Many corridors crisscross political pathways at the National Council of Churches.

The upper reaches of New York’s Riverside Drive, it might be thought, are no place for an evangelical—and an alien, to boot. I hurried past Union Theological Seminary, only to find myself in Reinhold Niebuhr Place. On my right was Riverside Church, built in 1930 by decree of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., so that Harry Emerson Fosdick might continue “fearlessly teaching the modern use of the Bible,” and further his crusade to insure that the fundamentalists should not win.

On my left was the $20-million, 19-story Inter-Church Center, which, “sheathed in Alabama Limestone,” stands on a block-long site made available by Rockefeller, who also contributed handsomely toward construction costs. Dedicated in 1960, the center houses some two dozen agencies, and is known in the trade (a secular journalist told me) as “The God Box.”

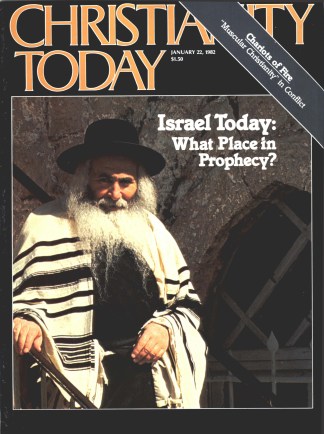

At the elevators, visitors come under unobtrusive security scrutiny; an upper-floor notice from the building superintendent warns against thieves given to discarding empty billfolds on the stairways. A sizable section of the building is occupied by the offices of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. (NCC). This was my destination. The editor of CHRISTIANITY TODAY wanted an article on that body, and had fingered me for the task. Since he cannily refrained from telling me how to handle it, I began by finding out what the NCC says about itself.

The preamble to its constitution calls the NCC “a cooperative agency of Christian communions seeking to fulfill the unity and mission to which God calls them. The member communions, responding to the gospel revealed in the Scriptures, confess Jesus, the incarnate Son of God, as Savior and Lord. Relying on the transforming power of the Holy Spirit, the council works to bring churches into a life-giving fellowship and into common witness, study and action to the glory of God and in service to all creation.”

Its 32 member bodies include Serbians and Swedenborgians, Friends and AME Zion. Combined membership tops 40 million. It does not include Roman Catholics, Southern Baptists, various Lutheran and Reformed bodies, and a large number of smaller conservative evangelical groups. The NCC’S 266-strong governing board meets twice yearly.

I perused “A Message to the Churches” from its May 15, 1981, meeting. “The polity of the new [Reagan] administration,” it declared, “is not just to cut back on human services, but to deny that people are entitled to them.” It was, moreover, giving away public lands to private entrepreneurs; abandoning old international friends and commitments; proposing to make the U.S.A. “Number One” in the world militarily, but not in humanitarian projects; and seeking “to reverse the record of half a century.”

All good knockabout stuff, even if it did ring in parts like a Democratic manifesto. The same meeting nonetheless approved a message to USSR President Brezhnev, urging freedom for Sakharov and other “prisoners of conscience.” I wanted now to learn less about the headline catchers and more about bread-and-butter matters.

The NCC, I found, has provided over five billion pounds (weight) of food, clothing, and health supplies in emergency situations around the world. It supplies materials for church schools and stewardship campaigns; is involved in projects concerning child and family justice; cooperates in producing religious radio and TV programs on the major networks; brings people together for biblical scholarship (it holds copyright to the RSV); works to improve relationships with those of other faiths, such as Muslims and Jews; champions the rights of minority groups; and has coordinated the placement of over 300,000 refugees in U.S. communities.

When I sought interviews with top NCC executives, the media department arranged these with promptness and efficiency. Two key staff people who would be away during my visits made themselves available for extended telephone interviews. There was no instinctive distrust of questing journalists who might have been about heresy-hunting business. Whatever else I was to find, the NCC was at least sound on courtesy.

Claire Randall has been NCC general secretary for the past eight years. Formerly an artist and religious education specialist, she chaired a task force that recommended relaxation of the NCC’S stand against abortion, and immediately prior to 1974 was an executive with Church Women United.

She fielded a little gingerly my inquiry about evangelical representation on the NCC staff. Naturally the council would not wish to discriminate against such people (many of whose denominations are council members), but the crux seemed to be whether evangelicals would be “comfortable” in staff posts that often called for a breadth of outlook that might be unacceptable to those of a more conservative viewpoint. On the wider front, Randall pointed out, nonmember groups often cooperated with the NCC. Asked why the NCC had held no general assembly since 1972, Randall responded that this was due largely to financial considerations.

I asked her about the NCC cable last May to Irish Roman Catholic and Protestant leaders, expressing “profound regret” at the death of hunger striker Bobby Sands. Was this action not likely to be misunderstood by British Christians unless balanced by expressed sorrow for the innocent victims of IRA bombs and bullets?

I repeated the same question later to outgoing NCC president William Howard, but neither official seemed personally well informed about Northern Ireland, or about whether the British Council of Churches had been consulted before the cable was sent. Howard indicated that in this instance they had relied heavily on J. Richard Butler, who, I discovered, was director of the NCC’S relief and development work in the Middle East and Europe.

When I raised the matter of possible NCC membership for the Metropolitan Community Churches (the so-called gays), Randall referred me to a statement by Arleon Kelly, head of constituent membership affairs. This read: “Considering the historical position and doctrinal practices of the communions that compose the National Council of Churches of Christ, it appears to me extremely doubtful that 21 of the necessary members would vote for the inclusion of the MCC.”

Here I pause for ironical reflection. The NCC might conclude that to have drawn a circle that takes in as many as possible might not have been such a good idea after all. The MCC feel they fulfill the formal requirements for membership. It is hard to imagine the NCC rejecting such an application solely on biblical grounds. For the council to have recourse to “the historical position and doctrinal practices” of member denominations has an oddly archaic, even disingenuous, ring about it. On other issues, a one-time identification with the Westminster Confession, for example, the rock on which Fosdick the Presbyterian had foundered in 1925, did not noticeably sway some NCC groups in 1981.

In addition, for the NCC to reject the MCC without reason adduced might be regarded as contravening its own vaunted emphasis on religious toleration—and justice would not have been seen to be done. But as news and information executive director Warren Day reminded me, the MCC’S application was not received until mid-September, and had not yet come under official scrutiny.

Ncc president m. William Howard welcomed me to his offices on the eighteenth floor. Born in Georgia the year after World War II ended, he grew up in Americus, “one of the toughest anti-civil rights towns in the nation,” but a grandmother had taught him an “informed compassion for racists.” Another great influence on his life was Martin Luther King, Jr., who was assassinated during Howard’s senior year at Morehouse College, Atlanta. “In Georgia,” he said, “there is no distinction between social justice and a living Christian faith.”

I found Howard less intractable than many professional conciliarists. “We have had moments of arrogance and failure,” he admitted (I found myself wishing that Geneva was listening). To his condemnation of South Africa he was willing to add a postscript that showed fellow feeling toward white politicians there who had taken a public stance against apartheid and other evils.

Howard is a strong advocate of the Program to Combat Racism, and would not agree with me that soon after its inception the PCR changed its target from racism generally to white racism. This had always been implicit, he declared. (The 1980 wcc central committee meeting had in fact “noted” the existence of nonwhite racism.)

I asked the president about his reference to “a scriptural mandate for unity.” He recounted the pragmatism that brought pre-NCC societies together, chiefly concerned with such things as relief work. “Not till ten years later did we dare to talk about theology. There is now a greater and growing appreciation of the central role of theological perspectives.” He saw this as an “anxiety-producing” area, but division was sin, and it was necessary that Christ’s call to unity should be clearly heard.

Questioned about his three-year term of office, which terminated in November, he said he had been told that no president had been exposed to so many people. “The council is concerned now to be a religious organization to be reckoned with. More people have seen in the NCC some aspects of religious expression they might like to see in the local church.” He added that the NCC had started conducting Bible study only during this period, and that the tendency was growing.

Was it true, I asked, that he thought that blacks in his native Americus had fared better in segregated schools than they did now under desegregation? No, he would put it differently. Black students in certain integrated school systems in both North and South were not always getting the attention they formerly had from the loving and supportive teachers of the segregated days.

Howard’s fellow black, Kenyon C. Burke, is associate general secretary for the NCC’S Church and Society division. The latter concerns itself with such matters as economic, social, and racial justice, the disadvantaged, the unprotected, the vulnerable, rights of women, religious and civil liberties, international affairs, and the Vietnam generation, including veterans and their problems (especially those in prisons, many of whom are black or Hispanic).

Burke’s division was campaigning for a 10-year extension of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965. The VRA promised, said Burke, and it delivered. Census data from 1964 to 1976 show a 60.7 percent rise in black voter registration in Mississippi, 35.1 percent in Alabama, 31.9 percent in Louisiana. There was also a significant upsurge in Hispanic voter registration. Voter rights had marched on since Selma in 1965, but while rigged literacy tests and intimidation of blacks have gone, there are now “more sophisticated evasions and gerrymanders.” Burke called on religious bodies to support an act designed to purge racism, bigotry, and “all its ugly residuals.”

That led on naturally to a question: Had an official NCC decision been taken not to support Bob Jones University over the threatened IRS withdrawal of its tax exemption status?

This proved to be a wormy can, but Burke tackled it candidly. The issue had caused a difference of opinion within the NCC, which on occasion was called “to stand up for very unpopular people.” A working group on religious liberties favored entering the case on BJU’S behalf; a working group on racial justice disagreed because of BJU’S discriminatory policies.

At first it seemed that BJU would find an improbable ally, but I gather that the current consensus in NCC counsels warns that this is not an opportune time to support religious liberty at the expense of racial justice.

Would his division support bodies such as the Church of Scientology and the Unification Church against the use of conservatorships by zealous deprogramers? (A conservator is someone designated to assume and protect the interests of an incompetent.) The NCC, came the reply, was opposed to deprograming activities. And brainwashing? Yes. From whatever source? Yes.

Burke pointed to the need to show that “there is a biblical base for social justice.” He criticized those who, with no personal knowledge of real poverty, “are easily moved by stereotypes that say the poor are irresponsible and inept people.” He recommends nightly readings of Matthew 25:31–46—a passage that hits the sort of strong eschatological note not commonly featured in conciliar parlance.

Next, I was interested in NCC finances. The budget in recent years has varied between $19.5 million and $30 million. The fluctuation is concerned with emergency programs where the council acts in effect as an administrative and financial agent. Separate accounts are kept with respect to Church World Service, the NCC’S relief arm, whose 1980 budget was over $61 million.

The highest source of “real” NCC income (39 percent) comes from member denominations or church-related agencies. In expenditure, 78 percent goes “to minister outside the U.S. through evangelism, education, healing, community development, and relief to those in need.” The next largest figure is 6 percent that goes “to extend the Gospel ministry through Christian commitment and witness across the U.S.” Only 3 percent of expenditure goes “to administer, supervise and finance the council.”

David ng, San Francisco-born Presbyterian minister and D.D. of Westminster College, Salt Lake City, heads the NCC’S Education and Ministry division. He emphasizes his “deep concern for evangelism and church growth, and a very solid practice of spiritual discipline.” He thinks that one of the most refreshing developments of the 1970s was “a renascence of evangelical activism.” He claims that the NCC has had a part in the increasing openness of mainland China. Drs. Howard and Randall were going there in November at the invitation of Bishop Ting.

Ng is unhappy about press reports that the NCC is planning to produce a “de-sexed” version of the Bible (a 1990 publication of the revised RSV is anticipated). He assures me that the Bible committee, under the chairmanship of Dr. Bruce Metzger, is “firmly committed to a literature translation, as the text permits.” (Over the RSV, Howard told me earlier, the NCC had had “the meanest mail.”) The NCC is, however, planning an “inclusive-language” lectionary. This will avoid the masculine-biased terminology that deeply offends some women who feel it “cuts them off from full participation in the community of the Church.” Inclusive language, claims an NCC leaflet, “helps us to proclaim the identity of all of us as heirs of God.”

The Reverend Joan Campbell of the NCC’S Local and Regional Ecumenism Commission, who was in Washington for the Solidarity Day demonstration on September 19, felt that evangelicals too readily assume that “ecumenical people” are not also pastoral people. They do not understand the depth of the faith held by many such, she opined, nor do they always recognize that “there is a special ecumenical calling to which they have responded.” Nicely put—and well worth a ponder or two.

Author J. D. Douglas lives in Saint Andrews, Scotland. He is editor at large forChristianity Today.