of media reports of US citizens detained in South Korea and are monitoring the situation but could not provide further comment due to citizens’ privacy.

Meanwhile, Foley said he fielded inquiries from both Korean and American authorities about the group that was detained. Yet he and other groups working to reach North Koreans have no clue who these individuals are.

“We have no connection to this group at all and no awareness of their activities,” Foley said. He feels troubled by how they had come to South Korea to “try to do this work that looks so simple but for which so many have paid such a high price.”

Christian nonprofits and groups in South Korea that have served North Korea for decades worry that the incident will hamper efforts to reach the reclusive country. Officially known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), North Korea ranks on the World Watch List as the world’s most dangerous place to be a Christian—being found with a Bible can lead to imprisonment in a labor camp or even execution.

Depending on the party in power, the South Korean government has held different views on sending information into North Korea, whether by bottles, balloons, or loudspeakers. Under the Moon administration, which sought reconciliation with the North, the government passed a bill prohibiting acts that violate an inter-Korean agreement, such as disseminating leaflets by balloon to North Korea.

But under the conservative Yoon administration, the Unification Ministry, a government body responsible for inter-Korean relations, reversed its stance. And in 2023, South Korea’s Constitutional Court scrapped the law, saying that it curbed free speech excessively. Local police, however, continue to monitor balloon activity along the border to protect citizens from reprisals from North Korea.

The recently elected president Lee Jae-myung has pledged to rekindle dialogue and reopen communication channels with the North.

In a two-hour press conference on July 3 marking his first month in office, Lee vowed to improve relations with the North. “It’s foolish to completely cut off dialogue,” he said. “We should listen to them even if we hate them.”

In June, as a means of reducing tensions between the two Koreas, Lee ordered the South Korean military to stop broadcasting anti–North Korea propaganda along the border, and the Unification Ministry called for activists to stop sending anti–North Korea leaflets.

Yet the Virginia-based Defense Forum Foundation believes that rice-bottle and balloon launches are needed. For years, it has partnered with North Korean defectors who engage in exactly the activities the six Americans are accused of—throwing bottles filled with items like rice, $1 bills, USBs, and small Bibles off the coast of South Korea—to get information into the North.

But Suzanne Scholte, the group’s president, doesn’t know who the detained Americans are. The entire “Operation Truth” team had recently returned from a trip to Europe for North Korea Freedom Week when they heard about the arrests. Beyond bottle launches, the group also helps send information into North Korea by launching helium balloons, floating giant plastic bags on ocean currents, and broadcasting a radio program.

Scholte even questioned whether the arrest was a fake story to intimidate groups like hers.

“I just do not find it plausible that six Americans would be doing something like that, because it’s North Korean defectors that are doing it,” she said. “[They] are the most effective at carrying these projects out because they’re the ones that develop these methods, because they know how to get stuff in.”

She notes that defectors often point to receiving information from the outside world, including from leaflets or short-wave radio, as the catalyst leading them to escape. So despite pushback from the current administration and fears of arrests, the group plans to continue its work quietly. “We’ll just be more careful, and we’ll have to develop new routes,” she said.

Balloons launched by different groups—both religious and political—have carried items like a leaflet dispenser, tiny battery-powered loudspeakers, USB sticks containing K-pop music and Korean dramas, and abridged versions of the Bible.

In response, North Korea sent more than 7,000 balloons filled with trash like toilet paper, soil, and batteries into the South last year to retaliate against what it considered the “frequent scattering of leaflets and other rubbish” by groups in South Korea.

Foley prayed that God would prevent other foreign groups from copycat launch efforts. He fears their actions may lead to larger, unintended consequences. Although the six Americans can leave South Korea, this incident may lead to greater scrutiny from government officials and greater public concern over the work that groups like VOMK do to serve North Korea, Foley said.

Jongho Kim, chairman of the Northeast Asia Reconciliation Initiative (NARI), agreed. The nonprofit brings believers from East Asia and the US together to discuss what healing and engagement look like in a region fraught with political tension.

In Kim’s view, the Americans’ detention is not an issue of religious persecution but a legal matter based on the South Korean government’s laws on engagement with the North.

“Actions that are not coordinated with or permitted by the South Korean government can easily be viewed as provocations, undermining the fragile new mood of dialogue,” he said.

North Korea closed its borders when the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020, and it has largely remained closed since then. After opening up the northeastern city of Rason to Western tourists in March, North Korea abruptly stopped more visitors from entering without citing a reason.

These ongoing border closures have also affected how Christian nonprofits serve there, a CT report noted last year.

Kim feels deeply concerned by how the incident may hamper NARI’s efforts to foster dialogue and build relationships through forums that encourage discussion on healing divides. “The work of reconciliation and engagement with North Korea is incredibly delicate and built on years of patient trust-building,” he said.

But he looks to the parable of the sower for guidance. The long-term work of reconciliation is like patiently cultivating good soil so that, at the right time, a seed can produce a lasting harvest, he said. “Actions that are perceived as reckless, however well-intentioned, risk hardening that soil for everyone.”

Foley agrees that patience is key when it comes to serving the North. But he also urges Christians not to keep thinking that North Korea is “closed” to the gospel.

It is illegal to send Bibles into North Korea from South Korea, China, or Russia, Foley said. Despite this, VOMK delivers an average of 40,000 Bibles into the DPRK each year, although for security reasons, Foley can’t say how. The nonprofit sends one or two Bibles at a time, and it may take Foley and his team a year to get a Bible to a difficult location. He noted that they play the long game, often planning years in advance and coming up with multiple backup plans so that their distribution isn’t interrupted.

As a result of their and other Christians’ work, the number of North Koreans who have seen a Bible has increased by 4 percent each year since 2000, according to the 2020 White Paper on Religious Freedom by the North Korean Human Rights Database.

“More North Koreans inside North Korea are seeing Bibles than at any other point in history, including the time of the Great Pyongyang Revival in the early 1900s,” Foley said.

Foley continues to pray for underground Christians in North Korea. In his view, the first thing people should do before undertaking any activity to serve North Korea is to take the time to ask believers there, “What would be helpful to you?”

Additional reporting by Angela Lu Fulton.