One day last year in the middle of June, I was descending a trail leading from the lip of a rocky Wyoming ridge to the sagebrush flats in the canyon below. Quite suddenly a hawk dropped through the branches of the pines in a lazy, controlled parabola and, hanging at the nadir of its long arc for a moment, grasped a negligent ground squirrel in its claws and flew away among the trees again.

One stops at such sights. I stood in the thicket of limberpine for a good quarter of an hour while the import of this unexpected scene seeped through me.

Was the message of this secluded morality play I had stumbled into merely memento mori—a reminder of inevitable death? It had been played out with a certain ease and grace and matter-of-factness. The small rodent had not squealed or struggled. The only sound had been the sheerest shuffle of wind through the bird’s wings. It caused no more stir on the rocky slope than my sitting down to breakfast did in my house.

So this was death—from natural causes, as we say. Death descending from the sky on silent wings. Death with implacable, immobilizing talons. Death somewhere, not far away, ripping open the warm carcass while I still stood under the tree. The necessary death of this world. Death destroying in order to live.

I went on down the trail, descending the switchbacks and trying to keep my analogies under control. For I sometimes thought I heard wings overhead myself. There is the dove of heaven, we know, that descends when the heavens open, sometimes in fire. But perhaps there is also a hawk in heaven that swoops down on us with the gift of death to deliver us from our used-up past, the past we have neither the courage nor the imagination to walk away from.

We mortals die many deaths in our lives. Patterns that have served the purposes of their particular time and place have to be discarded and left behind. If we grow in wisdom and stature, it is only over the dead bodies of our former selves. One cannot begin to live a new life until the old one has adequately died. Otherwise, life itself becomes nothing but an artificial resuscitation, year after year, of a desiccated, worn-out self, a mummy with only the painted appearance of life.

Death In The Wilderness

The Wyoming wilderness, especially in winter, is an instructive place to learn about death, even to learn how to die. Here death is not covered over or whisked out of sight. It is difficult to learn about death today in towns, at least in respectable neighborhoods. No horse-drawn hearses clop by with mourners in their wake to remind the community of the inevitable. Those sick enough to die go to hospitals where machines monitor their descent into death. If city children no longer know where milk comes from, still less are they acquainted with the source of hamburger.

But in the wilderness things die in the open, nor is this indecent. In fact, when winter descends on the northern Rockies and grips the land in its obdurate talons, death becomes the daily diet of contemplation. Animal populations are thinned of their weak members. Vegetation sinks its capital into its deepest roots. And the wind scours even the stones of any detritus or extraneous life.

Not many people want to learn about dying. Maybe that is why the population is so sparse among the bare bony ridges of Wyoming. To be sure, we live in terrified times and our world is understandably more interested in images of reassurance and rebirth than it is in death. At each moment, death that could be the end of history waits to erupt from the underground Wyoming weapons silos, let loose by some hand over which we have no control. Children grow up under the shadow, not just of their own deaths or the deaths of those they love, but under the shadow of world death, future death.

Perhaps our terror of death at other hands is so great that we cannot concentrate on our own task of dying and instead try to leap over that abyss, attempting to be born again without dying first. If so, I don’t know that we are so very different from other ages. There have, in fact, been times in history when whole civilizations have been driven mad with death: fourteenth-century Europe and the Aztec kingdom, for example, when people wallowed in death in order to inure themselves to its terrors. Perhaps this is our own motive for watching people being killed over and over, artificially and not very accurately, on television. Perhaps this is our unconscious Aztecan ritual that accustoms us to the terror of death.

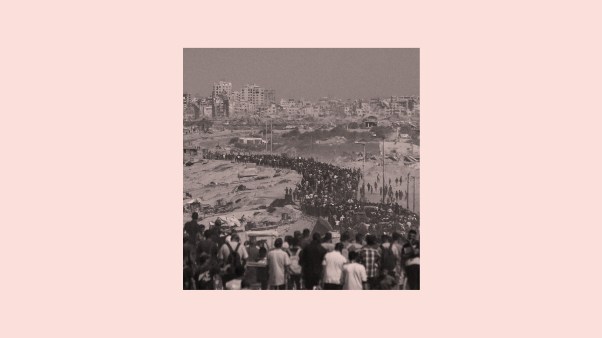

But we are not the first generation to live in a reign of terror, despite our technological weapons. Apocalypse has threatened—and happened—before. The world, as its inhabitants then knew it, has been destroyed before. Sodom and Gomorrah, incinerated and smoking on the plains, is only a scale model for our own fears about the future. The citizens of those cities knew not much more of the world than their own neighborhood. To them the fire and brimstone were, effectually, the end of the world. Holocaust is not new among humankind. Jericho, Jerusalem, Rome, Dresden, Hiroshima, Hue—all the world that somebody knew has gone up in flames before.

This is the death that is the enemy, the death that aims at the unmaking of creation. This is the enemy that desires creation’s diminution, its degradation. This is the death that would destroy the world if it could, either in one great conflagration or by sucking life slowly at whatever fissure it finds in the entities we call our bodies and souls.

But if death is only the enemy, how then do we dare speak of the necessity of death in our lives, of how we must die with Christ, be in fact baptized into his death? Why does the common table at the heart of our faith commemorate the very death of our Savior? Do we celebrate life or death when we consume body and blood?

And what, after all, is the nature of this death? Is it the necessarily opposing force to life that holds reality together as pictured in the light and dark of the yin-yang symbol? Is it only a part of the cyclical process of being? Do we protest against it only because our flesh, entangled in time, deludes us? Is death actually a release from the illusions of time and space and particularity? Is it rest? A sleep and a forgetting? Or is it punishment? The wages of sin? Should we desire it, as Paul did, as access to the presence of God? Or should we cry out against the dying of the light?

On Necessary Death

Certainly there is the death that, within the context of earthly existence, is necessary. If all beings were on earth immortal, where would food come from? Or time, for that matter? We know little enough about this kind of death and do not contemplate it sufficiently to understand our own creaturely nature.

And what is the meaning of that great lost word of the church, one it seldom utters now—our death in Christ? Why are we called upon to embrace this enemy? Why did not Jesus, like his Jewish kin, the Maccabees and the Essenes, build a fortress against the enemy where we could all huddle together in safety? Why did he, in order to “deliver them who through fear of death were all their lifetime subject to bondage,” invade the kingdom of death itself?

One must, it seems, close with the enemy in order to overcome it. Death could not be destroyed by keeping clear of it. A great reversal is always accomplished on the point, the fulcrum, of a paradox; an infinitesimal eye at the center of the storm we call human history, a place becalmed, transfixed, immobile. There light confronted darkness, consciousness looked into chaos, being met unbeing and was not overcome.

But we forget that we too are called to that place. We, too, find life only by losing it. In order to know the power of the Resurrection, Paul said that he must share Christ’s suffering, “becoming like him in his death.”

We, too, must learn to lay down our lives and walk away from them. No death therapy can help us here. Breaking down the process of dying by analysis into five or any other number of stages is insufficient to our needs. We play parlor games with the psyche in order to subdue reality. That may be entirely necessary. Even Aristotle described Greek drama as a useful tool for coping. But we must beware of thus diminishing our very selves and the unrepeatable experiences vouchsafed to us.

I know all life to come from God; I also know that the approach to the source of that life lies only through the valley of the shadow of death, our death in Christ. Death is that narrow, straight gate through which we struggle toward the light. There is no other way, and that way is so lean, so constricted, that it scrapes all the flesh from our skeletal selves before we can writhe and heave through the aperture. Who enters there leaves everything behind: brothers and sisters, mother and father, home, hope, fear, fancy. All the flesh is scraped off in that centrifugal force, the bones tumbled smooth as stones.

Annie Dillard asks, “Did you think before you were caught, that you needed, say, life? Do you think you will keep your life, or anything else you love? But no. Your needs are all met. But not as the world giveth.… You see the creatures die, and you know that you will die. And one day it occurs to you that you must not need life.” And Bonhoeffer, amid quite different circumstances and with the heightened awareness that war with this world brings, put the case more succinctly: “When Jesus calls a man, he bids him come and die.”

The Difficulty Of Voluntary Death

For human beings, the necessary death, the death essential to life, is always voluntary, which is what makes it so hard. The rest of creation, though it dies, has no need to make an act of the will. Death simply comes upon it and overshadows it, in the dive of the osprey, the pounce of the coyote, the freezing of cells.

Nevertheless, in everything but will, creation—dumb, brute creation—can show us something of how this dying is done. Indeed, how else can we know death except among the creatures?

Yet even our ties to earth-death are being systematically cut off. We neither kill nor harvest the food for our own tables. It comes to us already death-processed. We have no bone-deep knowledge that other things die so that we may eat and live. How can we then possibly sense the depth of sacrifice that atonement requires? Our salvation seems easy and grace cheap because we have lost the death link to our tables. Since we are deprived of death within our own dwellings, we must look elsewhere for instructive examples. Outside.

Outside, the world itself dies every year. We have almost forgotten that. The sun withdraws its light, the darkness overshadows the earth. The waters freeze and the leaves decay. We forget because we don’t have to live in that world anymore. We have created our own world where we have as much light and heat as we desire, hot running water, and fresh fruit the year round. We exempt ourselves from the season of death that envelopes the world outside our artificial environment. We live as though on an alien planet; this has become our imitation victory over death.

How is this kind of ignorance to be instructed? How can we learn what it is we mean when we use the word death? We have gotten woefully glib with our theological metaphors. We need either to change the metaphors to match our experience more honestly or else experience the metaphors we insist on using. We need to watch as life abandons the land in winter, to contemplate in detail the dereliction of creation. Then maybe those mute lessons will seep slowly into the landscape of our minds so that we can learn to bear the abandonment of our own lives.

Tim Stafford is a free-lance writer living in Santa Rosa, California. He is a distinguished contributor to several magazines. His latest book is Do You Sometimes Feel Like a Nobody? (Zondervan, 1980).